Pundits assumed the man who would fundamentally restructure US-Mexican trade was Donald Trump. In the coming year, that role may be unwittingly filled by an accidental protagonist: Emilio Lozoya. This past August, Lozoya — the former head of Mexico’s state-owned oil company PEMEX — revealed explosive allegations of corruption within the country’s oil sector. Among them, he admitted to buying several Mexican lawmakers’ votes ahead of a contentious 2013 vote to open the country’s oil sector to foreign investment.

Thus far, analysis of the case has focused on the Mexican president’s schadenfreude in response to his political rivals’ involvement. Yet Lozoya’s implications reverberate far beyond Mexico. If pursued by the Mexican judiciary, the vote-buying allegations have the potential to destabilize the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). A treaty breach, a partial annulment or a renegotiation of the agreement would further harm all three signatories’ economies during an already tumultuous fiscal year.

Mexico’s complex relationship between politics and oil reveals why buying votes to ensure liberalization was so consequential. At the turn of the 20th century, when Mexico’s vast reserves were first discovered, international companies flocked to extract oil for low prices and undercompensate the Mexican government. Mexican citizens did not reap the benefits of oil wealth and were denied social safety nets while experiencing political repression. In the 1930s, as Mexican politics swung to the left, the oil sector was nationalized, and its revenue fueled social service provision for the country’s most vulnerable. Nationalized oil with high barriers to foreign entry — a source of national pride and sign of economic sovereignty — remained Mexico’s status quo until the 21st century, despite NAFTA negotiators’ pressure in 1992 to modify it.

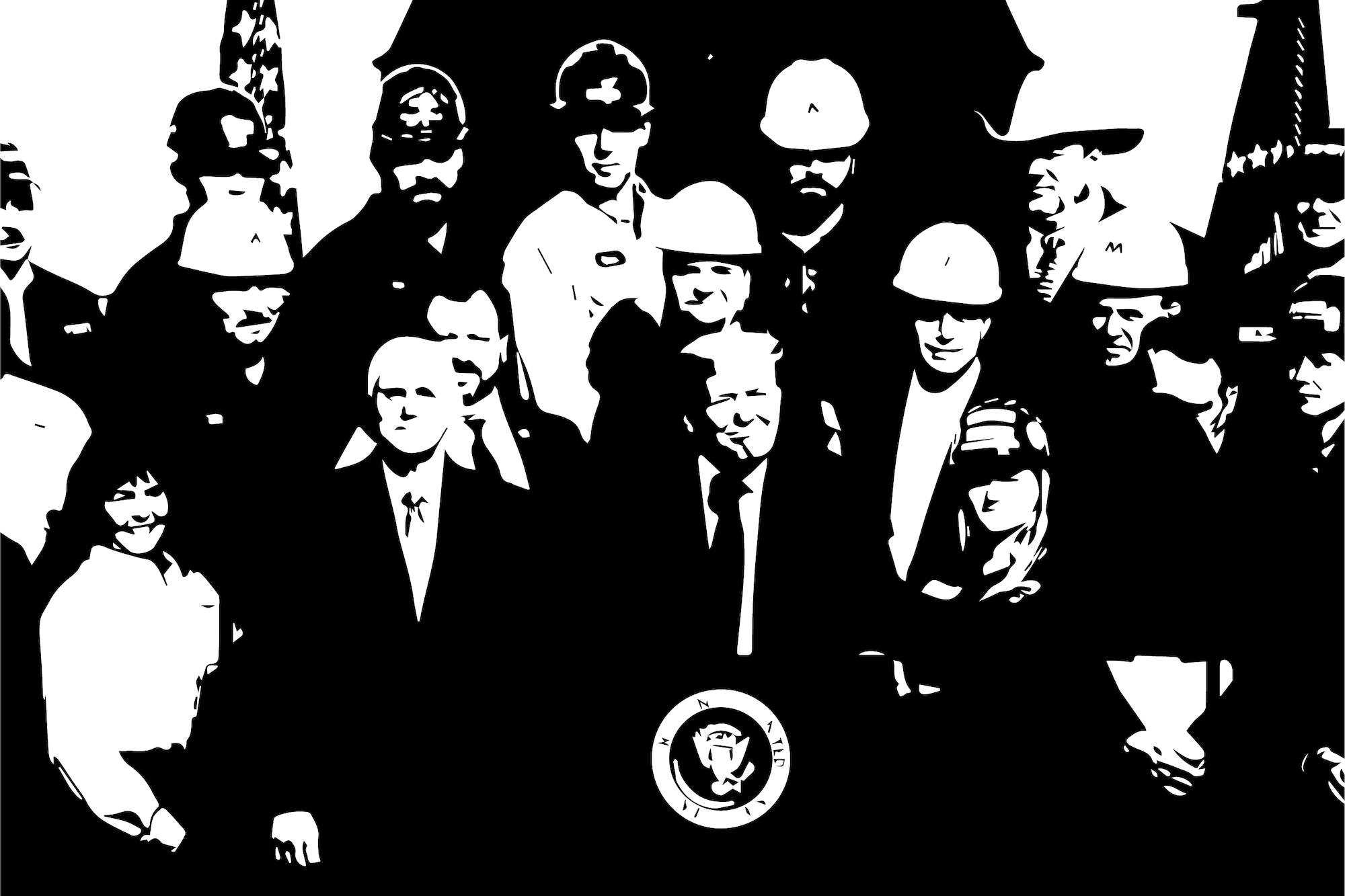

Given this context, the 2013 Mexican congressional vote to open the oil sector to foreign investment was pivotal. The reforms were spurred by Mexico’s declining competitiveness among global oil producers and PEMEX’s dwindling funds. They gave international oil companies “exploration and production rights in both onshore and offshore blocks in Mexico.” Partisans in favor and against liberalization relentlessly vilified each other, with anti-liberalization advocates calling liberalization “a betrayal of the nation.” Despite high-running public sentiment on both sides, the final vote was a lopsided 353-134. Seven years later, the 2013 liberalization became the conceptual cornerstone on which Article 32.11 of the USMCA rests.

With Lozoya’s allegations, the murky process behind the acrimonious and seemingly too-good-to-be-true 2013 vote has come to light. Given that liberalization of the oil sector was achieved through illegal methods, the law may be overturned. If policies of liberalization are undone, Article 32.11 of the USMCA would no longer be enforceable. This would be near-disastrous for US energy companies operating in Mexico, which thus far have been well-represented among the 60-odd companies awarded contracts. With one of America’s most salient business sectors in the USMCA forced to rethink its options, the US economy would inevitably feel an impact.

Of course, this projected domino effect depends on how proactive and independent the Mexican judiciary may be on the issue. Mexico is currently facing an economic crisis coupled with civil society protests denouncing violence against women. The link between Lozoya and the USMCA is likely not the top judicial priority. Additionally, the Mexican judiciary has long suffered from allegations of non-independence and institutional weakness. Whether it has the capacity to bring charges against Lozoya, corrupt congressmen, or revoke the 2013 law is unclear.

Nonetheless, two factors make it likely that the Lozoya-USMCA link and subsequent issues will not disappear. First, Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador recently proposed — and Mexico’s Supreme Court approved — a public referendum on whether past presidents should be investigated and prosecuted for corruption. Among the proposed referendum topics is a deeper examination of the bribes related to the 2013 oil reform. Secondly, the Mexican judiciary’s institutional weakness could change over time. In recent years, some Latin American judiciaries have gotten stronger after corruption scandals, as was the case with Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court and the Operation Car Wash scandal.

Regardless of the Mexican government’s next actions, one lesson for US policymakers is clear. It is crucial to analyze the domestic processes that lead allies to sign international treaties, particularly if the terms are strikingly favorable to US interests. Failure to question diplomatic “good results” out of convenience breaks an American tradition of promoting transparent, ethical governance at home and abroad. Complacency ultimately harms American economic interests too, as evidenced by oil companies’ potential lost revenue if the USMCA is modified or annulled. As illustrated by Lozoya’s testimony: the smoother the process, the more well-oiled the problems.

Isabel Bernhard (@isabernhd) is an MSc. candidate in Latin American Studies at the University of Oxford.