This was similar to what we heard nights later from a young Naval officer. We were at the bowling alley food court for dinner and decided to chat with the person behind us in line. Like the high schooler, this 20-year old also said there wasn’t much else to do on the base, and nobody talks or thinks about the detention center. When asked about his reaction when he found out he was to be stationed there for 2–3 years, he said the name sounded familiar, but he didn’t know why and Googled it.

This caught us a bit off guard. The so-called “War on Terror” has spanned his entire life, as has indefinite detention at Guantánamo. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the United States became a fear-based, hyper-nationalist security state. So it surprised me that a younger person who joined the military was unaware of where he was going. But perhaps I also understand.

On the days we weren’t in court, we were encouraged to explore the island. My response to that was I really can’t explore it because I am told where I can and cannot go.

I also largely grew up in the post-9/11 era. I wasn’t taught in school about “special registration” for Muslims, torture, or Guantánamo, which is rarely the subject of mainstream press. I suppose there’s a logic to that: the United States doesn’t have much incentive for transparency, having chosen to operate outside of both domestic and international law, arrogant as well as firm in those choices. And in the 20+ years since there’s been no meaningful accountability for the crimes the United States committed.

The more we spoke to “locals,” the more we had to remind ourselves of why we were there. I remember having a conversation and wondering to myself if we were the irrational ones who thought something was wrong. Because the handful of restaurants, recreational areas, and one hypermarket exist on or are connected to the one main road, even though we landed Saturday afternoon, by Sunday night it felt like we were there for 3–4 days. Time had stopped, and the day seemed to persist. And attending court on Monday did not help.

TIME AND SPACE INTERRUPTED

After two security checks, we walked into a nondescript building, surrounded by razor wire, that houses the military commission courtroom. It was exceptionally cold inside.

We took our assigned seats in the gallery at the back. On one side were the NGOs and media, and on the other were the victims and family members, separated from us by a curtain. A member of the army read out rules for decorum and signs were placed on the walls which said, “No binoculars or other visual enhancement devices.” “No Google Glasses.” And “No drawing, sketching, doodling, etc.” Soundproof glass separated the gallery from the courtroom. So, while we could see what was happening in the courtroom in real-time, we could only hear it through the speakers running on a 40-second delay. The delay is to ensure that if any classified information is disclosed in the open session, the feed would be paused for the public.

This only worsened the time warp and distortion of reality. For example, the judge would walk in, and we would all rise; then we would see him, and the rest of the court members, take their seats in front of us through the window, so we would sit as well. But 40 seconds later we would see him again enter the room on the monitor and hear him say “please be seated.” Real-time rewind and press play, but for hours. I realized how agonizingly long 40 seconds is. At court, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the accused mastermind of the USS Cole bombing, was present. I remembered reading that in the May 2022 hearings, James Mitchell, one of the architects of the CIA torture program, testified about waterboarding Nashiri through 40-second pours.

Unlike the others we met, Nashiri is one of Guantánamo’s “residents” who cannot separate life from the detention center. He has been held there for 16 years. Captured in 2002, Nashiri spent almost four years being tortured in different black sites around the world before he was brought to Guantánamo in 2006. Videotapes of his torture have been destroyed. His case, in which he is facing the death penalty, is now in its 11th year of pretrial hearings with no trial date set.

A core issue being litigated is to what extent the government can admit evidence obtained by torture. Using such evidence is prohibited under domestic and international law, but in many ways, the Military Commissions were intended to play by different rules. I watched the prosecution try to build the case that Nashiri was no longer affected by four years of systematic physical and psychological torture when — not long after arriving at Guantánamo, and notwithstanding that he hadn’t (and still hasn’t) received any treatment for his torture — he was interrogated by officials from the same government who tortured him, at one of the same locations where he was tortured. The argument would be laughable if it weren’t so disturbing. It was one thing to know that the commissions were a failure and a sham by reading about them. It was another to witness the proceedings and hear the discussion.

In court, Nashiri was in a suit, clean-shaven, handcuff and shackle-free, where he sat with his defense team. At first, we didn’t realize it was him. We probably expected him to be what we have been conditioned to believe a detainee looks like — dehumanized to the point that we must do a second take and actively remind ourselves that they indeed are human. Dr. Sondra Crosby told me not to be fooled by Nashiri’s appearance, that wearing regular clothes such as the suit gives him dignity and agency, but he is still suffering deeply.

Over the last year, I have worked intensively on closing the Guantánamo detention center. I’m intimately familiar with its history and follow closely what’s happening there now. After a week-long visit, I can say that Guantánamo is a place I was not prepared for.

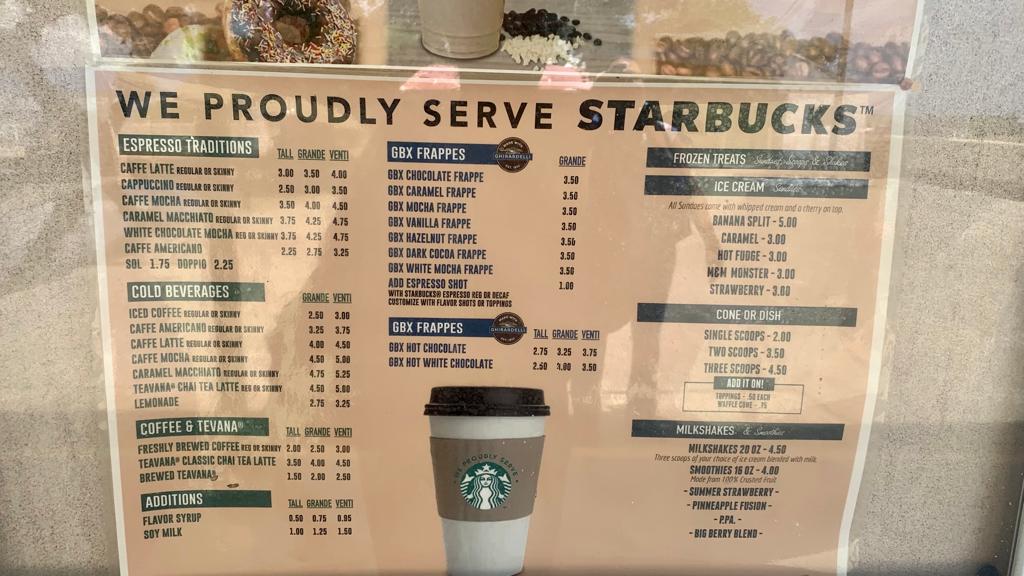

I caught some time with Crosby, Associate Professor of Medicine and Public Health at Boston University’s Center for Health Law, Ethics, and Human Rights and one of the first doctors allowed to travel to Guantánamo to independently examine detainees, at the Gourmet Bean — the only coffee shop on base and where one can find Starbucks products (seriously, it’s the Starbucks menu with Starbucks cups and ingredients, etc.) and Wi-Fi, besides the library.

We spoke about the impact of torture. When it’s done in such an extreme way, it becomes a part of the person and who they are. Many Guantánamo detainees experienced extreme torture and were conditioned in part by a technique called “learned helplessness.” Essentially, creating such an adverse environment where the detainees lose the sense of control or predictability. No matter what they did, the outcome would always be negative to get them to divulge secrets. And while through individualized, multi-disciplinary healing, survivors can live productive lives with new and happy memories, they will never go back to who they once were.

Though conditions at the detention camp have changed, indefinite detention is still cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. And the way detainees are brought from the camp to the court, they are retraumatized every single trip. During the proceedings, Nashiri asked to be excused because he was not feeling well. The journey takes a toll on him. There is no medical staff with experience in working with torture survivors and the defense is not allowed to bring in independent psychologists or psychiatrists to support him.

I asked Crosby what justice means for the detainees, why there is a lack of emphasis on the right to rehabilitation in international advocacy, and even the motivations of those who designed the CIA torture program; pausing mid-sentence multiple times when the frappe blender switched on, we joked our meeting was purposefully being sabotaged.

Though conditions at the detention camp have changed, indefinite detention is still cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. And the way detainees are brought from the camp to the court, they are retraumatized every single trip.

I wondered how someone in Nashiri’s position must feel when it comes to trusting people. He has endured severe torture and multiple people have come in and out of his life, including lawyers. When we saw him in court, he was happy to see his defense team. They all smiled, exchanged hugs, and it was obvious that he interacts with them outside of court. For one member of his defense team, building trust meant picking up their life from Miami and moving to Washington DC to show Nashiri commitment to his case. “He wants a connection, relationships, humanity. He wants his own humanity recognized,” the lawyer told me.

At Rick’s Officer Lounge in the Bayview Restaurant, we met the defense team. Rather than let them relax on their time off, we spoke to them about court, the witness testimonies, and asked them more questions. The rules of the Military Commissions are not those of the federal court system or even the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Since the government cherry-picked and made the rules, they get to win.

The deck is stacked against the defense. For example, the defense is not allowed to see all the evidence, and meetings with their client are circumscribed and limited in scope as to what the client can and cannot say. “The US has forfeited its right to try him. How is this fair?” one of the lawyers said. I asked about the role of international law in court arguments since the United States has long claimed itself to be the standard bearer of international human rights. Though if the US Constitution doesn’t play a role in Guantánamo, what made me think international law would have a shot? The answer was what I knew but didn’t want to be real, that “international law doesn’t exist as a body of law in America. It gets ignored.” They added, “We should be the last ones abandoning it, we built that apparatus.” Another said that “America cannot continue to claim moral authority if we do what we do here.”

DESTINATION FOR MIGRANT WORKERS

On the days we weren’t in court, we were encouraged to explore the island. My response to that was I really can’t explore it because I am told where I can and cannot go. I am told where and of what I can and cannot take pictures. Military personnel are authorized to use deadly force and to take our phones/cameras to delete pictures and not return our devices. But we explored nonetheless, as much as we could, driving past palm trees with views of the water at almost every turn.

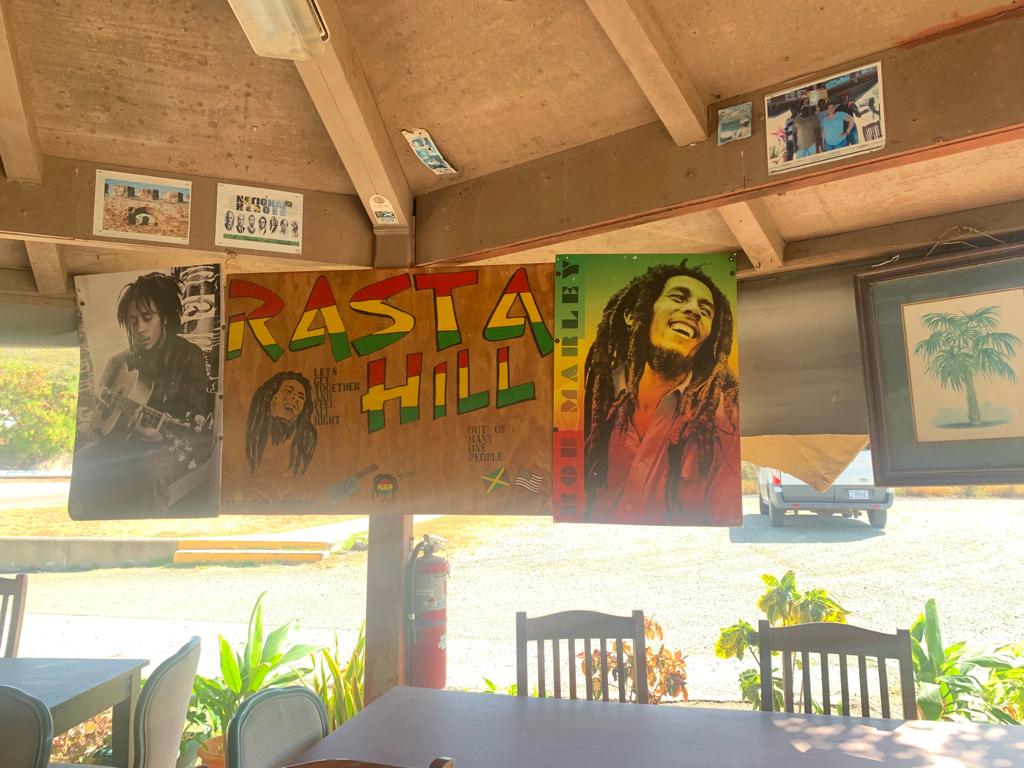

One thing we were surprised by was that at every single restaurant and store were Filipino, Jamaican, and East African migrant workers. I made the mistake of asking if we were allowed to speak with them. The media cannot interview them but there are no rules like that for NGOs. Yet, I was asked “why,” multiple times from different people, not thinking that would raise any sort of flags.

A few years ago, it was reported that migrant workers are paid somewhere between $1.50–$3.50 an hour. Perhaps that’s why the media isn’t allowed to speak to them. I also came across other information that gave insight into their lives and living conditions which made me understand why communication was discouraged. Allegedly, migrant workers are discouraged from dating and getting married on the base, as having a child would raise issues about the citizenship of the child. Would the child be American? Cuban? Both? Additionally, I was told migrant workers live in trailer prefabricated homes with two rooms and a bathroom. There is also an apartment building thought to house them with two bathrooms per floor. It was also alleged that Jamaican migrant workers are able to apply for and/or gain US citizenship after 20 years.

We spoke to a Filipino migrant worker one night briefly who told us he has been in Guantánamo for 18 years. He goes home almost every two years for two months.

A MORBID TOURIST SITE

We visited the museum and lighthouse to learn about the history of the island. We saw the remains of the infamous Camp X-Ray, which is now just a few thin fences and corrugated metal roofs with no other structure. One cannot tell there was anything ever built there, it looks like if there ever was a structure, it existed decades ago. It was barren, deserted, and surrounded by hills. There we talked about Abu Zubaydah, the famous “forever prisoner,” and pictures of the first prisoners brought to the prison that were recently released. We went to the top of a hill passing a sign that said, “NO photography/video beyond this point.” From one side we saw the whole base, and from the other the hills, ocean, and the current detention center. It looked incredibly out of place in between rolling hills, next to the ocean at the end of a long dirt road, but there it was. Up there, we talked about endless wars and generations in the Middle East, Africa and Asia who know nothing else but bombs and drones. Asking how many times people from the same countries and regions will continue to see bloodshed. No matter what we did, or where we went, we always got back on the topic of why we were there, and how could we not?

We went to a church and tried to go to the Muslim praying room, but it was locked and required permission. We also wanted to go to the Cuban Community Center and Radio GTMO, the local radio station but didn’t have time. Passing road signs informing us that iguanas and boas are protected species. Apparently, I thought, they have more rights than humans here.

We made our way to a beach near the detention center, we could see the road and security on our way to the beach and from where we stood, but not the detention center itself. After we took “candid” pictures of each other looking out at the beautiful vast blue sea, Timothy and I sat down. I turned to him and asked, “What do you think they (the detainees) are doing right now?” I realized this was the body of water many of them drew in their artwork, the one they can smell and hear but cannot see.

Two days later I was back at the air terminal waiting to board my flight to Washington, DC, passing the time by watching fellow passengers trickle in and browsing the Navy souvenir shop selling shirts that say “Live Free,” and “It don’t GTMO better than this.”

All the photographs were taken by Rizvi on her trip to the island from Jul. 24–30, 2022.