Late last year, as losses mounted in Ukraine’s failed summer offensive, a drama of death and solemn religious duty unfolded in an isolated Muslim community in Ukraine. Drohobych is a small city 31 miles from the Polish border, far off the beaten track of Ukraine’s Islamic culture. There are around half a million Muslims in Ukraine, mostly in the east and south, but only 100 live in this nondescript provincial town.

Yet late on an October evening the office of Ukraine’s chief Muslim military chaplain got on the phone to Drohobych’s imam. Junior Lieutenant Muhammad Ali, a military chaplain who works for one of the country’s most prominent clerics, had an urgent request: Drive some 186 miles south to Berehove, an even smaller town in the Transcarpathia Province. Go to the local military hospital. Prepare the body of combat medic, Samad Minorov, for burial.

Ali himself had only discovered Minorov’s Muslim background the day before. One of Minorov’s relatives, who had fled to western Europe in the war’s early days, had called to say that the soldier needed an Islamic burial. This was news not only to Ali, as a representative of Ukraine’s office of Muslim military chaplains, but to the entire military administration. Although Minorov had been a medic for years, he had never told anyone about his faith.

With no information to go on, the military had defaulted to a standard funeral service. “If I didn’t find someone to prepare his body,” Ali explained by phone from his Kyiv office, “tomorrow he [would] be buried like everyone, like a regular Ukrainian, like a Christian.”

Muslim chaplains like Muhammad Ali face distinctive challenges as a religious minority in the Ukrainian military. Ukraine’s military has fewer than 200 full-time Christian religious leaders in service. Most of these are Orthodox Christian priests in this Orthodox-majority country, but there are only five Muslim chaplains.

Muslim chaplains feel a special obligation to support Muslim soldiers — not only by organizing last rites but also by advocating for Muslim soldiers’ needs to Ukraine’s military administration. However, some soldiers like Minorov choose to keep their religious identity to themselves.

Despite Ukraine’s efforts to professionalize the military chaplaincy, when Muslim soldiers don’t disclose their faith, it makes the job of the Muslim chaplain not only complicated but occasionally urgent. As in Minorov’s case, chaplains are forced to make funeral arrangements on short notice in far-flung locales, all to fulfill one of their faith’s most solemn obligations.

Ukraine’s Muslim Soldiers

Ukrainian Muslims are a diverse community of converts, indigenous groups, and immigrants. There are an estimated 500,000 Muslims in Ukraine. Sunnis and Shia from central Asian countries moved to cities during the Soviet period. Around 250,000 Tatars, a Turkic group of Muslims who converted in the 14th century, claim the Black Sea Crimean Peninsula as their homeland.

Ukraine’s military has always had Muslim soldiers, but they began joining in greater numbers after Russia annexed the Crimean Tatar homeland in 2014.

Said Ismagilov, one of Ukraine’s most prominent Muslim leaders, was the mufti of an umbrella Muslim organization in 2015 when the government took the first steps to meet these soldiers’ religious needs. According to Ismagilov, Ukrainian Muslim leaders had to work from scratch to figure out what to do. “We did not have any suitable model from Muslim countries, [so] we looked at how Christians in Ukraine do it and adapted this practice to the needs of Islam,” he said.

At the time, Muslim soldiers were spread thin in Ukraine’s military, with maybe only three or four serving in a single unit. It was impossible for Muslim chaplains to be permanently in one place or stationed with one unit, Ismagilov explained. Instead, Muslim chaplains traveled up and down the frontlines. They stopped in units where they knew Muslim soldiers had been posted, relying on the soldiers themselves to identify themselves.

The number of Muslim chaplains has remained the same since 2015; there are five clerics serving the entire military. While the ranks of Muslim soldiers have grown dramatically after Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, there are no Muslim-only units. Muslim soldiers are scattered along a frontline that stretches some 620 miles.

“In such conditions, it is difficult to organize Friday or holiday prayers,” Ismagilov said.“ The imam-chaplain conducts individual meetings and prayers with small groups of Muslims.”

He added, “The entire activity of a Muslim chaplain in Ukraine is movement between positions to meet with Muslims.”

Advocacy

Nowadays, years after the military commissioned the first Muslim chaplains, not even Imam Marad Putilin, who heads up the Muslim section of the Department of Military Chaplaincy, can say exactly how many Muslims soldiers are fighting for Ukraine. Putilin, who converted as a young adult in Kharkiv, worked with Ismagilov to set up the Muslim chaplaincy. Although he is a prominent military official, he does not hold back from advocating for Muslim soldiers’ needs, even in interviews with Ukrainian news outlets.

In a November 2022 interview with the Religious Information Service of Ukraine, Putilin complained that the government was failing to record soldiers’ religion. Entire battalions of Muslim soldiers had joined since Russia’s full-scale invasion, he said, adding: “I can only note that now it has become much larger than in 2015 and other years when the fighting was only in the Donbas.”

While government record-keeping is a problem, according to Putilin, soldiers themselves have various reasons for keeping their faith to themselves. Many Crimean Tatars hide their identities because they have relatives behind Russian lines. Other Muslims simply feel faith isn’t important. They grew up in secular households during the Soviet period, for example, when the state discouraged religious faith of all kinds.

Still others are worried they’ll be excluded from the military’s macho esprit de corps. In a September 2021 interview with the Religion In Ukraine news service, Putilin told a story about meeting a Muslim soldier who kept his faith a secret from his frontline unit. Asked why, according to Putilin the young man explained, “You know, here with the guys I smoke, and I can get drunk, and eat all sorts of things. I don’t tell anyone that I’m Muslim.”

Many faith traditions discourage smoking and drinking, and Christian soldiers who follow rules about a healthier lifestyle could also be ostracized. Nevertheless, it’s widely acknowledged, even among Ukrainian Muslims with no official connections to the military, that Muslim soldiers keep quiet about their identity.

An NGO worker I met at the Drohobych Islamic community center, Viacheslav Mysko, recounted a story about one soldier, a personal friend, who hides his identity with a nickname. The soldier uses the Slavic-sounding Vasya. His real name is Vahid, a version of the Arabic name Wahid. “There are a lot of Muslims who are fighting,” Mysko said, “but few know that they are Muslim.”

Changing Attitudes

According to Muslim military chaplain Oleg Chanturia, these attitudes are changing. Now that Russian forces are on the offensive, with drones flying overhead, soldiers routinely face the risk of death and deal with extremes of stress and anxiety. Muslims, like their comrades, are turning to faith. Chanturia himself conducted our interview from an underground bunker; for security reasons, he couldn’t reveal his location, but he was confident that as a chaplain he was making a positive difference for Ukrainian society. “In Ukraine, religious belief is alive and progressing,” Chanturia said.

There are a lot of Muslims who are fighting, but few know that they are Muslim.

– Viacheslav Mysko

With Muslim chaplains stretched so thin, local imams and Muslim community leaders regularly step in to provide for soldiers’ needs, and not only by welcoming them to Friday prayers. They also help meet soldiers’ material needs, sending care packages of halal food to the front lines. A system of rules called halal dictate not only what Muslims may eat (no pork, for example) but also how that food is prepared. (Halal makes provisions for the humane treatment of animals, for example).

Putilin has been complaining since 2015 about military food, speaking in interviews with Ukrainian journalists. In his 2021 interview with Religion In Ukraine, he said that local imams still send meat, stew, sausage, and canned goods to the front, because Ukraine has not yet figured out how to provide soldiers with food they can eat that will also allow them to adhere to their religious tradition.

“Nothing Yet”

For his part, Muhammad Ali echoed Putilin’s complaints. “It’s still in progress, still nothing yet,” he said. But halal rules also provide for exceptions under extreme circumstances, including war. “Maybe if it were peacetime, the army could make some changes,” he explained, “but we’re in a battle for the existence of our country.”

When a Muslim soldier dies, chaplains work with the soldiers’ family on funeral services. If the family says the soldier was a Muslim, the administration will call in Ali, Putilin, or someone else.

But that isn’t always an easy task. The massive displacement following the 2022 invasion has made it difficult to contact some soldiers’ families. In some cases, it’s impossible, especially when the family has settled in Europe or further abroad.

Before he was drafted Minorov had lived in Berehove, a small town in western Ukraine with no mosque and no organized Muslim community. Although Minorov’s remains were in Berehove, there was no imam close by to prepare the body for burial.

To solve these problems and make good on their duties, chaplains like Ali are learning about new Islamic communities in places like Drohobych, and forging ties with the local imams who are putting down roots as refugees.

“You Have to Help”

In Drohobych, Imam Abdurahman Islyamov led me on a tour through the city’s Islamic community center on a Friday afternoon. Islyamov, a Crimean Tatar, moved here with his family in 2014. They were the only Muslims for hundreds of miles. Eventually, he persuaded friends and relatives to join them. By 2018, the community was big enough that they asked Drohobych’s government for a space to hold Friday prayers, and the mayor donated an unused downtown office building.

After the prayer service in the second-floor prayer hall, Islyamov led me into a side office to meet with community leaders, including the NGO worker Viacheslav Mysko, who is also from Crimea. While Ukrainian Muslims are a small minority, the two men had never met Ali before his phone call. This is not surprising, since Muslims live throughout the country, and Crimean Tatars like Islyamov and Mysko have their own leadership and organizations.

Ali grew up in Kharkiv, more than 620 miles from Islyamov’s hometown on the Crimean Peninsula. Ali’s father was Syrian, so he belongs to the umbrella group representing Muslims who immigrated to Ukraine. Crimean Tatars belong to an organization called the Mejlis, with its own religious and political leadership.

According to Ismagilov, the former politician, relations between Crimean Tatars and other Muslims are good. Top-level officials coordinate when there is a need to represent Muslims’ needs to Ukrainian government officials, he explained. However, this kind of coordination was new at this lower level of Ukrainian Muslim life.

Although Ali was a stranger to Islyamov, the imam snapped into action at Ali’s request for help. He reached out to Mysko who was in Lithuania picking up a shipment of humanitarian aid. Mysko has friends in Transcarpathia’s military administration, so he contacted the hospital holding Minorov’s body. Meanwhile, Islyamov called around to shops. Maybe someone could open up their store so he could buy the necessary materials.

Mysko underscored the urgency: “We didn’t know [Minorov] personally, but it doesn’t matter. You have to help. And if you don’t try to help, it’s considered a sin.”

Working with Ali on funerals is not only about supporting the military, but also a way to do one’s religious duty. “We have to do it,” Islyamov added, “And if we have to, then we put effort into it, because we are responsible for it before God.”

In the end, an imam from Lviv arrived in Berehove before Islyamov. While Islyamov had been rushing to gather supplies, Ali had called someone else who had what he needed on hand. Nevertheless, both men were pleased simply that duty had been done.

“It was not done by our hands,” Islyamov explained, “but we are satisfied that the obligation was fulfilled.”

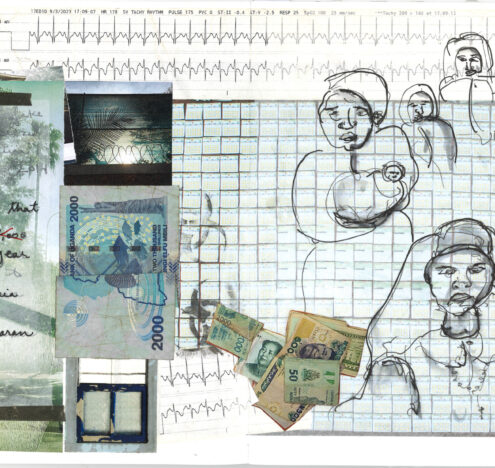

Commemorating the Fallen

Military service, especially during war, often helps diverse societies discover a national common cause. The same goes for chaplains who are finding themselves thrown together with religious colleagues they would not have met otherwise. Christian military chaplains I interviewed spoke mostly about discovering what they had in common with Christian colleagues from the country’s distant and unfamiliar regions. Sometimes for the first time, at military training sessions evangelical Baptist pastors from Transcarpathia are sitting next to Greek Catholics priests from Lviv and Orthodox priests from Kharkiv.

The case of Samad Minorov’s burial shows how Ukrainian Muslim military chaplains are going through this same process of discovery and unification within their own religious community. Ukraine’s Muslim chaplains, even in these urgent circumstances, were able to arrange for Minorov’s body to be prepared according to Islamic tradition.

Muslim officials at the highest levels of the Ukrainian military now have the occasion to meet and collaborate with local leaders throughout the country, including imams like Islyamov as he works to integrate his community into their new home in Drohobych, far from their Crimean homeland and Ukraine’s historic hubs of Islamic culture.

After the interview, Mysko offered me a ride in his sedan. Snow had started to fall in the gray dusk. For a while, the traffic flowed easily on the two-lane road out of town, until we came to a stationary line of cars. We pulled into the line and waited, curious about the cause of the traffic jam, until I heard Mysko say, “Look there!”

Coming toward us, on the other side, an Orthodox priest in a long black cassock was holding up a heavy metal cross. A step behind, a woman grasped an ornate picture frame. I looked at the photo as she approached Mysko’s door. It was dark, but I caught a glimpse of green fatigues. Suddenly, the line of some 15 people following behind made sense: a soldier’s funeral.

As the war presses on, there will be more of these solemn processions on the streets of Ukrainian cities. No matter what direction the fighting takes next, there will be more opportunities to commemorate soldiers who lost their lives in the fight.

Besides sacrifice on the battlefield, these funerals also speak to the religious dedication of Ukraine’s military chaplains. For the Muslim community, it is not just commissioned officers helping bury the deceased. Local imams, people like Abdurahman Islyamov, also pitch in when needed. Meanwhile, as more Muslims sign up for the fight, Putilin said, “This cooperation means serving both God and Ukraine.”