One of the most important assumptions made about nuclear weapons during the first years of the Cold War was that their immense size and awesome destructive power would translate into significant military utility.

Below are their awe-inspiring characteristics, which for all intents and purposes, are useless when it comes to real protection, real safety, and real utility.

EXPLOSIONS

Nuclear weapons have been called the ultimate weapon for so long, it takes a genuine effort to think of them objectively. They have achieved a kind of dream-like “bogeyman” status in our minds.

But they are not anything like an ultimate weapon. In the taxonomy of weapons, nuclear weapons fall into the class of explosives — and they inherit all the limitations that explosives have. Explosions can’t: defend, guard, occupy, capture, conquer, reconnoiter, pacify, feint or make a show of force, and so on. War, because it is a complex undertaking, requires flexible tools. Soldiers are extraordinarily flexible military tools while explosives are not. All they do is blow up, destroying whatever is nearby.

Despite the impulse to imagine that an evil person with nuclear weapons could do whatever he wanted, nuclear weapons are not nearly so useful. For example, Adolf Hitler could not have carried out the Holocaust with nuclear weapons because the Jews of Europe were living side by side with non-Jews. Using a nuclear weapon to kill German Jews would have inevitably also killed millions of non-Jewish Germans.

There is no doubt that nuclear weapons are the most destructive explosives there are but large explosives are rarely useful — especially during a war.

SIZE

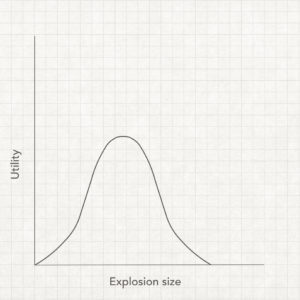

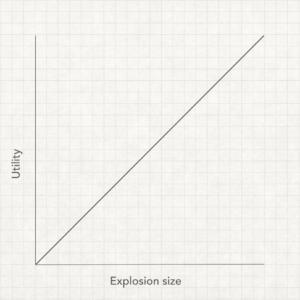

The size of nuclear explosions is awe-inspiring, but wars are not fought with awe. Their size is actually a practical limitation, not a benefit. Most people imagine that bigger weapons are always more useful than their smaller cousins. If a pistol won’t do the job, get a rifle; if a rifle won’t work, get a bazooka; and so on. When they picture the relationship between explosion size and utility, they think of a graph that looks something like Graph A.

For each step up in the size of the explosion there is a corresponding increase in the utility of that explosion. But the reality is actually more like Graph B.

Initially, increases in size do lead to increases in effectiveness. But as you continue to increase the size, the effectiveness starts to diminish. And at some point increases in size stop helping. Eventually they lead to decreases in effectiveness, because you start to destroy so much stuff that you didn’t intend to destroy that the weapon does more harm than good.

The problem with big explosions is that there are very few targets in war large enough to justify their use. The goal of war is to kill or convince your adversary’s military forces to give in, not just to randomly destroy stuff. Therefore, the most frequent targets in war are soldiers, vehicles that carry soldiers, buildings associated with making war, and now military drones and robots. Occasionally somewhat larger targets are important, like supply dumps or airports. But for all practical purposes, targets in war are almost always building-sized or smaller — headquarters, barracks, research buildings, etc. So in almost every case, conventional bombs are the biggest bombs you need. Larger targets can always be destroyed using a collection of smaller bombs. The ideal weapon allows you to kill or disable enemy soldiers discriminately — without harming your own soldiers, bystanders not involved in the fighting, useful structures, or other things of value. Past a certain size, therefore, large explosions are clumsy rather than useful.

This is in keeping with the nature of tools because ultimately, weapons are a subspecies of tools. The utility of tools is not measured by their size. Their usefulness depends on the match between their characteristics and the situation. For example, a screwdriver is ideal for removing an electrical outlet cover, but you wouldn’t want to paint a barn with one. Similarly, an artillery piece can be useful against soldiers caught in the open, but it is useless underwater. It is the correlation between characteristics and circumstances that matters, not size. When a repairman sends his assistant to the truck he doesn’t say, “Darren, bring me back the biggest tool for the job.” He tells Darren to bring back the right tool for the job.

Large, indiscriminate explosions are by definition not very useful weapons.

LACK OF BATTLEFIELD UTILITY

Nowhere is this size problem clearer than on the battlefield. When your soldiers are in close contact with the enemy’s, nuclear explosions over your adversary’s forward positions will kill some of your soldiers, too. Nuclear weapons dropped in the rear areas of your adversary’s forces might be less harmful to your own troops, but they are still not ideal.

Nuclear weapons also leave a trail of poison wherever they’re used: Drop a nuclear weapon on your adversary’s troops and the wind can blow radiation back on your own troops. Radiation is an odorless, tasteless, invisible poison. It is hard to detect and it can remain on surfaces for days, weeks, or even years (although most of its immediate lethality degrades within days). Even relatively brief exposure can incapacitate or kill soldiers. Radiation — floating through the air as fallout, deposited on exposed surfaces — poses a deadly danger to your own soldiers as well as your adversary’s.

A nuclear battlefield, therefore, has two requirements. First, you must consider which way the wind is blowing before you launch an attack. This puts you in the position of holding off on potentially vital attacks while you wait for the weather to cooperate. But the wind is often unpredictable. Second, it requires that you either institute cumbersome protection and decontamination procedures — and therefore let military efforts grind to a standstill while you wipe and clean — or that you be willing to lose some of your own soldiers to radiation poisoning. In effect, using nuclear weapons on the battlefield means killing some of your own soldiers.

Finally, the way that the power of nuclear weapons is typically presented exaggerates their battlefield utility. The power of an explosion is often depicted by showing circles of destruction overlaid on maps of cities. This is profoundly misleading. Not because nuclear weapons don’t create a great deal of destruction, but because cities are, for the most part, not like battlefields. The average population density in New York City is 27,000 people per square mile. Drop a Hiroshima-sized nuclear weapon on New York City and you can kill tens of thousands of people in an afternoon. But the average population density of Nebraska, for example, is 24 people per square mile. Drop a Hiroshima-sized bomb on Nebraska and you’re likely to kill no more than a school-bus-full of people. When thinking about the military utility of nuclear weapons, it is important to keep in mind that battlefields are a lot more like Nebraska than New York City.

The historical record, therefore, shows experienced military professionals looking at wartime situations again and again, and resisting the thought of using nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons are far less effective on the battlefield than you might at first imagine, and in some circumstances their use would create extraordinary obstacles. The historical evidence reflects these limitations. Consider the Korean War. When Eisenhower became president in 1952, he asked about the possibility of using tactical (i.e. smaller, battlefield) nuclear weapons in Korea. The response was not encouraging.

Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins said he was “very skeptical” about the military advantages; Chinese and North Korean forces were deeply entrenched along a 150-mile front, and recent bomb tests in Nevada had proven “that men can be very close to the explosion and not be hurt if they are well dug in.” Other national security officials agreed, and a study by National Security Council staff also concluded that they could not be sure that the use of atomic weapons would be effective.

In 1954 when French forces were surrounded at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam, the Eisenhower administration offered to use three small nuclear weapons to try to relieve the French garrison. The French government, unsurprisingly, declined the offer. Nuclear explosions over Viet Minh positions would kill too many French troops nearby and, depending on the wind, radiation might kill even more.

Similar discussions about the use of nuclear weapons occurred during the Taiwan Straits crises in 1954 and 1958. But again, nuclear weapons were not used. As the historian John Lewis Gaddis explains:

. . . there could be no assurance, whether in Korea, Indochina, or the Taiwan Strait, that the use of nuclear weapons would produce decisive military results. Their ineffectual use, moreover, might compromise the overall deterrent: if the bomb was seen to have no dramatic effect upon the North Koreans, the Chinese Communists, or the Viet Minh, then how could it be expected to impress the Russians, or to reassure endangered allies?

When US Marines were surrounded at Khe Sanh in 1968 (in a predicament much like the French at Dien Bien Phu), General Westmorland requested that the use of nuclear weapons be considered. His request was rejected. And during the run-up to the Gulf War (1990–1991), when Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney asked General Colin Powell to explore the use of nuclear weapons against Iraqi forces, the report that resulted demonstrated the difficulties and drawbacks of the plan so clearly that the idea was dropped and the reports destroyed.

The historical record, therefore, shows experienced military professionals looking at wartime situations again and again, and resisting the thought of using nuclear weapons. Not because the weapons were too horrible. Not because it would have been immoral. But for hard-headed, pragmatic reasons: it wasn’t clear that these powerful explosives could be turned into practical military advantage.

ATTACKING HOMELANDS

But what about using nuclear weapons to attack cities? Wouldn’t their enormous power be used to its utmost then? Can’t you defeat a nation by destroying it utterly?

The anachronistic notion that nuclear weapons could usefully be used against homelands comes down to us from the Cold War and grew out of the circumstances of the time. In the years following World War II — and for most of the Cold War — the world was separated into two groups: two great powers that were vastly more powerful than any other country and a collection of smaller, less powerful countries. Many European and Asian countries had been left devastated by the war. The United States and the Soviet Union stood like twin towers — far taller than all the others and dominating the skyline. This bi-polar configuration led to the notion that it might be possible to get some benefit from fighting a nuclear war.

In any nuclear war, of course both sides would be left more or less crippled. But in a world where only two countries were really powerful, it was possible to imagine that after the war one of those two countries would eventually rise again and “win.” If your country were less devastated by the nuclear war than your adversary, you might recover faster and then after a few years be able to resume your towering status as world leader. There are studies from the Cold War estimating how many years it might take for each side to rise from the ashes based on various war scenarios. Today, however, such a scenario is not possible.

In today’s world, fighting a nuclear war always means losing.

In a world where there are many possible world leaders that are all about the same size and strength — the United States, Russia, China, and perhaps a united Europe — there is no path to victory after your homeland has been devastated. “Winning” simply isn’t possible. If the United States and Russia were to fight a nuclear war, both would emerge shattered, starving, and desperate. Neither would have the requisite time to get back on his feet before some other country stepped in to dominate the world. With the United States and Russia both devastated, China would immediately assume world leadership. After a nuclear war between the United States and China, Russia would probably dominate the post-war world. In a bi-polar world, dreams of eventually rising from the devastation of a nuclear war might have been defensible. In a multipolar world, such notions make no sense.

NOT VERY USEFUL AFTER ALL

So the evidence shows that nuclear weapons aren’t very useful tools of war on the battlefield. They’re too big and leave too much poison in their wake to be helpful in winning wars. And it isn’t possible to imagine a scenario where their use against cities in homelands would lead to “winning” in any meaningful sense.

Nuclear weapons are frightening and awe-inspiring. But it’s just not clear that they’re all that useful as weapons. Like a frightening mask, nuclear weapons may inspire dread; it’s not clear that they confer much advantage once the actual fighting begins. If nuclear weapons were truly useful weapons, it seems realistic to imagine that they would have been used over the last three-quarters of a century on the battlefield. Nuclear weapons appear to be virtually useless on the battlefield and even their use as society-smashers would be a pointless act of self-devastation.

The second step in eliminating nuclear weapons, therefore, is to objectively reassess their military utility and conclude that they are tools of war with very limited uses.

Ward Wilson is the executive director of RealistRevolt.

This is the second of four articles examining the state of the assumptions at the root of nuclear weapons thinking. The first is here.