The scene is now a familiar one: Thousands of white supremacists violently storm a meeting of government officials convened near the nation’s capital. Members of right-wing paramilitary groups roam the building unopposed, eager to disrupt leaders’ negotiations to facilitate a peaceful transfer of power in the shadow of contentious national elections.

I’m not talking here about the US Capitol on Jan. 6, but South Africa’s World Trade Center on June 25, 1993, when 3000 white supremacists stormed the site of negotiations for South Africa’s first free, multi-racial elections.

The United States’ Jan. 6 and South Africa’s June 25 attacks were not isolated incidents. Rather, these attacks were a natural culmination of a far-right that believed themselves locked out of power in an electoral process no longer designed — or rigged — to preference them. Violence, then, would be the only option.

But what can white supremacy in South Africa teach us about white supremacy in the United States? While at first glance quite different, these right-wing white supremacist movements — and their relationship to military and police forces — have a great deal in common. An examination, therefore, is warranted.

WHITE SUPREMACY IN SOUTH AFRICA

Subsequent investigations following the June 25 attack revealed the South African military’s favoritism for the far-right aided the assault. According to the Goldstone Commission, the investigative body tasked with examining the invasion, the performance of South Africa’s police and military amounted to a “dereliction of duty.” The commission further stated that it was beyond justification that South Africa’s police and military accepted assurances from known white supremacist terrorists and paramilitary groups that “protests” would be non-violent.

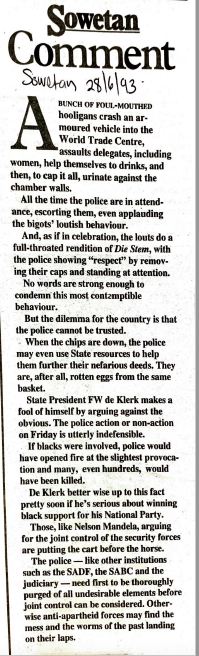

Few South Africans, however, were shocked by these revelations. Major anti-apartheid organizations like the African National Congress and the Pan Africanist Congress expressed outrage at the security forces’ persistent complicity in far-right violence. South African newspapers ran hundreds of editorials in the months following June 25, condemning the security forces’ response. As Sowetan — one of South Africa’s largest English national daily newspapers — put it on June 28, 1993, the security forces needed “purging of all undesirable elements” for negotiations to continue in good faith.

Few South Africans, however, were shocked by these revelations. Major anti-apartheid organizations like the African National Congress and the Pan Africanist Congress expressed outrage at the security forces’ persistent complicity in far-right violence. South African newspapers ran hundreds of editorials in the months following June 25, condemning the security forces’ response. As Sowetan — one of South Africa’s largest English national daily newspapers — put it on June 28, 1993, the security forces needed “purging of all undesirable elements” for negotiations to continue in good faith.

The country’s history supported the anti-apartheid organizations’ arguments. Since 1948, apartheid — a system of institutionalized racial segregation — governed the country. South Africa’s military was, by definition, created to defend the white regime. Even more worrying, South Africa’s “Commando” structure facilitated infiltration by violent white supremacists. Tasked with paramilitary defense, the Commandos operated as a local counterinsurgency force within South Africa. The Commando’s decentralized nature left the divisions open to infiltration by far-right actors, especially in rural areas that vehemently opposed apartheid’s end. The Commando leadership admitted to high levels of right-wing activity within their ranks in the lead-up to the election. The Commandos’ institutional culture — highly influenced by the white Afrikaner tradition — combined with tight bonds between the Commandos and local government, police, and community groups resulting in strong support of the far-right.

As in the United States, revelations of violent white supremacists with military and police experience alarmed the public. After a former police officer murdered eight people in Pretoria in 1988, the far-right command’s security force background emerged. These men used their military experience to justify their far-right leadership role.

There were, however, limits to the relationship between the far-right and the military. The far-right’s decision to terrorize the ruling National Party diluted the far-right’s appeal to military leadership, which remained loyal to the government. Furthermore, the South African far-right’s diffuse nature made it difficult for the military to track, categorize, and combat these groups, even as the organizations themselves became more violent and vocal.

While the South African security forces arrested and infiltrated far-right organizations throughout the 1990s, the crackdown usually came only after a specific attack or a series of bombings, threats, or thefts by the paramilitary right.

For instance, take the first two years of white supremacist terror campaigns in South Africa, beginning in 1990:

Unbanning of anti-apartheid groups on February 2, 1990 → Massive mobilization of the far-right → Far-Right Rally in Pretoria, 30K-130K on May 27, 1990

Crackdown by security forces → Mobilization, reorganization of terror campaigns → “Battle of Ventersdorp,” far-right disrupts National Party Speech on August 9, 1991

This pattern of mobilization, culminating incident, and crackdown accelerated in the lead-up to the 1994 election, with the June 25 attack initiating one of the largest crackdowns by security forces. The cycle’s final act occurred on April 25, 1994 when just two days before the election, the far-right set off an almost 200-pound car bomb — the largest yet — at the African National Congress offices in Johannesburg, killing nine and injuring hundreds. Again, security forces played catch-up, arresting dozens of paramilitary right-wingers in the weeks following the explosion.

Investigative bodies, like the Goldstone Commission, put pressure on South Africa’s military to purge white supremacist terrorists and to avoid the “appearance” of collusion. Critically, South Africa’s military participated in negotiations to form a post-apartheid army — the South African National Defense Force. This force combined the government’s military with guerrilla forces from major South African liberation organizations. While hardly equitable, the military’s membership in a post-apartheid army sent a powerful signal to far-right organizations that the South African military would respect the 1994 election’s outcome.

LESSONS FROM SOUTH AFRICA

In the United States, while the Jan. 6 investigations remain ongoing, a disturbing trend emerged in the weeks after the attack: US military veterans’ disproportionate presence amongst the rioters. Out of the over 140 arrests, nearly 1 in 5 have served or currently serve in the US armed forces. Attackers include Air Force veterans, a retired Navy SEAL, former Marines, Army personnel, and active duty law enforcement from across the country. In response to Jan. 6, US law enforcement launched “likely the most complex investigation ever prosecuted by the Department of Justice,” with the investigations already including over 400 cases.

Yet, the South African government’s approach is instructive here — the US military cannot just try to ban all white supremacist sympathizers. We must identify and dismantle the structures that incentivize joining in the first place.

What can the US military learn from the South African case? South Africa’s security forces initially responded to this threat in the same way that the US government responded to the siege on the Capitol — by cracking down on far-right groups. However, eradicating specific organizations was only a temporary solution. The far-right proved extremely capable of reorganizing, putting security forces always in the position of playing catch-up.

The Department of Defense’s prohibition of soldier’s “active participation” in white supremacist groups has come under justifiable scrutiny in the aftermath of Jan. 6. The US military would not be the first to try and draw a distinction between “active” participation and passive membership in white supremacist groups. The South African military tried a similar approach by banning soldiers from membership in the country’s most vile and violent far-right groups, like the Blanke Bevrydingsbeweging (White Liberation Movement) and the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement). In February 2003, the South African government took the bold step of phasing out the Commando system, citing continued human rights abuses against Black civilians and its historical role in the apartheid system. Disbanding the Commandos, however, has not resolved persistent problems in other South African military and police branches of collaborating with white supremacists and discriminating against Black South Africans.

Yet, the South African government’s approach is instructive here — the US military cannot just try to ban all white supremacist sympathizers. We must identify and dismantle the structures that incentivize joining in the first place. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s call for a 60-day “stand down” on extremism in the military is a good, but insufficient start. Early arrests also seem to indicate that this problem affects some branches more than others — 18 of the Capitol attackers served in the Marines and 11 in the Army, with only two in the Navy and two in the Air Force. From its Confederate bases to its refusal to collect reliable data on service members discharged for white supremacist ideology, the US military continues to take a soft line on the threat.

CHANGING BEHAVIOR IS NOT ENOUGH

The South African National Defense Force — tasked with integrating former white military personnel with Black liberation forces — had to deal with institutionalized white supremacy. The South African military’s affirmative action and reconciliation initiatives, while flawed, were a serious attempt to address white supremacy in its ranks. But changing institutions is not easy work. Two decades later, the South African National Defense Force still struggles with integration and retention, force effectiveness, and persistent anti-Black racism in its treatment of its citizens, which has only accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the days after Jan. 6, the US military’s Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a joint statement condemning the violent rioters. While military leadership maintains that they take the threat seriously, current and former service members insist that this problem began far earlier than the Capitol attack. The burden in the US military of combating white supremacy in the ranks often falls to minority service members, over half of whom report that they have “personally witnessed examples of white nationalism or ideological-driven racism.” Military leadership acknowledges that its personnel are “prized recruits” for white supremacist groups because of their training. Still, officials prove less willing to confront the armed forces’ historical and contemporary complicity in violent white supremacy.

As civilian and military leadership in the Pentagon rethink combating white supremacy, the South African case reminds us that focusing on changing individual behavior is not enough. Institutional failings facilitated violent white supremacy, and that reality requires the difficult work of fighting white supremacy at the heart of our military institutions.

Augusta Dell’Omo is an Ernest May Predoctoral Fellow in History and Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center and a PhD candidate in History at the University of Texas at Austin. She specializes in white supremacist violence and terror, US foreign policy, and US-South African relations.