Kudzu is America’s most infamous weed. “The vine that ate the South”— as it is commonly called — was brought from Japan in 1876 to control the severe soil erosion that had resulted from extensive cultivation of cotton on the slave plantations across the American South. Kudzu evangelists like the popular radio host at the time Channing Cope spoke of kudzu in religious terms, as the “miracle vine” whose “healing touch” would make barren Southern farms “live again.” The kudzu plant went on to become a monstrous, fast-growing plant — it can grow up to a foot a day — and even though its myth might have outgrown its reality, it is now classified by the US Forest Service as a threat to the economy and diversity.

Like Kudzu, sugar cane’s story reflects critical junctures in historical processes of transnational coloniality. Sugar from plantations in the Caribbean and South America formed one of the three corners of the triangular Atlantic trade (the other two being enslaved people from Africa and money from Europe). Over centuries, this “white gold” transformed pre-existing biological and economic ecosystems.

Where one of these plants was used to cover up the environmental impact of the transatlantic slave economy, only to become a menace, the other was used as fuel for the transatlantic slave trade now seen as an inescapably violent bedrock in many Caribbean and South American economies. The language used in myth-making around them, kudzu particularly —“foreign,” “invasive,” “violent,” “destructive” — enforce artificial taxonomies, a kind of racialization of the natural world that traps us in frames of coloniality and oppression, a self-fulfilling prophecy that violence begets more violence.

In inviting us to consider our politics of relation and interconnectivity, Okoyomon calls us to recognize not just our place in the family of things, but also our responsibility of care in it, especially in the face of our worsening global ecological crisis.

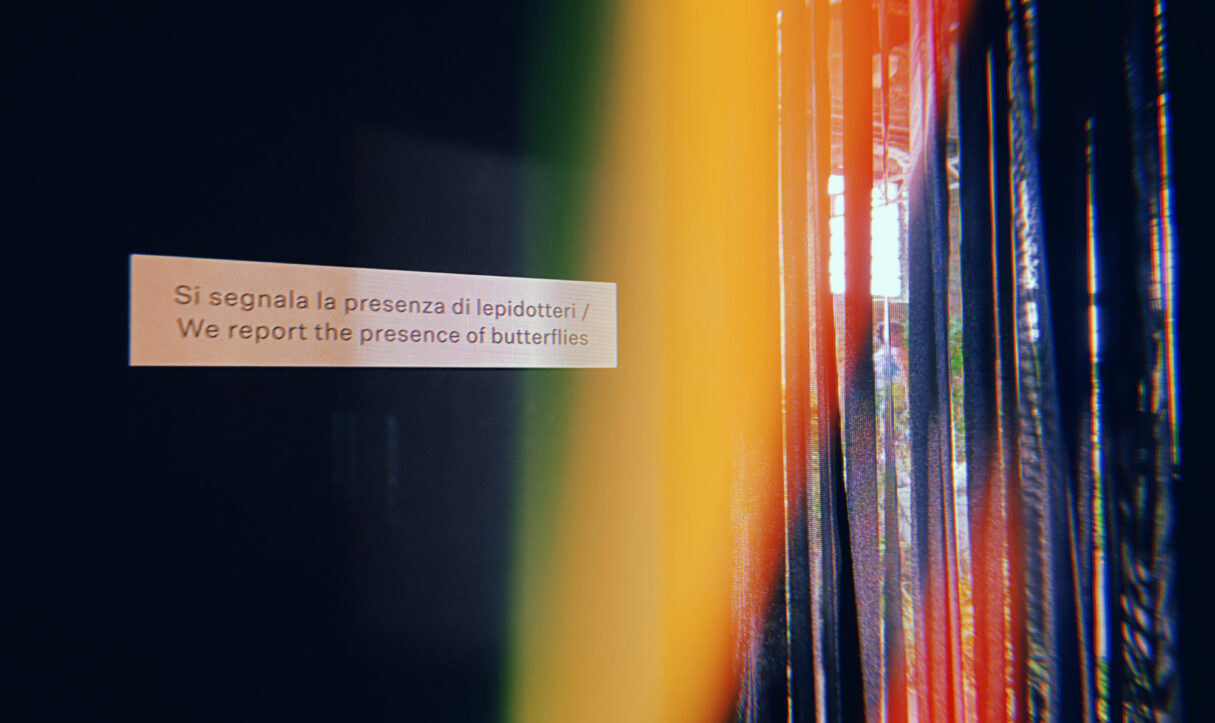

In the latest project by the artist and poet Precious Okoyomon, these two crops have once again been put in relation, this time under a new language. Titled ‘To See the Earth Before the End of the World,” Okoyomon’s show is open at the 2022 Venice Biennale until Nov. 27, 2022. In the show, the soil that roots a sprawling mass of kudzu vines and sugarcane plants also carries gently-flowing streams of water. Amidst the plants are six life-size sculptures (made out of raw wool, dirt, yarn, and blood) that Okoyomon calls deities or angels. Black swallowtail butterflies flutter around the space, dying and reproducing many times over the course of the exhibition. Madeline Weisburg’s curatorial note says the installation invokes a “politics of ecological revolt/revolution.”

LIVING METAPHORS

But building metaphors with bio art is fraught with questions of ethics and the unresolvable tension of collaborating with beings you cannot talk to. How successfully can we attribute human meanings and metaphors to other beings? In Okoyomon’s practice, one particularly concerned with racialization and coloniality, is the natural world the subaltern? And how does their bio art go beyond speaking for the subaltern to amplifying the subaltern’s voice?

It is precisely this tension that makes Okoyomon’s work captivating. Take their 2020 project “Earthseed,” for example, where the kudzu created its own ecologies as other species like crickets and snails began to thrive amidst it. There, the medium in itself was the message, an embodiment of a practice of repair. The title “Earthseed” was taken from Octavia Butler’s novel “Parable of the Sower” whose central tenet is that God is change. All literary and visual metaphors in the show pointed to a non-superficial understanding of all life as enmeshed in flux from one to the other, infinitely connected in “interlocking cycles of reciprocity,” as artist and scholar Claire Pentecost names it.

The project that followed “Earthseed” was “Fragmented Body Perceptions as Higher Vibration Frequencies to God” (2021) at the Performance Space New York. There, a snowblower scattered the ash from the incinerated kudzu at “Earthseed” over a landscape of rocks and soil. Within this landscape was a stream populated by a handful of fish. The show was Okoyomon’s response to the mass death and devastation of 2020 and the result was a space that made a physical landscape out of grief.

Around the same time, Okoyomon worked on a garden commissioned by the Aspen Art Museum (AAM) titled “Every Earthly Morning the Sky’s Light touches Ur Life is Unprecedented in its Beauty” (2021-2022). Over 18 months, Okoyomon collaborated with local growers to transform the AAM rooftop seasonally, installing a mixture of sculpture and organic matter to create a garden based on themes of pleasure, abundance, and desire. At the end of the ongoing project, the soil will go back into the community around AAM.

SHARED KINSHIP

The questions posed by Okoyomon’s projects are wide-ranging, but they weave a continued conversation on the “shared kinship of all on the land of soil and the land of water,” as Okoyomon said. And so, the material of their art practice is “everything that is living and dying, decaying, growing, rocks, dirt, water.” Their artworks and installations function as ecosystems, in which materials live and thrive, decay and die, transmitting energy from one form to another. Even among their projects, materials are recycled and brought into new forms.

In inviting us to consider our politics of relation and interconnectivity, Okoyomon calls us to recognize not just our place in the family of things, but also our responsibility of care in it, especially in the face of our worsening global ecological crisis. More precisely, this politics of relation is a politics of ecological revolution that emphasizes, acknowledges — and maybe even accepts — that change, mutation, and decay make up the “raw material feature of reality.” They are “the matrixial source code of our always already non-agential world,” as Okoyomon put it.

What matters is what we choose to do about this inescapable feature. This is what Okoyomon’s theory of mutation, flux, and motion is about: that our lives and deaths are an act of revolution, an expression of what power chooses to save or neglect, and what human power and systems can not wrestle from nature.

Through their questions, process and engagement, Okoyomon offers renewed perspectives from which we can think more urgently about how to make sense of ourselves, our place, and our responsibility in this world wrought with violence but inhabited by tender beings.

Immaculata Abba is an artist and writer.

* Quote in title from, “Precious Okoyomon On Finding Poetry in Everything,” an interview by Willis Plummer.

* Ambient film from Precious Okoyomon’s installation “To See the Earth Before the End of the World” at the Venice Biennale, July 29, 2022. Shot by Allyn Gaestel.