To recite the chorus of my favorite song by Alberto Cortez, a cover of Facundo Cabral’s original tune:

“No soy de aquí

Ni soy de allá

No tengo edad

Ni por venir

Y ser feliz, es mi color de identidad”

“I’m not from here

I’m not from there

I have neither past nor future

And being happy is the color of my identity.”

When Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began, my mind flurried to all sorts of things: disinformation/misinformation campaigns, the risk of nuclear escalation, the flux of fleeing people, and the return of a Cold War-esque world.

Nuclear deterrence advocates say that deterrence is at work between the United States and Russia, but it has allowed Russia to ransack Ukraine. And while no nukes were found on Ukrainian soil, I saw the destruction unfolding before me: The cries of agony and fear, streets blown up, civilians scurrying away from the mayhem.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine matters to me because it delineates the intricacies between nuclear arms control, immigration, and the conflicted identities of those of us who were forced to grow up away from our “homeland.”

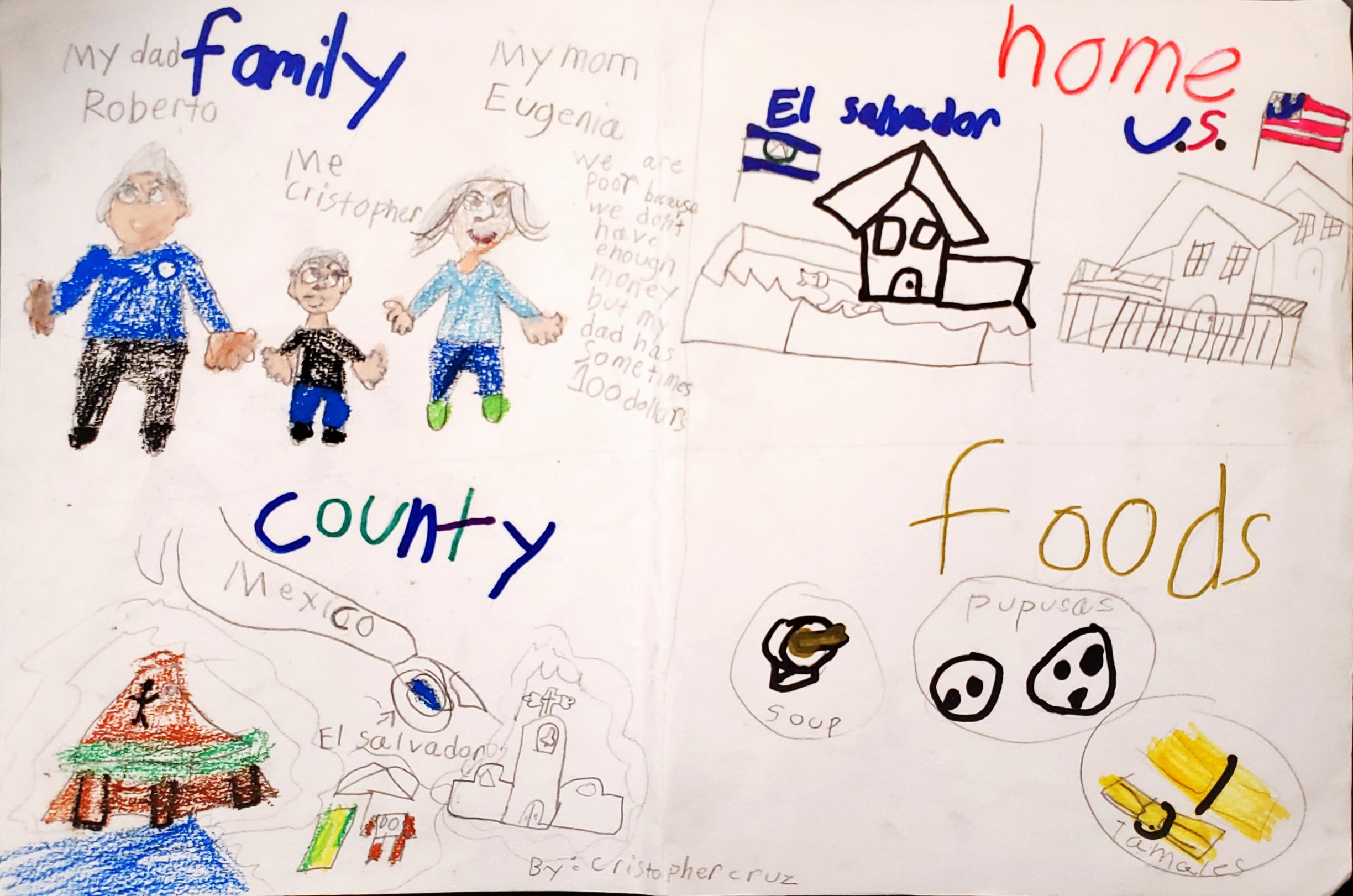

And then I remembered the tales of my parents, stories they’ve told me since I was young, of their experiences surviving the civil war in El Salvador. My father saw the brunt of the conflict from guerilla-occupied territories and vividly recalls the colors and sounds of the Salvadoran Air Force conducting air raids over his roof. My mother, on the other hand, had to accompany her father to free her siblings from being detained at the Police Castle (yes, that’s the actual name of the building) in the Capital for “violating” curfew and had to be careful of the sites she would frequent with her friends. While my father’s extended relatives fled to Sweden, his nuclear family remained behind. My mother’s opportunities to move to the US were shut down because her mother had fled El Salvador before the start of the civil war.

I often joke that it’s thanks to President Ronald Reagan that I’m here. His administration opened the doors for my grandmother’s immigration to the US and subsequent citizenship. His administration also helped destabilize El Salvador and plunge it into decades of corruption to quash the threat of Soviet influence. Peace accords were signed in the early 1990s. A conservative government took over El Salvador, members of whom were complicit in the murders of innocent people — and blessed it with US government support for these heinous crimes.

Why does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine matter to me, as a Salvadoran-born American living in South Central Los Angeles and who advocates for nuclear nonproliferation? It turns out, a lot.

WHAT I CHOSE AND DIDN’T

Like in El Salvador, no nukes have been deployed or used in Ukraine, but their existence has allowed the conventional conflict to escalate to catastrophic levels on the ground.

I didn’t choose to be brought to the United States. Still, I did choose to be a part of the nuclear arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament field because I found it to be the place where I felt the most “myself,” despite extremely good-faith criticisms from older white individuals in the field and rejections from top universities. I refuse to be siloed into a specific issue area because of my ethnic and cultural background and community of residence.

My now deceased grandmother petitioned for my mother and me to move in with her in Los Angeles. Los Angeles, where opportunities for science and diplomacy are few and far between, and the hottest topics are housing, immigration, and occasional fights with urban oil drilling sites.

This is why I went all in with Nuclear Free Schools (NFS) with my high school classmates: One executive order and the world gets nuked. Unfortunately, when NFS was launched, gun control dominated the airwaves, leaving very little room for young people concerned with nuclear arms control to voice our opinion — young people whose families and origins are Latin American.

Did you know that Latin America was the first-ever Nuclear Weapons Free Zone? Because of the Treaty of Tlatelolco of 1967, such “free zones” exist. El Salvador, the country I was born in, has been a member state since 1968, and that same treaty was our source of inspiration in the creation of NFS.

While my parents in El Salvador were able to weather the Cold War, the country did not. With the “reorganization” of the government and the US recklessly deporting gang members back to El Salvador, it was a recipe for disaster. Salvadorans were already robbed of life, opportunity, and liberty thanks in part to the Civil War. Still, now they had to deal with a sudden uptick in criminals, further stymieing the growth and healing of the country. The 1990s and 2000s witnessed mass migration movements of people from El Salvador claiming to flee from violence. While my family and I never put up with any gangs while living in El Salvador, my mother knew that opportunities for growth and stability were few. Her bringing me along on board a TACA Airlines flight on Mar. 8, 2003 to LAX, was no different.

Fast forward to my young adult years, and I know that if it wasn’t for groups like the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization Youth Group (CYG) and the Critical Issues Forum (CIF), I would have had a more challenging time breaking into this field. In fact, it was easier for me to join groups abroad than it was in the United States. CIF, CYG, and NFS allowed me to explore and accept my identity as a Latin American immigrant fighting for a world free of nuclear threats, despite living in a country that prides itself on diversity and inclusion.

AMERICA’S DOUBLE STANDARD

In the last decade, the US government has started using terms like “diplomacy,” “diversity,” “inclusion,” and “justice” to explain its nuclear and immigrant policies. Yet, all of these have an inherent double standard that I have been processing since I started advocating for a nuclear-weapons-free world.

Is it “diplomacy” when things like nuclear weapons serve as a shield for military operations in foreign countries? You know, the kind that we condemn Russia for, despite an American invasion in Iraq in 2003, the same year I arrived in the US. And for those who may have forgotten, the George W. Bush administration justified its attack on Iraq by claiming that Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction. Eventually, the claim was proven to be bogus, not only after thousands of Iraqis lost their lives. Nevertheless, Iraq continues to be unstable. Similarly, is it diplomacy when the US actively discriminates between refugees? Why can’t those fleeing Central America and Afghanistan be welcomed the same way?

Is it “diversity and inclusion” when you have the Pentagon nixing non-pro arms control experts in favor of war hawks and profiteers? What about diversity when funding is pulled by the MacArthur Foundation? What about when professors and people in power tell people like me (i.e., immigrant, Spanish-speaking, middle class, etc.) that my passion for nuclear policy is a “phase” or that I would be better suited for a career that requires me to speak Spanish because my Spanish is “so good!”?

Is it “justice” when people of color that suffered from the nuclear tests outside of the American States cannot qualify for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act? Currently, the act has not been accepted by both chambers of Congress and is only available to people affected “by nuclear testing fallout, uranium mining, mills & transport, many of whom are tribal members.” Furthermore, the compensation is a one-time payment, and despite its description, many Indigenous Americans don’t even qualify.

HOW I PROCESS AMERICA’S HYPOCRISY

Per UNICEF, we have 2 million children fleeing Ukraine. Children that will likely not grow up in their birthplace, the way they remember it, with the people they remember. Children that might go on to be involved in international politics may have an easier time joining the field than I did. They are circumstantial immigrants like me, but there’s a big, white difference.

As an advocate for nonproliferation and the abolition of nuclear weapons, the US double standard in its nuclear and immigrant policies stands out. I don’t always feel good about representing the US in my work, and I have varying levels of guilt associated with compassion and indifference toward those fleeing violence to come to the US. Yet, as I process all of these emotions, I know one thing: We, Americans, have our work cut out for us.

At the micro-level, we need to be more inclusive to avoid maintaining oppression and be equally compassionate to all who suffer within and outside our communities. Finally, at the macro level, the US government needs to adopt an anti-racist foreign policy, reform the immigration system, and commit to the Non-Proliferation Treaty’s Article 6 obligations as well as ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. These combined reforms will eventually get us close to a nuclear-weapons-free world — and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its nuclear threats have taught me that we can’t wait any longer.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine matters to me because it delineates the intricacies between nuclear arms control, immigration, and the conflicted identities of those of us who were forced to grow up away from our “homeland.” Nuclear weapons didn’t save lives in El Salvador, and they’re not saving any in Ukraine. Nuclear weapons allow for indiscrimination at personal, professional, and strategic levels.

If this field doesn’t work out, I guess it’s time to explore “Plan B” and go back to gawking at animals.

Cristopher Cruz is a student, geek, and writer. He functions as a Communications Coordinator for the CTBTO Youth Group and Co-Founder of Nuclear Free Schools. Cristopher runs his own bilingual blog called The Atomic Scholar, where he writes about his adventures in the nuclear field as a Salvadoran-American. When not canceling nukes, he can be found roaming museums and parks or watching Godzilla movies.

This piece is published in collaboration with Outrider Foundation, a nonprofit media group that publishes commentary on security issues, public policy, and social justice.

For the Spanish translation, see here.