A friend from college called me the other day. We chat from time to time about family and life, but yesterday he sounded serious: “I don’t really follow the news, and things sound bad,” he said. “Is Putin going to start a nuclear war?”

Having a friend who works on nuclear weapons and deterrence, I guess, is a novelty. And as much as I wanted to tell him everything would be fine, and he had nothing to worry about, I couldn’t. The reality is that the world was already dangerous. Today it is even more so because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and President Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons against any who would stand in his way. And at the same time, those who work on nuclear issues know that the world has grown numb to the risk of nuclear use. Despite the end of the Soviet Union 20 years ago and a prolonged period of peace and prosperity for many, both the US and Russia have retained the explicit right to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict. Both have maintained thousands of nuclear weapons deployed and ready for use on both sides, meaning that nuclear weapons could have been used without much notice or warning. Both spend billions on these weapons to boot; America $50 billion per year to modernize these forces they hope will never be used.

I did what I could to reassure my friend. I explained that Putin was unlikely to use nuclear weapons because he knows that America could respond with nuclear weapons of his own, ending whatever dreams he has for both power and legacy. He might be brutal, but not irrational. At the same time, I told him people screw up. In the fog of war, when countries and even small groups like ANONYMOUS can take down communication networks, when planes can bump into each other, or soldiers shoot not knowing what they might hit, things can get out of control quickly. As much as I wanted to tell him there was a room with really smart people who could and would prevent the worst from happening, the reality is I had been in all of the rooms and there was not such a perfect place.

As much as I wanted to tell him there was a room with really smart people who could and would prevent the worst from happening, the reality is I had been in all of the rooms and there was not such a perfect place.

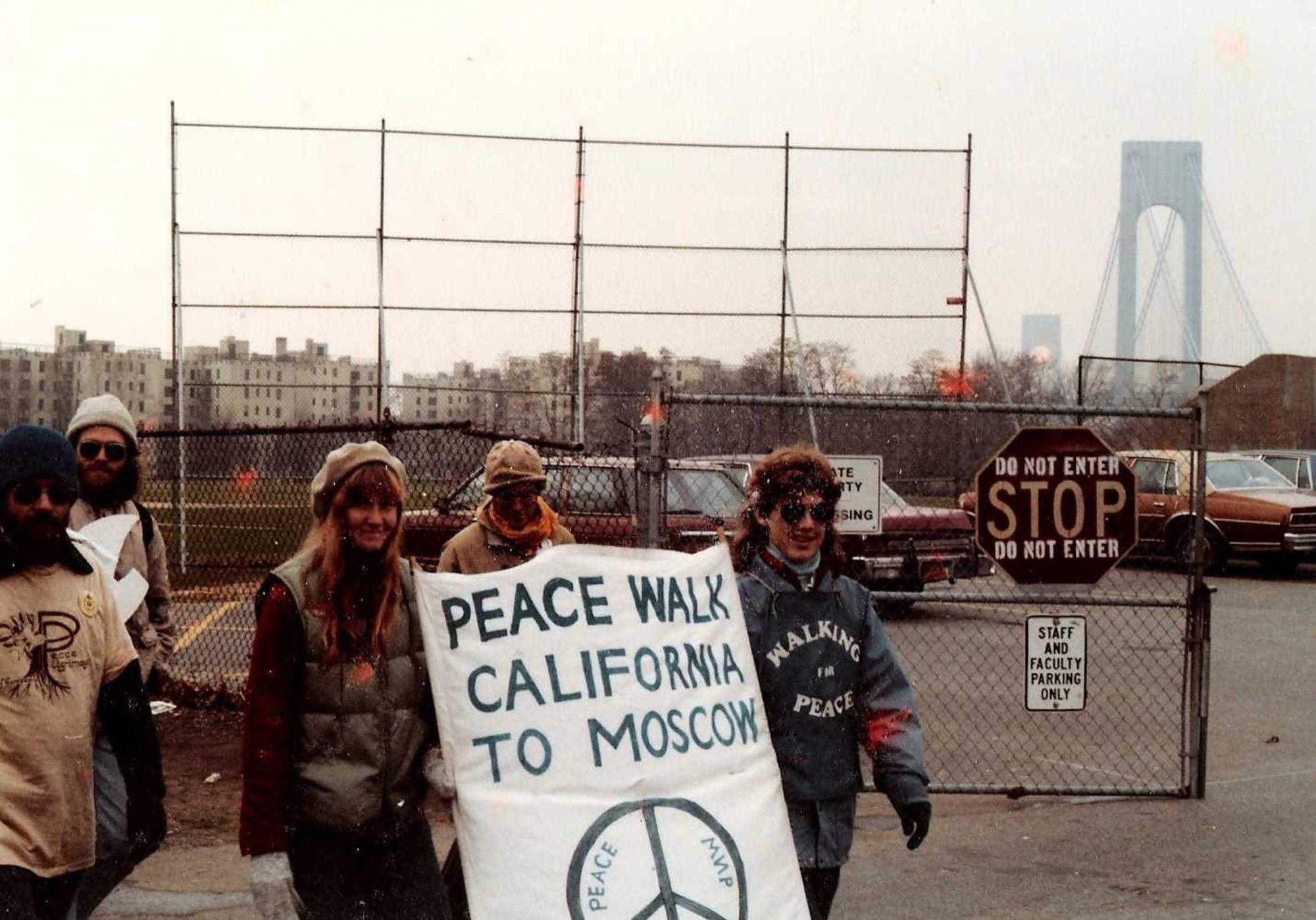

But then I reminded him we grew up like this. When we were kids in the 1970s, American and NATO troops on one side and Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops on the other stared each other down in a daily ritual that often risked war. Of course, they screwed up and had close calls, but over time got a little better at signaling and communicating and avoiding the worst. And while we thought we had left those dark, dangerous times behind we lamented that we were going to have to help our kids navigate a similar set of concerns.

These are dangerous times. Russia has a large and very usable nuclear arsenal and is now using those weapons as a shield to carry out its invasion and subjugation of Ukraine, a sovereign European state. But even before that, we were living in a dangerous time — we just ignored this fact. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists doomsday clock (which I help set up) has been stuck at 100 seconds to midnight for three years — the closest to disaster it has ever been. Having survived four years of impulsive, and often irrational, behavior by a US president with full and complete control over 4,000 nuclear weapons, the clock setters now find ourselves confronted with a man who uses his nuclear arsenal as a shield, behind which he literally seeks to undermine the basis for sovereignty and stability in Europe by carving up Ukraine.

There are some things that make today safer than the Cold War standoff, but others that make it worse. Today, we communicate with Russians instantaneously. They know where we are, and we know where they are. Satellites, computers and other technology can help us know what is taking place where. These are tools that have proven their worth at conflict and risk management. If all sides truly want to avoid a conflict and end a war, they can do so much more quickly than in the past. Sadly, this is not Russia’s current approach, with Putin instead seeking to weaponize risk instead of manage and reduce it.

At the same time, we see playing out on social media and in real life (remember not to confuse the two) the other sharp side of that same blade. Rumors travel faster than fact. Photos of explosions attributed to Russia today might be from Syria five years ago. Allegations on both sides are made not to inform the forces of moderation, but to justify their own actions and paint the other in the worst possible light. And under the surface, cyberattacks and military actions can quickly degrade our ability and that of Russia to know what is actually taking place. These actions can come from Washington, Moscow, Kyiv, or even as far away as Pyongyang. Anyone with an interest in amping up the crisis or shaping it to its own ends can today interfere in the battlespace with unpredictable results.

That is why I have been reassured by President Joe Biden’s clear statements that he seeks to avoid a direct conflict between American and Russian troops in Ukraine. He, more than perhaps any president since Dwight Eisenhower, understands the history of this conflict and the subtleties of nuclear deterrence. But even the best intentions of one side cannot ensure that the interests of all to prevent nuclear use win out. The only thing that can ultimately prevent the use of nuclear weapons is their removal from the battlefield and, eventually, with strict verification, their removal from the arsenals of all countries.

Until then, I expect to keep fielding calls from old friends who want to share old stories and then ask, “Are we going to be ok?”

Jon B. Wolfsthal is senior advisor at Global Zero and former Special Assistant to the President. He served as Senior Director for Nonproliferation and Arms Control on the National Security Council and is a member of the Science and Security Board at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.