In her 2020 book “Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World,” journalist and historian Lesley M.M. Blume tells the story of how John Hersey, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and war correspondent who had covered World War II for Time, went on to write for the New Yorker magazine, breaking through America’s post-war occupation and censorship apparatus imposed on Japan to reveal the true horrors of the bomb.

Although other reporters had reached Hiroshima and Nagasaki before Hersey, their reports were intercepted, contradicted, or co-opted, and failed to have the impact Hersey would achieve following his May 1946 reporting trip to Hiroshima.

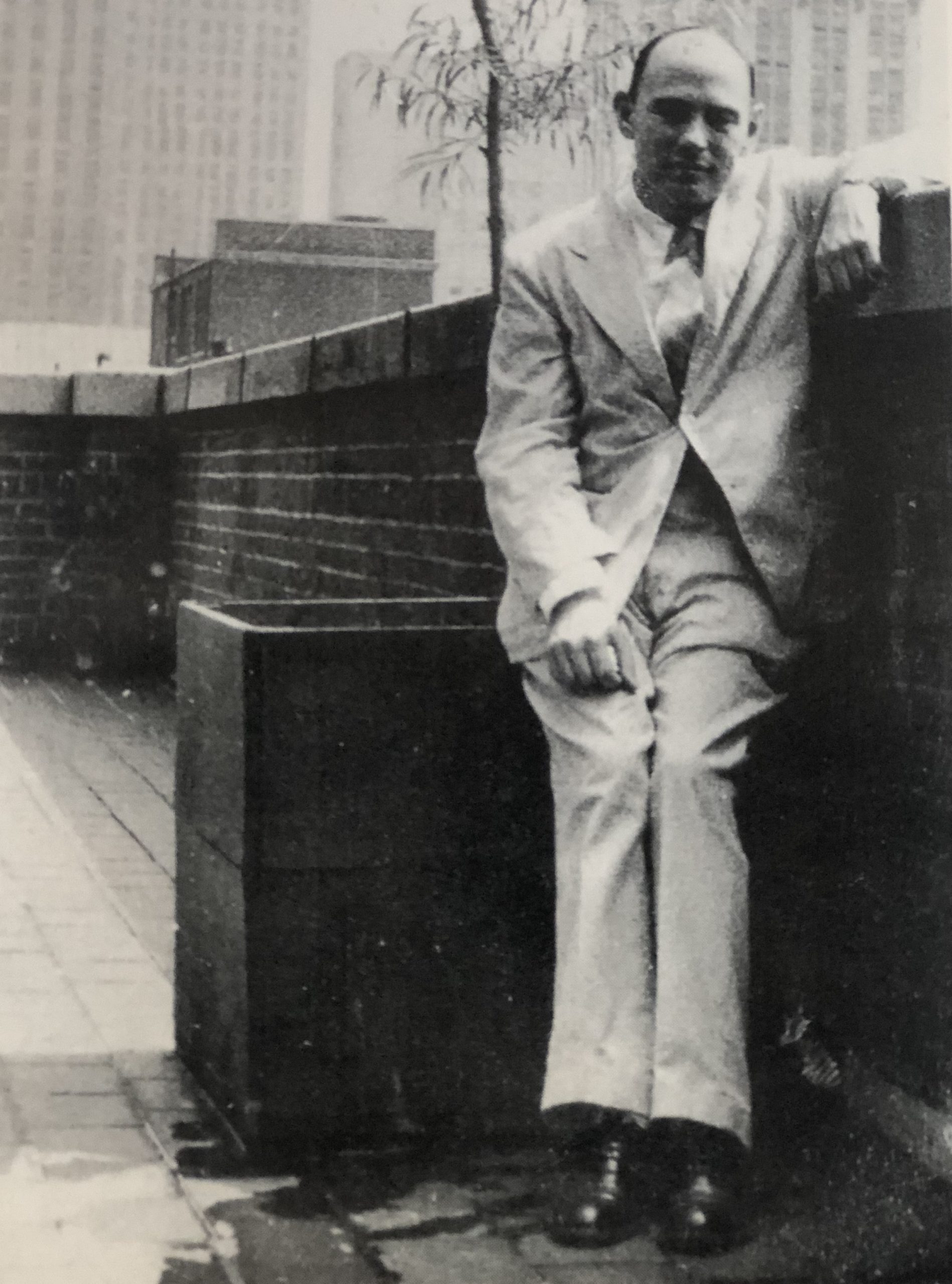

Hersey on assignment in China in 1946. (Photo by Dmitri Kessel/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Image.)

Hersey’s 30,000-word exposé, simply titled “Hiroshima,” occupied almost the entirety of the August 31, 1946 issue of the New Yorker. At a time when Japan was branded as an enemy nation in glaringly racist terms, Hersey humanized the residents of Hiroshima as he documented how six ordinary people experienced the first wartime use of the atomic bomb.

“Hiroshima” debunked the US government lie that widespread radiation deaths were mere Japanese propaganda meant to garner sympathy and punctured Lieutenant General Leslie R. Groves’s perverse claim that radiation poisoning could be “a very pleasant way to die.”

Painstakingly researched, Blume’s “Fallout” is a compelling narrative of how Hersey and his editors upstaged larger, more prestigious publications, overcoming US military, government, and media censorship to present the world a plain-spoken, yet shocking account of the human toll exacted by nuclear weapons. As Hersey describes in the book, “Hiroshima”:

“The eyebrows of some were burned off and skin hung from their faces and hands. Others, because of the pain, held their arms up as if carrying something in both hands. Some were vomiting as they walked. Many were naked or in shreds of clothing.”

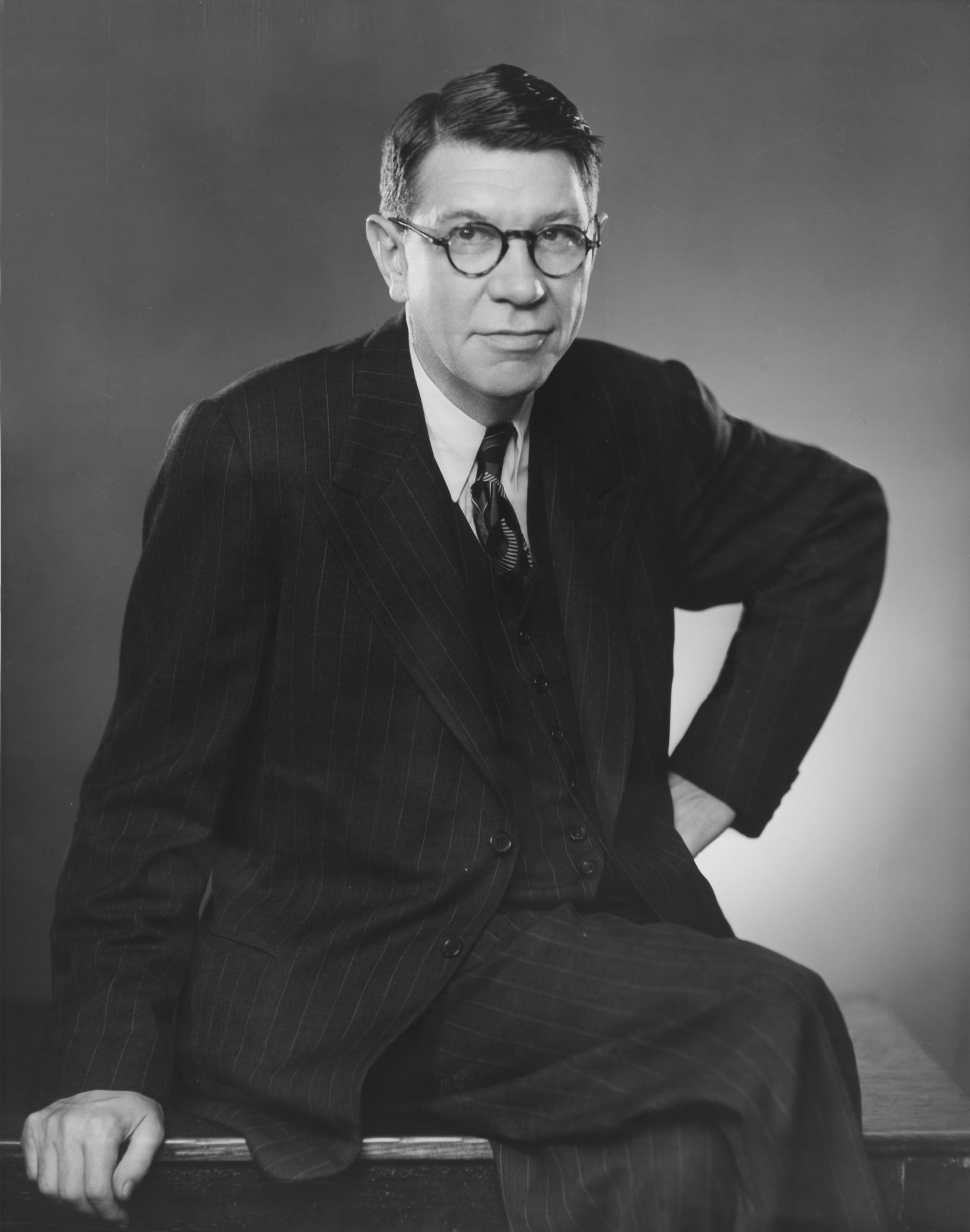

Portrait of American journalist, editor, and founder of the New Yorker magazine Harold Ross (1892 – 1951) as he sits on a desktop, one hand on his hip, New York, New York, 1948. (Photo by Bachrach/Getty Images)

Seventy-six years after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, using nuclear weapons in battle remains taboo, arguably in part thanks to the grim narrative of Hersey’s reporting. But nuclear weapons spending is up and arsenals are both expanding and modernizing, largely out of sight and free of scrutiny.

Enigmatic and under-reported, today’s nuclear landscape is increasingly perilous, making Blume’s study of “Hiroshima” even more urgent. Below Blume discusses Hersey’s reporting and what journalists can learn from his seminal work.

Jon Letman: Let’s talk about how John Hersey and his editors at the New Yorker shifted the narrative about the bomb’s use and more broadly impacted public trust in the US government. This shift was not just in the US but around the world, right?

Lesley Blume: The international impact was immediate, widespread, and profound. Up to that point, the government narrative had been that the bombs were essentially conventional “megabombs.” Obviously there was a new devastating quality to them. They could obliterate a city with one bomb as opposed to requiring a fleet of bombers, but the narrative of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had really been elaborately downplayed until Hersey got in. He and his editors Harold Ross and William Shawn were determined to show that these were not conventional megaweapons. With the entrance of these bombs into warfare, humanity had entered an entirely new phase of existential threat. That single report of one reporter going back into very well-trodden territory and coming out with this revelatory report changed not only the narrative about nuclear weapons forever but it also began to shift the American public’s relationship of accepting government narrative.

Do you think Hersey’s “Hiroshima” was a fundamental turning point in how people perceive their government?

Yes, it created distrust… but there was also and remains a really big contingent of readers of “Hiroshima” who knew that they’d been lied to or the bomb had been mischaracterized and they didn’t care. It almost made them double down at how enraged they were at the Japanese. There has always been, even after “Hiroshima” came out, a huge part of the population that says, “actually, we don’t care. They got what they deserved.” It’s almost like the government lie and coverup is irrelevant.

As you wrote in “Fallout,” Hersey humanized the Japanese when nearly a quarter of Americans surveyed said they “wished the US had been able to use even more atomic bombs on Japan before the emperor had surrendered.” In recent years, both Democrats and Republicans have threatened to bomb Iran, North Korea, and there’s a growing frenzy around China. How different are Americans today compared with 76 years ago in terms of our willingness to view other people as legitimate nuclear targets?

There’s a disturbing trend in American attitudes for sure right now. There was a survey where one-third of the respondents were in favor of a preemptive strike on North Korea even if it meant that a million civilians would die. That’s a pretty astonishing statistic and revelation.

I would say that the population of 2021 has a lot in common with the population of 1945, but is very different from the American population of the 1950s, 60s, or 70s where the revelations of what nuclear warfare were still fresh and there was a really visceral horror of nuclear weapons. The fact is that nuclear weapons have not been used in wartime since Nagasaki and we’re several generations removed from that. All of a sudden there’s an increased apparent tolerance for the idea of using those weapons as a convenience, as a cost saving mechanism. It’s a really disturbing trend and it leads back to the issue of dehumanization which I really rake through in my book and that Hersey raked through in his own work. The inclination to dehumanize is back big time and it’s getting worse.

I remember seeing a report on the correlation between people’s ability to locate a place on a map and their willingness to bomb it. I think the example was North Korea, with those who supported using military force being less able to find it on a map.

This doesn’t surprise me at all because the less seen the population is, the easier it is to bloodlust after its potential annihilation. I think that one reason Hersey’s report was so profoundly effective was because up to the point of the report’s release the Japanese had been just a really loathed idea.

One way of covering the suffering inflicted by nuclear weapons is to report on the impacts of nuclear testing in places like the Marshall Islands, Kazakhstan, or among downwinder communities where bombs were tested or developed. How effective is this kind of reporting?

It could be enormously effective because frankly not that many people really know about the literal fallout of testing communities. Most Americans would be shocked at how many downwinder communities there are in our own country. That kind of reporting can have an enormous impact.

There’s a unique aspect to covering nuclear stories. News tends to prioritize a story when something’s already happened. A lot of the coverage I’m talking about is still in the realm of possibility so suddenly it’s not as sexy a story. But the thing with nuclear crisis is the aftermath could be so catastrophic that there’s no such thing as aftermath reporting. All we have is preemptive reporting and that’s not how many publications operate, so the challenge is especially complicated.

One other challenge we have gets back to reporters and editors on the nuclear beat. They assume that public knowledge of nuclear landscape stories is much bigger than it is. After five years of Trump and a year of pandemic, not that many people are thinking about nuclear waste stories or nuclear treaty withdrawals or accelerating arsenals in China or continued testing in North Korea. Knowledge of these issues is not as widespread as you would think so you bring a story to an editor who covers nukes stories and he or she might say the broad strokes of these stories are already known. No, they’re absolutely not.

The nuclear landscape has changed dramatically over 76 years but today the average person still doesn’t know much about nuclear weapons or imagines they’re too technical or theoretical to understand. How do you impactfully cover something that people view as this scary invisible thing they feel they have no control over?

In 1945, when the atomic bombs were first set off and the government was tasked with explaining these new weapons, the vast majority of people would never be able to grasp the concept of how atomic weaponry worked, the physics behind the weapons. Also, any time there’s this enormous scale of casualties, the human brain just can’t wrap around that level of destruction. So initially, getting people to comprehend not only the scale of destruction, but what it portended for humankind was a challenge that every media outlet failed to achieve until Hersey came along. He provided an instructive but complicated to implement example in that you always have to find a way to bring it back to the human level.

Another thing that journalists face now is “existential threat fatigue.” We’re coming out of a global pandemic. We’re really wrestling with climate change. How much more can we take? Well guess what — we don’t have the luxury of exhaustion. Journalists are again tasked with making people care about one more thing that is enormously consequential in their lives and doing it in a granular sort of way.

In January, the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons entered into force. Under the “ban treaty,” the development, testing, production, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, use or threat to use nuclear weapons is illegal. How should journalists be covering the treaty and discrepancy between those nations that have adopted it and those that reject it?

Well maybe we should be covering it period, like at all. It shouldn’t be page A16 material, it should be page A1 material. I think the general awareness of this is probably close to nil. The fact is that most people don’t realize the enormous discrepancy and also frankly the powerlessness of the treaty that has all of those signatories and the enormous disproportion of power that is given to nuclear powers.

If you want to make people care about it… and understand the significance of treaty coverage, you have to bring it back to “how does it affect you and your family”? There really needs to be a more immersive environment for this kind of storytelling.

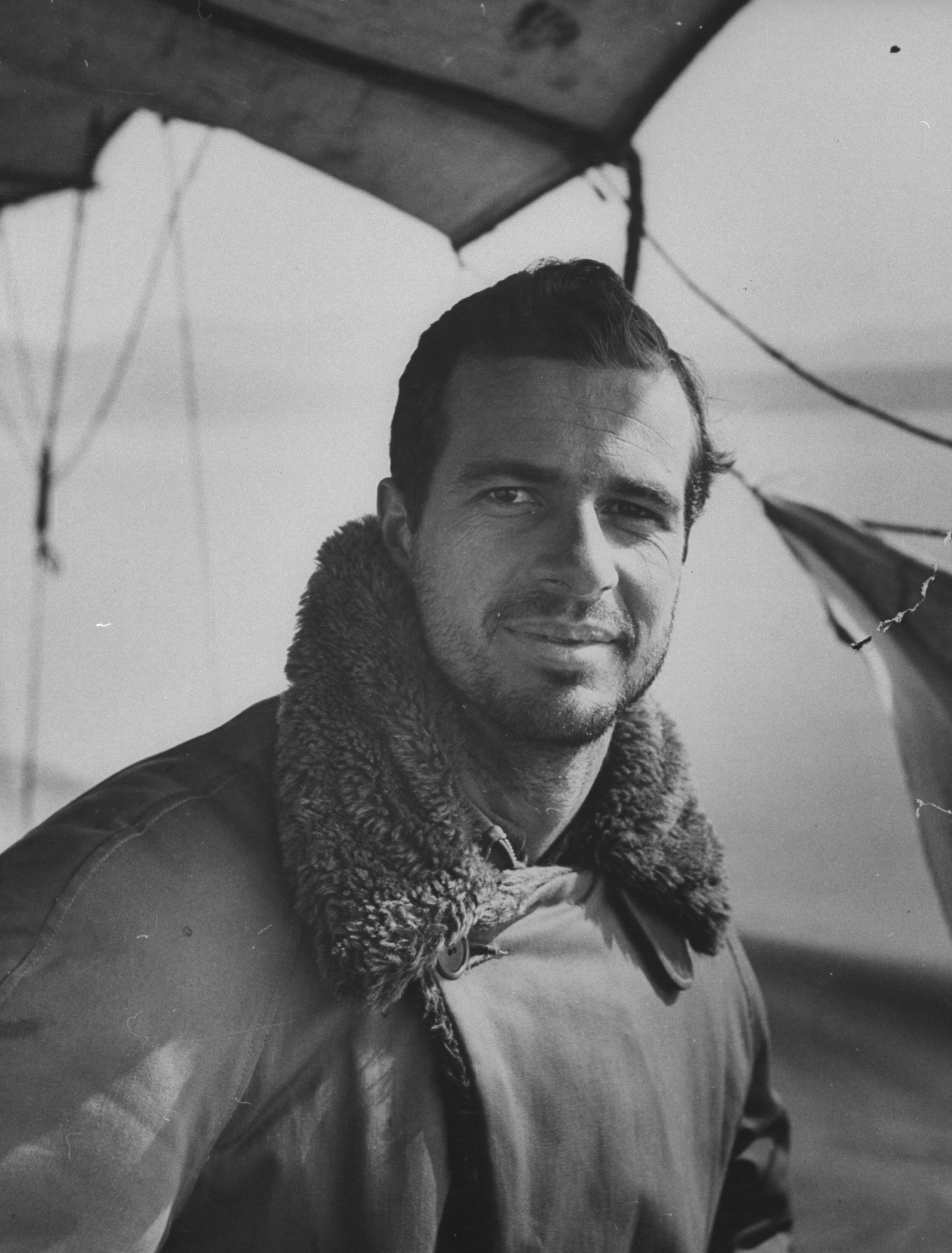

Writer John Hersey sitting at his desk in office at TIME. (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

In “Fallout” you described how as fatality numbers get higher and higher — the human mind shuts it down, because it’s beyond our comprehension. Do you think the same is true when you talk about nuclear spending?

You get statistic stupor when it comes to mass casualty or spending statistics. In talking about the gazillion dollar proposed nuclear modernization budget, imagine what else could be done with that money. Imagine what $1.7 trillion looks like when applied to infrastructure. Imagine $1.7 trillion applied to education. You have a totally new country.

With Hersey’s reporting on Hiroshima, reporters had reported the story of Hiroshima before him. They’d all reported that the bomb was the equivalent of 20,000 tons of TNT and that around 65,000 buildings had been destroyed upon detonation. People were like, “oh, that’s terrible,” and then had totally forgotten about it. It took Hersey to put it in the human context.

Can you talk about the importance of the timing of your book about Hersey’s coverage of the atomic bomb?

[It] became urgent because we had to release it for the 75th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also because we had just entered into the official Trump era and suddenly my entire community of fellow reporters was being called “enemies of the people.” This was a story that had to come out fast to show how essential reporting is to democracy, to the individual, and to the common good. Not just in a nebulous fourth estate sort of way but in a “if not for this one reporter, we might have had nuclear war” sort of way.But as memory of those testimonies recede — memory of what nuclear war really looks like and what it really does to human beings — we lose the potency of work like “Hiroshima” as a deterrent.

Climate change has taken decades and years to manifest. COVID-19 took months and weeks to spread around the world. With nuclear weapons, something very bad could happen very fast and in minutes or hours we’d be in a completely different world.

See, people think that’s hyperbole, but it’s not. It’s 100% accurate and the fact is that experts were sounding the alarm about a potential global pandemic for many years and they were alternately embraced and ignored. Climate change experts were sounding the alarm for decades and now we’re living with that. Well guess what, nuclear experts are sounding the same alarm — it couldn’t be louder or clearer. [They’re] just not getting the media attention that they should. The fact is, we have been culturally hyper-aware of the nuclear threat and we could be again.

Now we’re in what experts deem to be a worse place than the 1950s, 60s or 80s. Cultural awareness seems to be at an all-time low. It doesn’t just fall to the media to raise awareness. It falls to the entertainment industry to help raise awareness in a responsible way. It falls to schools. It falls to political leaders to really start staring this down. It’s not just about activists and journalists creating awareness. It has to be part of popular culture also. That’s a huge generator of awareness. I don’t want to sound like a Cassandra in eyeliner here but what will it take to create the urgency? Usually it takes a scare.

We can’t afford for that to happen. Last summer Indian and Chinese soldiers were fighting each other with rocks at the border in Ladakh. China and India, India and Pakistan, North Korea, the Taiwan Straits — these nuclear flashpoints are this close.

Take Pakistan and India. The crassest American contingent would say, “ok, fine, let them nuke each other.” It just shows a grotesque lack of understanding of these weapons. It’s not just lack of understanding among the general population, there’s now a lack of institutional knowledge even in our own Congress. It hasn’t been a predominant issue for them for a long time so there’s not a great deal of institutional knowledge or great awareness of threat. The challenge of raising awareness is staggering. Once you’re aware of these issues and once you’re aware of the threat, exhaustion is not an option. The only option is tenacity.

Lesley Blume’s comments were edited for length. Cover photo by Photo by Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images. All photos, including those of Miss Toshiko Sasaki and Dr. Terufumi Sasaki (above), appear in the book, “Fallout.”

Jon Letman is a Hawaii-based independent journalist covering people, politics, and the environment in the Asia-Pacific region.

“Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World” comes out in paperback on August 10.

Correction issued 8/6: In a previous version of this article, our editors incorrectly attributed a quote to the book, “Fallout,” from the book, “Hiroshima.” The text has been edited to reflect the correct quote.