I can still recall the fateful night of Aug.15, 2021 as if it was yesterday.

Afghanistan fell into the Taliban’s hands. Heartbroken and perplexed, I was tweeting about the Taliban’s entrance into the presidential palace from an unknown location. I had fled my own house in the middle of night when the Taliban were at Kabul’s gate. The fright and distress was valid; in the past, the Taliban had killed numerous journalists, activists, government employees, and those who criticized their acts on social media. I, too, was a social media activist, journalist, government employee working with the state broadcaster, and above all, a well-known critic of the Taliban.

I knew the bell had rung for us and sooner or later we would be captured by the Taliban and tormented for our freedom of speech. In the newly conquered provinces, Taliban fighters were conducting door-to-door searches, executing people, specifically those who had collaborated with any Western or Afghanistan’s government. Our — the critics — chances for survival were close to zero now.

I stayed up the whole night, thinking about the upcoming days and our ill fate. I had deactivated my phone’s SIM card, and WiFi was the only refuge to stay connected with my loved ones. Friends and relatives from abroad and Afghanistan started inquiring about my wellbeing and whereabouts, but I left many of their messages unread and unanswered. The reality was that I didn’t know how to respond.

Forty-eight hours had passed with no sleep and a lost appetite. My parents’ distress was apparent. They were worried about my wellbeing, as they had seen many parents bury their young sons — sons who have been killed by the Taliban or targeted in suicide attacks. I didn’t want my parents and family to suffer further because of me, and decided to knock on every door in search of help.

FLEEING FOR OUR LIVES

I began contacting all the international organizations and foreign embassies around Afghanistan. I had good relations with ambassadors of many countries with whom I had conducted interviews for our channel, but at my worst hour, I realized that none of them were actually friends. Most of them either ignored my messages and left them unseen and unread. This shattered my last hope for survival. I felt as if the entire international community had betrayed us and thrown us to the mercy of wolves. There was no one to share our grief or hear our plea.

Since arriving in Melbourne, I’m still processing the events that occurred back in Afghanistan. If you ask me, I’m still in a state of trauma. Every morning I wake up and think it’s a dream, but then with the passing day I realize that this is my new reality.

I mailed all the relevant journalist protection organizations too, but soon realized I wasn’t going to get any help from them either. As a last attempt at seeking refuge, I wrote a plea for help to the international community in the form of a letter. Unexpectedly my prayers were heard and a senior official of the Australian government asked me to send her my contact number and email. I immediately replied with my WhatsApp and received a text message from her stating: “Hi Khalid, don’t worry I am here to help you. Share your details.” I sent her my family details, including passports and IDs, while still doubting that she would actually help. I was awaiting the very familiar “we are sorry” message that I had received from all prior contacts. They all used to start with “Khalid that’s quite unfortunate, I do understand what you guys are passing through, but I am not sure if I can help.”

Yet, this time it was different.

I could hear a tone of assurance — and empathy. The Australian official gave me hope once again and told me to wait for her response as she tried her best to arrange my safe evacuation.

The very next morning, I got a call from that same Australian number and it was the familiar voice of Minister and Senator Linda Reynolds. I couldn’t believe my ears as she gave the most awaited news of our evacuation. She informed me that the Australian government had granted visas to me and my family. I was stupefied and still couldn’t process that this was actually happening. With tears of bliss in my eyes I rang up my parents and informed them of our departure.

Getting to the Kabul airport was now the main challenge. The senator had spoken to French officials to arrange a conveyance for us from Serena Kabul to the airport, but that didn’t work out as Taliban were at the gates of Serena Hotel and not allowing anyone to enter the premises. As we waited for the car, a Taliban guard had a harsh conversation with my father. The Taliban guard called my father a coward for taking his family to the lands of impure where they’ll all be converted to infidels, and that he deserves to be killed. He even told my father that if it was possible, he would gladly kill him right there.

After facing much resistance, we finally made it to the airport, where thousands of people were already stranded, desperately trying to reach the gates and board a plane to escape Afghanistan. I could hear gun fires, people jumping and running over women and children, some climbing and clinging to the aircrafts taking off, and plummeting to their death thousands of feet below.

It was a chaotic atmosphere filled with frenzy and despair. There was tear gas and heavy gun firing going on. My mother fainted twice while my baby sister was petrified. We had no food with us, but luckily managed to buy a few bottles of water from some local vendors.

After spending two nights outside the airport gate, we finally made our way near the coalition forces. There was a one meter long drainage water between me and the coalition forces soldiers who were checking visas, but I didn’t think twice before jumping into it. I wasn’t alone, hundreds of families holding visas and other documentations in hand were there, awaiting approval.

It was eleven o’clock at night when I was able to show the coalition force soldier my visa papers printed in A4 size, which he rejected, stating very curtly that they are no longer accepting visas on paper as those could be fraudulent. He further told me that for now they are only letting US nationals or other western country passport holders leave, and no one else. I was in contact with Ms Reynold via Whatsapp and immediately notified her regarding the situation. She called me and asked to speak to the soldier. After speaking to her for a minute he let us through, and we were taken to the Australian military base. The moment we stepped inside the base, I breathed a sigh of relief, for now we were in safe hands.

We were under open sky with other refugee families and their luggage from 11am till about 3am the next morning when we finally boarded a military flight that took us to Dubai. We spent eight days in a camp. Looking up at the sky, I felt relieved to be safe, but guilty for leaving behind so many friends and colleagues. I felt as if I had failed the people and my country who were left behind helpless. I could recall the last time I had been through that airport, wearing a new suit and a big smile. Whereas, now all I had now was a bag with my laptop, a spare pair of jeans, and an extra T-shirt.

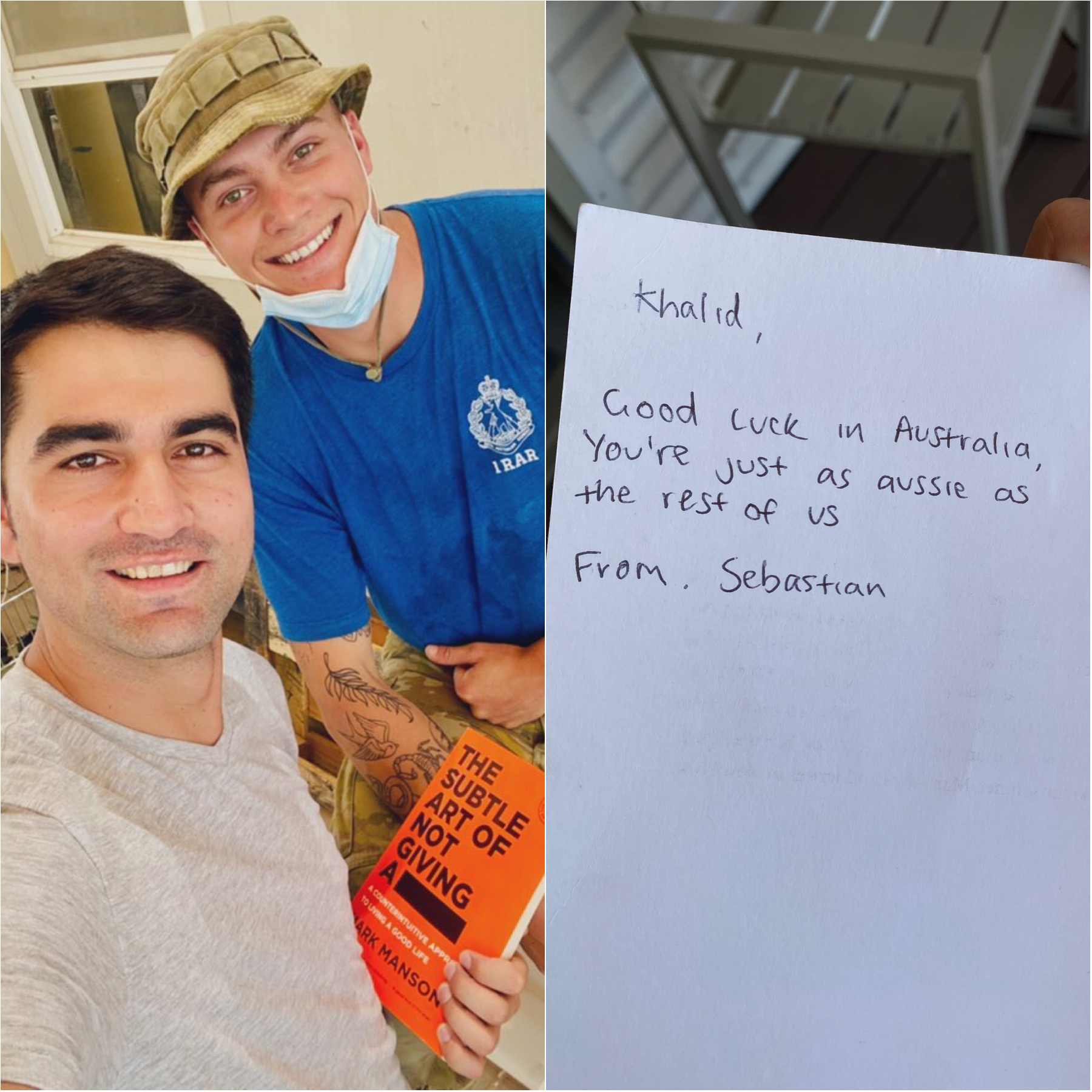

During my time in Dubai, I struck up a conversation with an Australian soldier. He asked me what I was reading. In response I told him that I didn’t have anything to read, but that I was keen to get hold of a book called “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck” which is about how to live a good and happy life when things don’t always go well.

He returned a few days later with a copy of the book and a handwritten note in it which read, “Welcome to Australia. You are just as much an Aussie as the rest of us.”

This courteous gesture and his words warmed my heart.