Recent attention to large numbers of migrants, including unaccompanied minors, arriving at the border has inspired anti-immigrant activists and politicians to broadly criticize the Biden administration’s proposal for comprehensive immigration reform. However, the proposed legislation that has been introduced to both the House and the Senate addresses two very different populations of migrants, whose distinct circumstances should be considered separately: those who are to be or have been deported and those who are seeking asylum.

The Humanizing Deportation Project, which I designed and have coordinated since its launch in 2016, has documented the personal stories of over 250 migrants, including both those deported from the United States, and those in process of migrating along the Central America–Mexico–United States corridor. Their stories help illuminate the issues at hand.

ISSUE ONE: DEPORTATION

The first issue that must urgently be addressed is the lack of a humane approach to the many undocumented immigrants who have lived long term in the United States. Currently these immigrants are subject to deportation at any moment, often causing long-term family separation, or breaking up families entirely. It is nearly impossible to introduce family hardship as a mitigating factor in deportation cases, which generally assign penalty periods of ten years or more during which deported migrants are ineligible to apply for any type of visa to enter the United States.

No other country in the world has been as aggressive or harsh in its treatment of such large numbers of long-term undocumented immigrants as the United States, which routinely expels hundreds of thousands per year. For example, the European Union, which also expels significant quantities of undocumented migrants, focuses much of its attention on asylum seekers whose applications have recently been rejected, with “regularization” programs available to some longer-term migrants. EU member states also use discretionary power in those cases in which deportation would imply human rights issues.

No other country in the world except the United States has been as unrelenting in breaking up families, nor has any other nation maintained such large numbers of childhood arrivals in the precarious position that is faced by hundreds of thousands of adult immigrants. Karla Estrada tearfully describes the arrival of her younger brother, who, like her, was brought to the United States as an infant, upon his deportation to Mexico: “He did not know what it meant to be in that country, he did not know how to appropriately speak the language, or dress, or anything of the culture of Mexico.” In order to protect him, her undocumented parents decided to return to Mexico, leaving Karla, a University of California, Los Angeles grad and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient, alone. As she puts it: “I still can’t find the words to describe how much it hurts to lose my family so fast; it feels like, like is a slow deep wound inside you that never quite heals,” adding that “very rarely we talk about the effects of deportation, not only for the deportees and veterans, but also the families left behind in the US. It is a pain that I don’t wish upon anyone, not even in my worst enemy.”

Nor has any other nation been as unforgiving of its noncitizen military veterans, who routinely get deported from the United States for committing criminal offenses, including some minor drug offenses. US Navy veteran Alex Murillo was brought to the United States at age one, and obtained legal permanent residency. He served respectfully and proudly in the US military and was stationed in the Middle East. After his discharge he lost his way, ending up convicted in federal court of marijuana charge, which automatically triggered his deportation. He left behind four young children, who, he recalls, “were waiting for me and I never made it back home.” Neither Alex nor his family can understand why he was “good enough to fight and die for America, but I’m not good enough to live there.”

The effects of the United States’ heavy reliance on deportation have been devastating to immigrant communities. With an aim to keeping families together, the Biden immigration reform proposal offers many long term immigrants, including childhood arrivals, a path to citizenship, and also gives discretionary power to immigration judges and new authority to the Secretary of Homeland Security and Attorney General to take the hardship that deportation would cause to families in consideration, allowing them to both block deportations of migrants who pose no security risk, and to facilitate the readmission of previously deported family members. The past 25 years have seen a relentless assault on immigrant communities, which has become only more and more severe. It is time that we take a more humane approach with long-term undocumented immigrants.

ISSUE TWO: THE MIGRANTS AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

The question of migrants arriving at the border is a separate one, perhaps a bit more complicated. The majority of these migrants come from the northern triangle of Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) and aim to seek asylum in the United States. The situation at the border is unfortunate, the culmination of several years of efforts to deter these migrants’ ability to complete or, more recently, even initiate the asylum application process. The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program, launched in January of 2019 has kept tens of thousands of migrants on the Mexican side of the border awaiting court dates in the United States, while the Title 42 “express deportation” procedure has expelled nearly all asylum seekers that have tried to cross into the United States since March 2020, under the premise of safeguarding public health during the pandemic. This decision was revised recently to allow unaccompanied minors and some families with children into the country.

The Biden proposal promises to address the problem at its root by offering aid to northern triangle countries to help them assure the economic stability and personal safety of their citizens so as to prevent them from departing in large numbers. This is obviously a long-term solution. In the short term, given both the now huge backlog of asylum seekers due to MPP and Title 42, as well as the steady arrival of new asylum seekers, it is urgent for the United States and Mexico to coordinate logistics and offer basic protections, such as safe lodging for migrants, on both sides of the border.

Another underlying issue is especially troubling: that of refugees. The migrants who have spoken to scholars and the press represent themselves as refugees — who are migrating not on a whim, but rather out of desperation. It is logical that refugees seek asylum. But US asylum law requires applicants to demonstrate that they are being persecuted based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Threats of violence from organized criminal groups do not necessarily align with these criteria. This is one of several reasons why the rate of success of asylum cases for Central American migrants is very low — and falling.

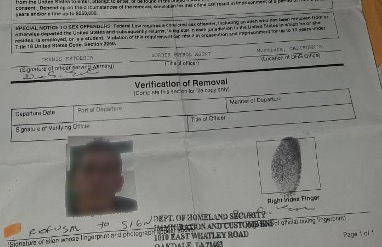

For example, a Honduran migrant who traveled with the 2018 caravans had to close his auto repair shop when he was unable to pay extortion demands from criminal gangs. He was also witness to a kidnapping and agreed to testify for the state, assuming he would be protected. He was instead required to testify in front of the accused and eventually convicted defendant, then denied any form of government protection. He fled Honduras in fear. Upon crossing to the United States to apply for asylum, he was questioned by Customs and Border Protection agents who allowed him to tell only the first part of his story. They refused to let him file an asylum case, and ordered him to sign a voluntary removal form. When he refused to sign, he recalls: “they insulted me, they told me that I looked like a delinquent.” They then screamed obscenities in his face and “got rough with me.” Three agents “grabbed my hands and bent me backwards,” forcing him to put a fingerprint onto the form, which they then used to deport him.

While in 2016–2017, asylum was granted to roughly 25% of applicants from all three northern triangle nations (compared to about 40% among all applicants worldwide), by 2019–2020, success rates of northern triangle applicants had dropped to below 15% (versus an aggregate rate for all applicants of about 28%), with 91% of MPP cases ending in deportation. In other words, even though these migrants see themselves as refugees, US immigration courts infrequently see them as refugees.

While it is important to address the problem at its root by improving living conditions for Central Americans, and to offer humane and secure conditions for asylum seekers at the border, it will also be important to better align expectations with reality. Either the United States must revise its criteria of evaluation for asylum cases in order to better account for real dangers of extortion, assault, kidnapping, rape and murder to which so many of these migrants are exposed in their home countries, or Central American migrants, who often risk life savings and face all kinds of dangers on the migrant trail, should be better informed of what lies ahead once they reach the US border, as currently the vast majority of them are ending up getting deported back to their countries of origin.

It is clear that more humane legislation is needed for both long-term immigrants and newly arriving asylum seekers. Given the very different challenges each group faces, it makes sense to consider them separately.

Robert McKee Irwin is the deputy director of the Global Migration Center at the University of California, Davis.

The images that appear in the body of this piece are from the Humanizing Deportation Project.