“and a mute sadness settles in,

Like dust, for the long, long haul. But if

I do not get up and dance again,

The savages will win.”

Sam Hamill, The New York Poem

Yassin Mohamed, a Cairo-based artist, spent almost four years in Egyptian prisons for participating in political protests during the revolution. While imprisoned, Yassin produced a series of sketches and paintings that chronicled his life behind bars.

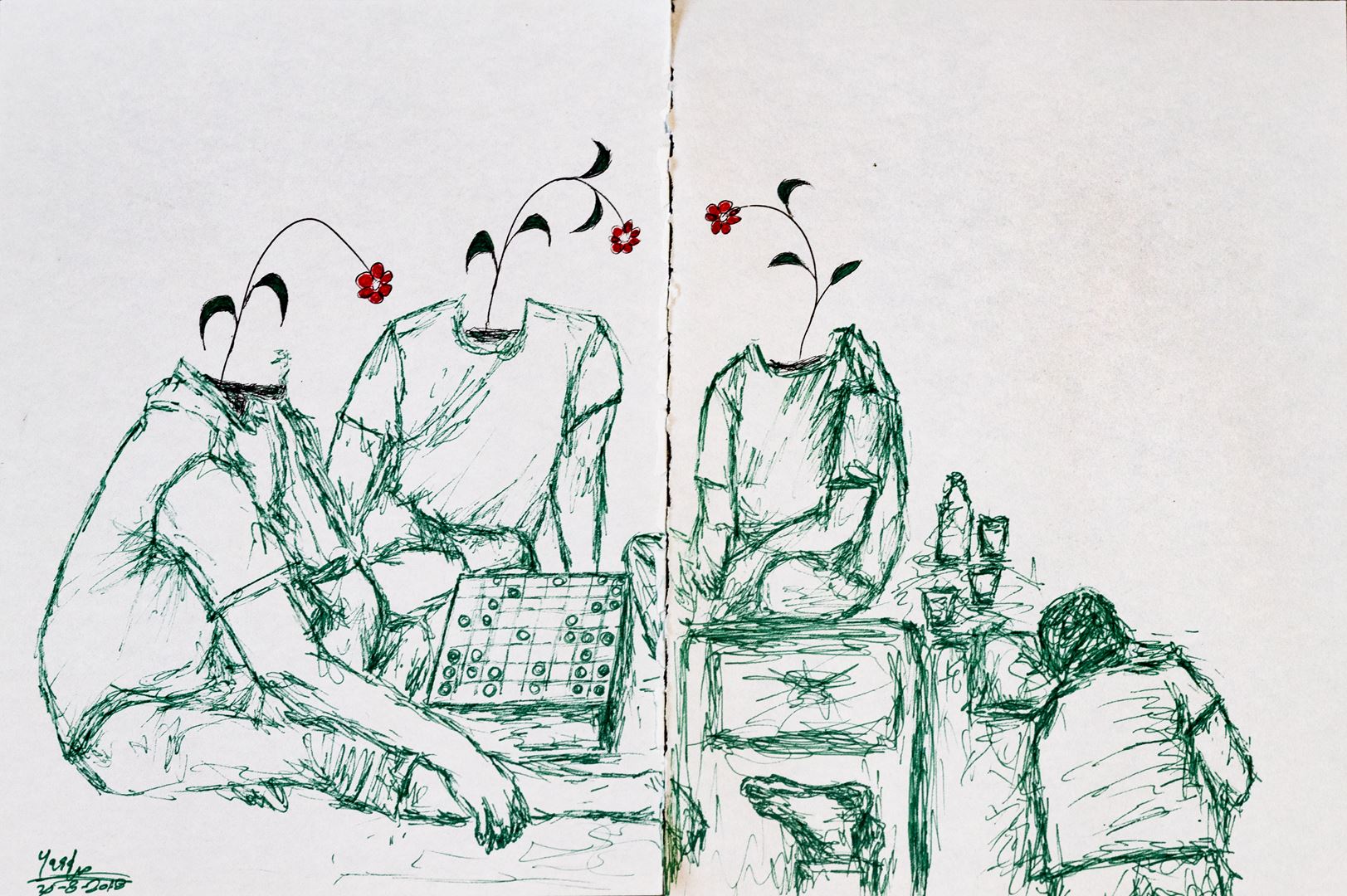

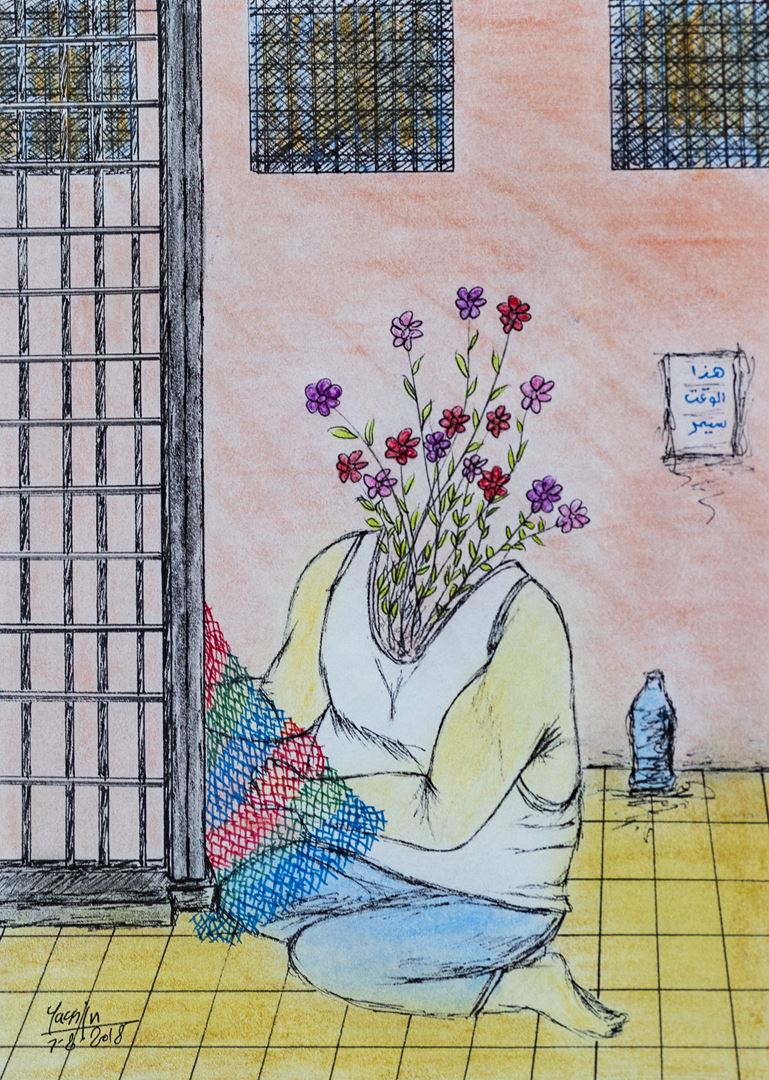

Using ink pens and a sketchbook, the supplies he managed to acquire within the maximum security prison, Yassin documented everything from the physical space to the collective nature of incarceration: A communal bathroom adorned with roses given to a prisoner by his wife on their wedding anniversary and signs instructing inmates to “please leave the bathroom the way you would like to find it”; A group of prisoners playing chess or cutting onions together.

However, Yassin’s sketches depicting the seemingly mundane and even the beauty in the banality, are starkly juxtaposed with his works of individual pain and isolation. His pieces such as “Hiding from Loved Ones” and “What No One Sees” depict harrowing scenes of intimacy that feel intrusive to witness. Through his art, Yassin bestows upon us a rare glimpse of what life is like “on the inside.”

Four of Yassin’s works are featured in our curatorial project, “A Prison, a Prisoner, and a Prison Guard:” An Exploration of Carcerality in the MENA Region. The exhibition explores the impact of prisons on countries and communities across the MENA region through “prison art.” Included are works that not only depict the literal experiences of carcerality, but also ones that reaffirm beauty and life in the face of such barbaric and savage systems — Yassin’s works do just that.

In April of 2024, we had the privilege of speaking with Yassin Mohamed through a video call, where he shared more about his experience in prison, the context for the pieces we feature in the exhibition, and his artistic journey.

*

Who is Yassin?

I chose the name Yassin Mohamed in 2008. I am from a village in Al Qanatir, Egypt, but left home when I was fairly young. When I left my village, I was homeless for a long time, then started working in an ice cream shop.

Once the revolutions started there were a lot of things happening in Cairo. I participated in the revolution and drew what was happening around me. At times I helped provide emergency first-aid care to the injured protesters. Even though I am not a doctor or work in medicine, there are things that are important to know for times of intense police or military clashes.

I was imprisoned in 2013 in what was known as the “Shura Council” case, where we participated in a peaceful protest in front of the Shura Council. The state ruled that I would be imprisoned for 15 years for participating in the protests, then reduced my sentence to three years, of which I served one year before I was released.

I was then imprisoned a second time in the “Talaat Harb Events” case where I was sentenced to two years in prison on account of participating in a protest on January 8 2014 in Talaat Harb Square. Here, I was sentenced for two years and I served them all.

All together I spent about three and a half years in prison.

In all my imprisonments I used to draw things about my life in prison. I would draw my fellow inmates, because it used to pass the time. I used to draw what was happening in the cell around me. How I lived, how I ate, how I drank. Just my life. It was like my diary, but instead of writing it, I would draw it.

I was released on September 21, 2018, my birthday. After my release, I decided that I would dedicate myself to improving my art. I started studying art more. I learned artistic techniques and different schools of art. For the next five years I poured myself into this study. It was this focus that helped me move past and heal the trauma of my imprisonment. I would try to cure my trauma through art. Whenever I would feel horrible, or feel the inhumanity or gravity of my experiences, I would just draw…

I drew whatever I wanted, the positive and the negative, whatever I was feeling.

I left prison with a lot of anger and a myriad of other negative thoughts. Drawing helped me overcome this trauma. When you leave prison you often feel as though your thoughts are an illusion, and that the people around you are strange to you. Like you are living in a different world. You are just trying to make it to the next day. During this time, drawing helped me cope. It was like a friend to me. Every time I felt bored or anything, I would draw.

Drawing changed everything for me.

When did you start identifying as an artist?

I still don’t. I still feel like I have a lot of learning to do. There is a continuous learning aspect to it, there is always something more.

I started drawing when I was six years old. But I didn’t know the details of what it took to be an “artist.” I didn’t introduce myself or conceptualize myself as an artist. It wasn’t until 2018 that people started recognizing my work and liking aspects of my artistic technique and style, but I was still just a painter.

What is the process of creating art in prison?

Imagine that someone locks you in a room, an ordinary room, for two days. There may be things in this room that can entertain you, maybe a sketchbook, maybe something else. After the reality of your confinement catches up to you and the boredom sets in, you’ll look for anything to do. Here you’ll find that your creativity and imagination work better.

As I started drawing more and more, I would take my sketches and smuggle them out of prison in food containers that I would give to my friends to take to my family to keep safe.

Drawing in prison is very different from outside of prison, because it’s a closed space. There is nothing you can do to change your mood. Prison is all waiting. You just sit around waiting and waiting. Time has to pass somehow, and one of those things that used to pass the time was drawing. But outside of prison there are an infinite amount of things to do to pass the time.

Now that I’m free, it’s harder to draw. There are so many things I could be doing at any given time. Sometimes I cancel gatherings, I cancel travel, a lot of things, just so I can sit and draw. I try to recreate that confinement and solitude for myself. The prison is what draws out the imagination, but outside of prison, you’re surrounded by everything.