In a suburb of Lomé, Togo, the house was cloaked in wet leaves from a storm the night before. When I arrived in the afternoon, military police had already forced entry and customs agents were starting to carry boxes to the idling trucks lined up on the quiet street outside. In the house, the walls of the entire downstairs were lined with boxes destined for the market in Lomé. Opening one, I saw it was full of small packets, 2 pills in each. “Raging Bull” was printed on the side with a picture of a white woman locked in an embrace with a well-endowed black man, her head thrown back.

I had spent that morning photographing a group of police and Interpol agents as they broke into a locked pharmacy kiosk. Around noon, back at the police station, there was a feeling of tension.

“Where is the rest of the team?” I asked. The lead agent from Interpol said they had gone to a house where there was a big stock of fake Viagra. “A group of Chinese nationals have locked themselves in and are refusing to come out.”

“I should be there, no?” I said.

He said the situation could degenerate; he mentioned my safety.

I said, “If it degenerates it’s better if we’re there.”

The Chinese men were expressionless as the agents hauled away their boxes of illicit sexual enhancement drugs and I photographed. In the upstairs bedrooms, agents inventoried computers, hard drives, cash, scales, and other equipment. There were chicken bones behind the bed and cigarette butts stubbed out on the floor and into the porcelain of the unflushed toilet and the sink, overflowing ashtrays and damp foam mattresses on cardboard on the floor. There were sealed plastic bags of jellied chicken legs. I concentrated on the photographic frame and not on my feelings of morbid fascination.

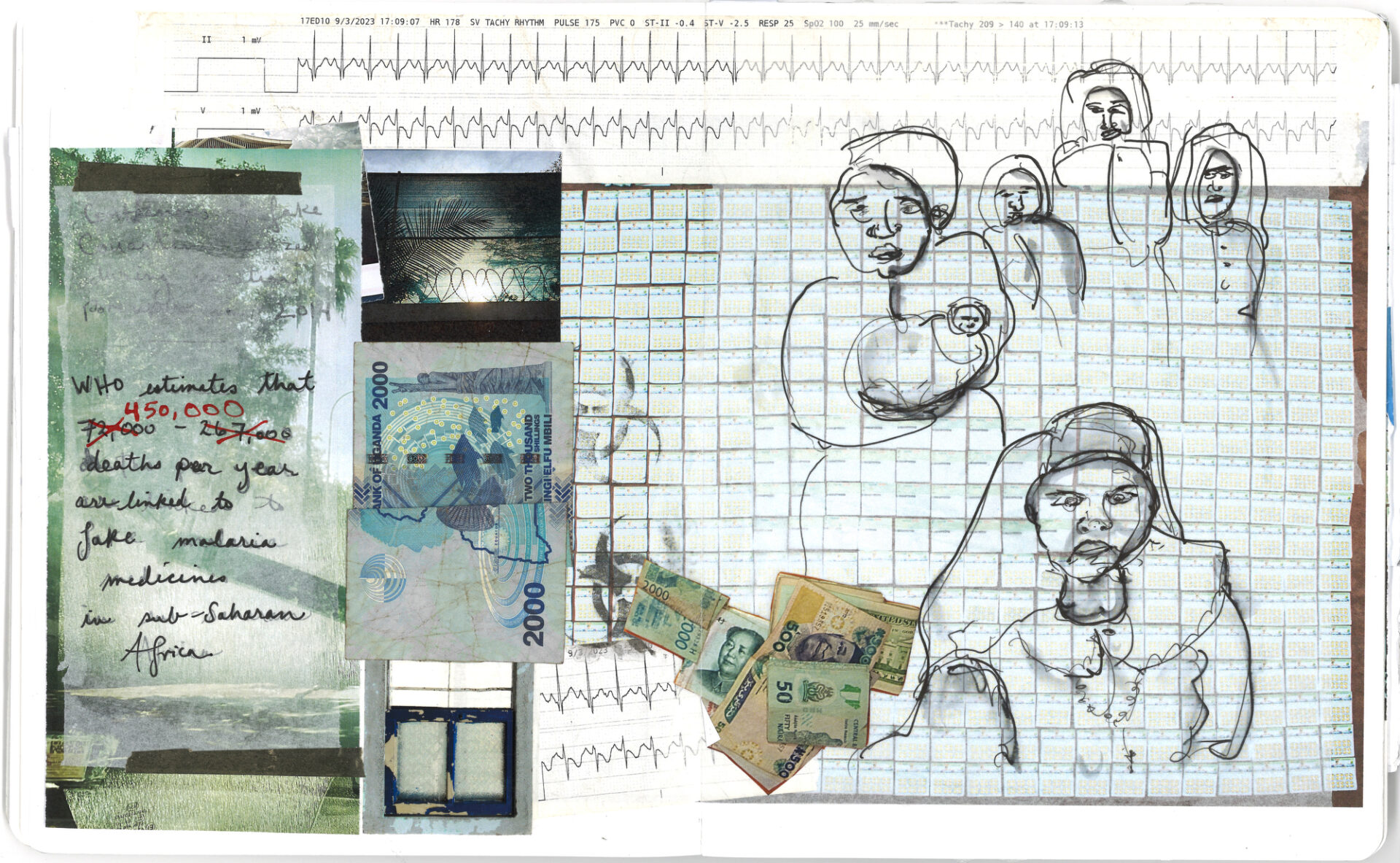

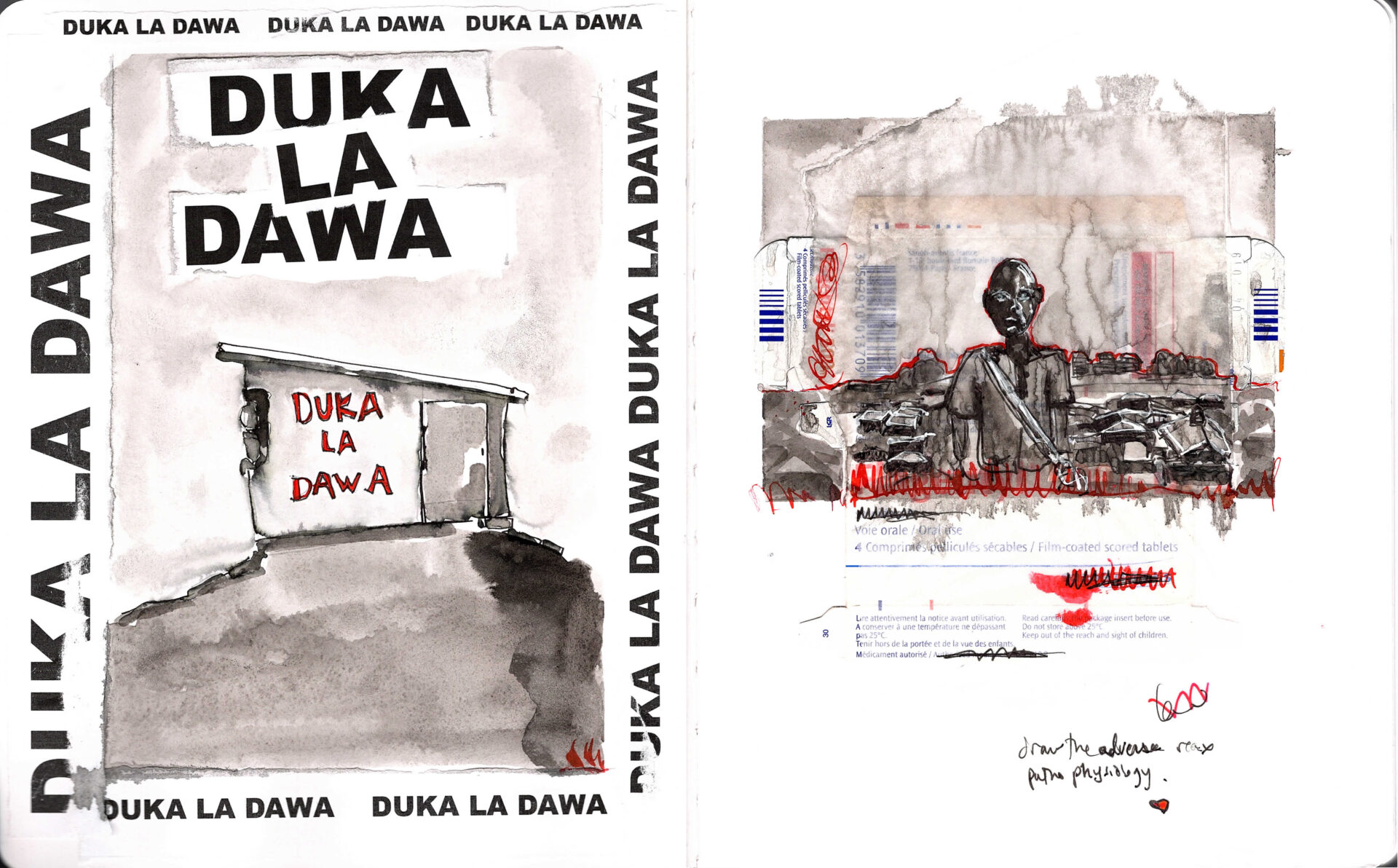

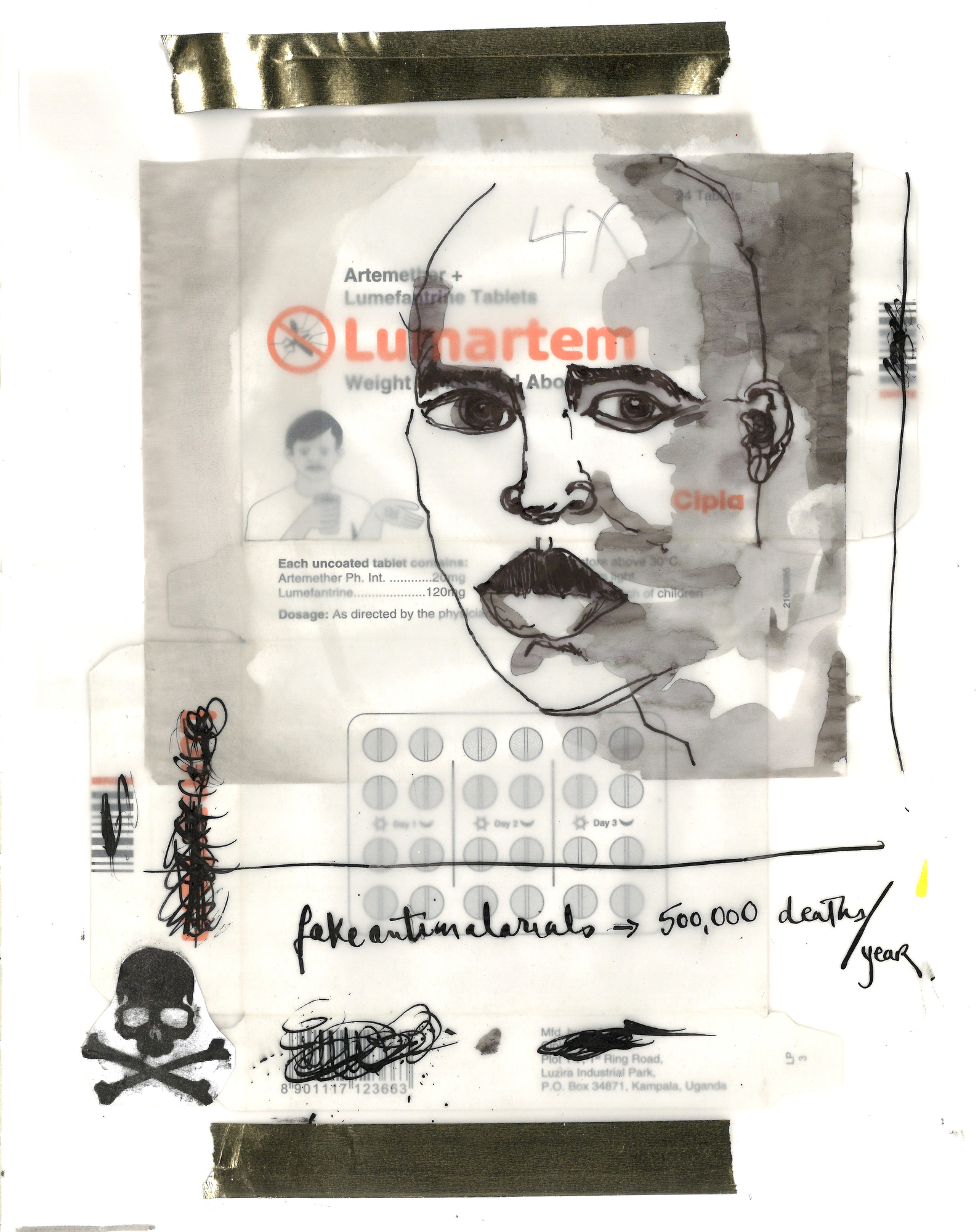

In May 2014, Interpol hired me to document Operation Porcupine, a multi-agency effort to track and seize counterfeit medicines and illicit products. As part of their Turn Back Crime initiative, the operation took place over one week across 6 countries in West Africa (Benin, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Togo) with Interpol agents, Togolese customs, military police, local police, health officials and representatives of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. In Togo, the Global Fund investigators were especially interested in recovering fake Coartem, the most available and well-known anti-malarial medicine in the region. A World Health Organization-commissioned report estimates that 72,000-267,000 deaths per year are linked to fake malaria medicines in sub-Saharan Africa alone, and 500,000 worldwide. In the Grand Marché, in a covert warehouse at the end of a long and twisting corridor, we found a cache of fake Coartem. The investigators showed me the minuscule discrepancy in the packaging; it’s almost impossible for the untrained eye to tell the difference between legitimate and counterfeit boxes of this critical medicine. Pharmaceutical companies create ever more complex holograms and other distinguishing marks to prove the veracity of their products, but counterfeiters are becoming more adroit at copying this packaging for their fake drugs. “They can copy a hologram within a month,” a Kenyan investigator told me.

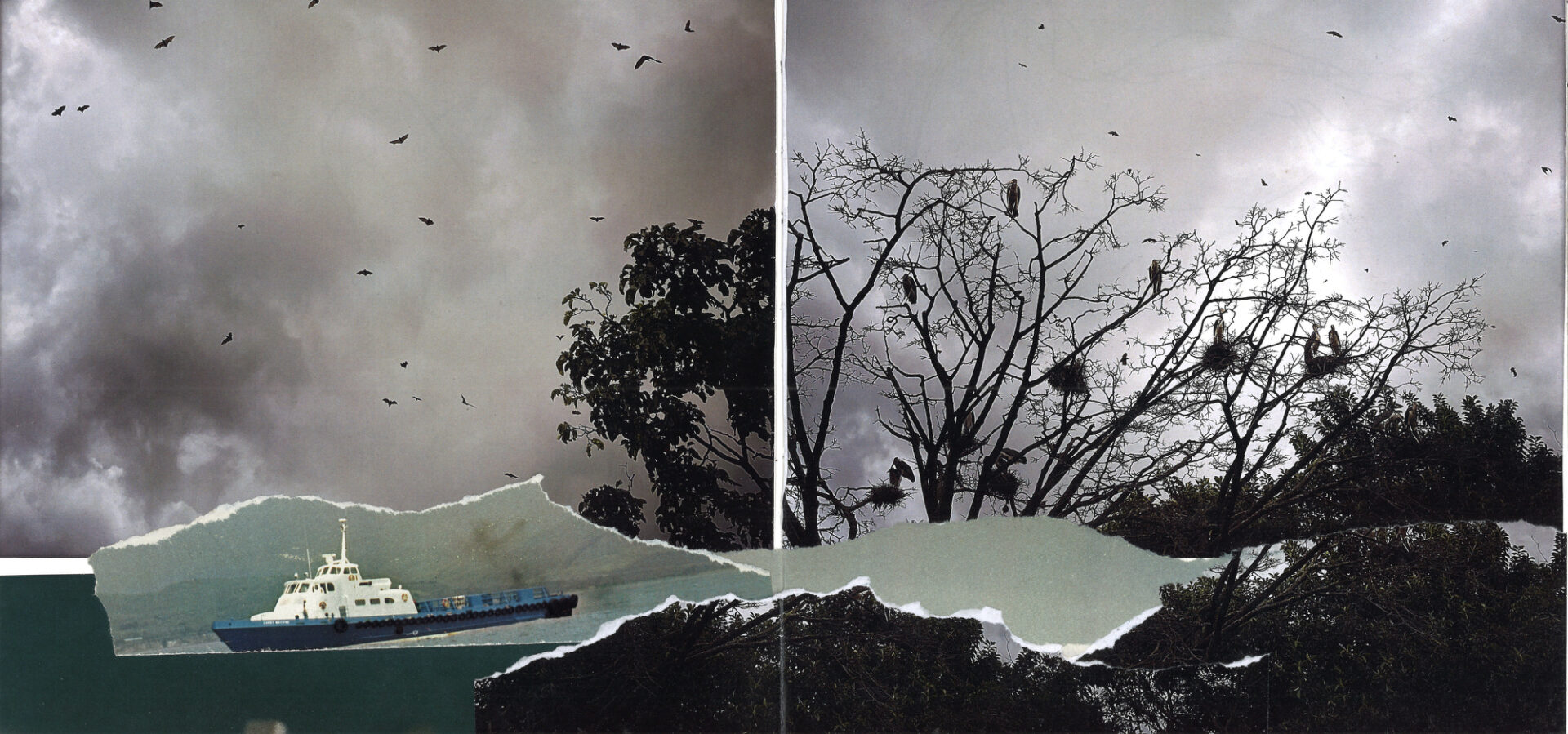

I’ve always been curious about who we are and why we do what we do. That ridealong with international cops in Lomé, Togo, was my introduction to the problem of counterfeit medicines, and the continuation of my unfurling lifelong questions about power dynamics, corruption and belief. The global trade in counterfeit medicines is worth approximately $200 – 432 billion per year. It is one of the fastest-growing criminal activities. Often manufactured in China or India, counterfeit medicines filter into the supply chain in sub-Saharan Africa, facilitated, Kenyan and Ugandan investigators I interviewed said, by corrupt officials at ports of entry: seaports, airports, overland border posts. Lacking protection, each nation’s border becomes porous, like a cell membrane, molecules (drugs, guns, people) diffusing across delicate tissue. Organized Crime Groups (OCGs), often with their own shipping companies, transport these fake drugs across the sea, according to Bongo Woodley, a Kenyan investigator. Efforts to deter them are undertaken by Interpol or local civil society groups, yet there isn’t much incentive to stop when the money to be made from counterfeits is far greater than the money to be made from narcotics. According to investigators, there is very little political will to stop the problem. This is because the market for fakes is vast, and there are fewer consequences if you are caught. Perhaps the Chinese nationals in the house in Lomé seemed unconcerned because they knew they’d be deported only to return in a few months with a new stock of fake Viagra.

The Road

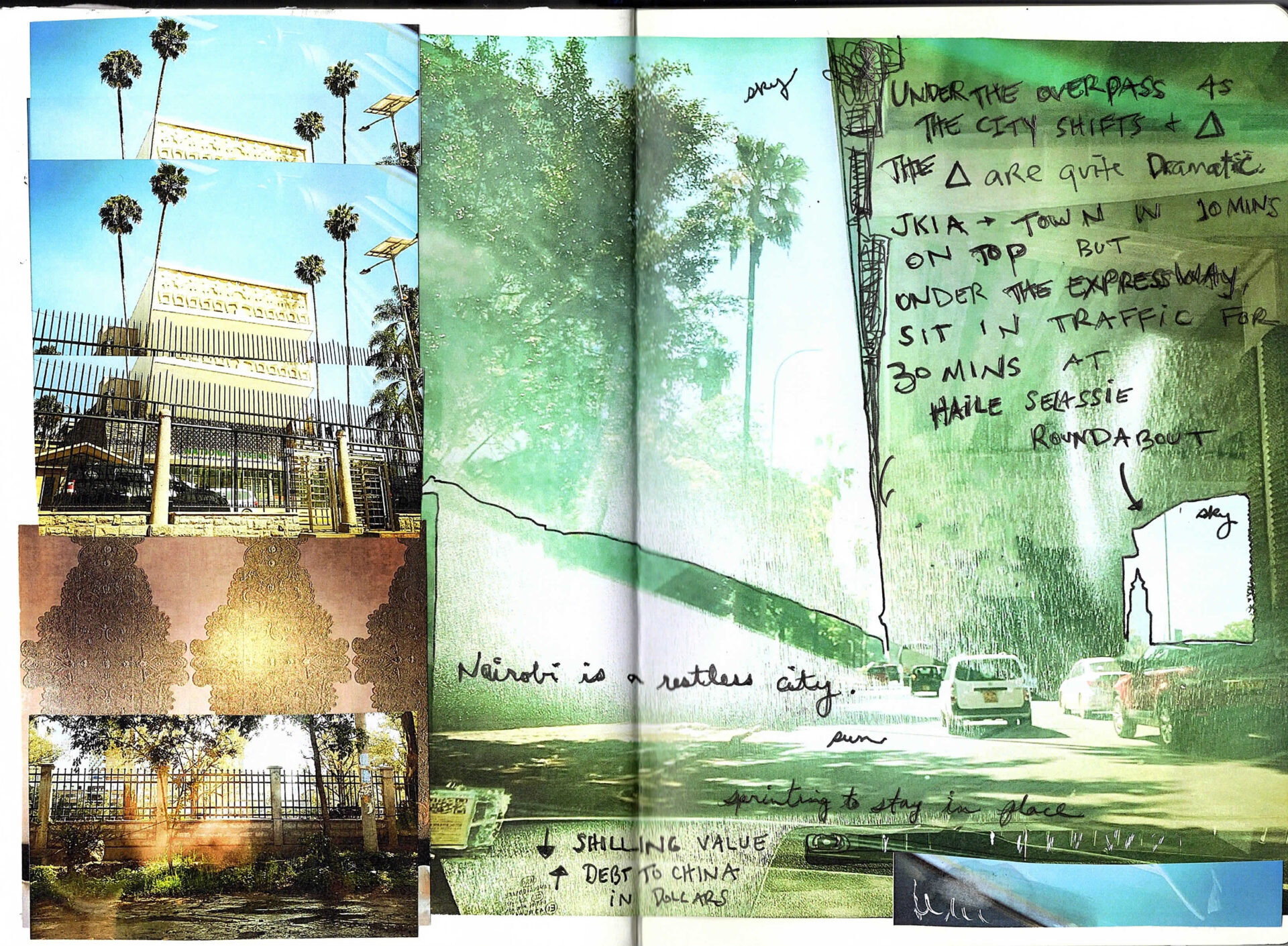

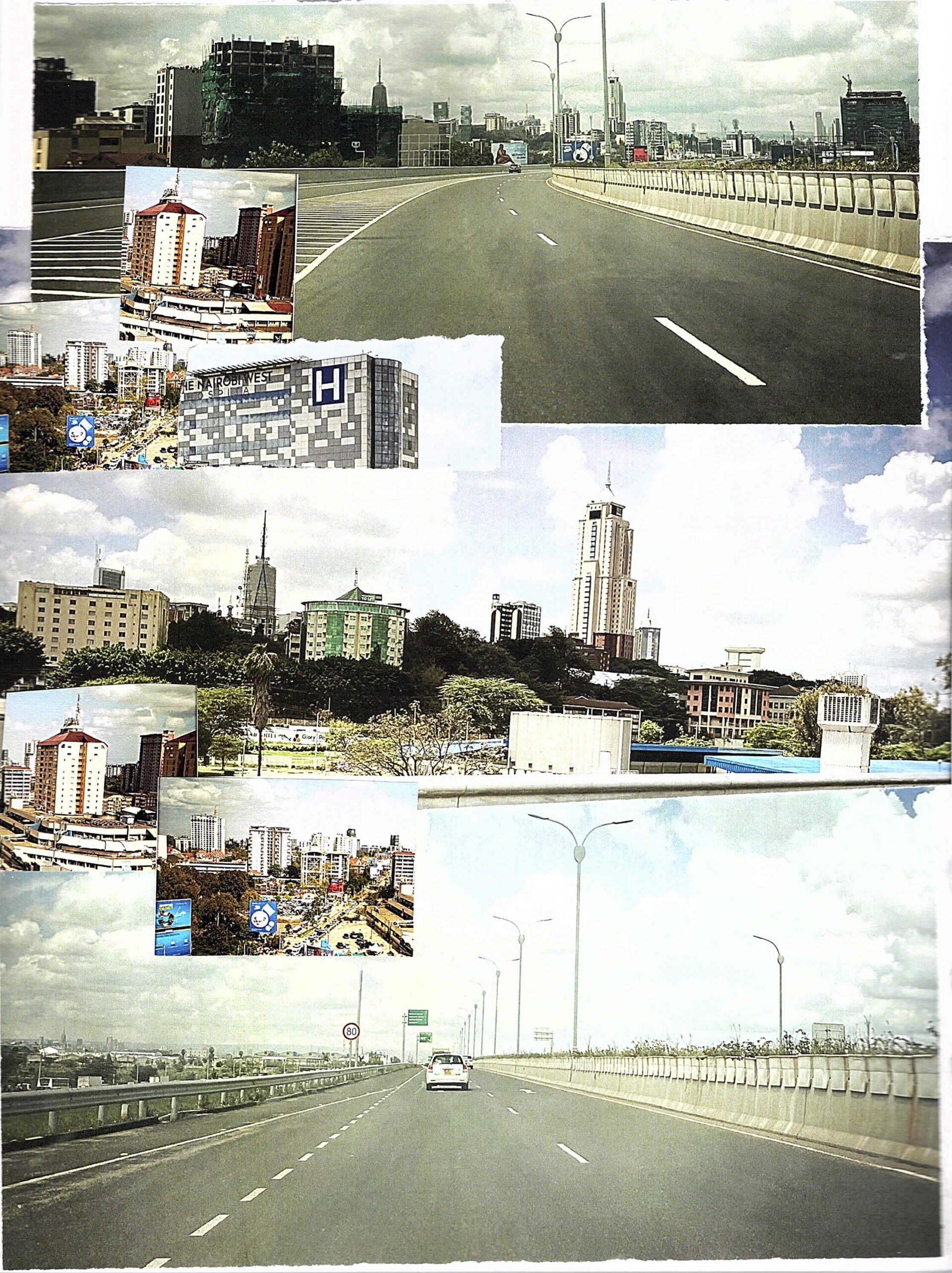

The story of fake drugs is the story of the road. The new Nairobi Expressway, fast and efficient, accelerates the transport of all goods, including fakes. In Ghostlines, Johannes Theodor Aalders writes that “infrastructure is an attempt to ‘tame and fix in place’ unruly and unstable movements, stressing the importance of stability a road promises.” (Here he draws from the work of Penny Harvey and Hannah Knox.)

On the new Nairobi Expressway, it’s 10 minutes from the international airport to town, 200-400 shillings ($1.75 – $3.75) for the toll. It can feel effortless, the way it’s possible to pay a toll and fly on an almost-empty road as smooth as ice, and avoid the hassles beneath the expressway: the crowded matatus and buses and cars jumbled and stalled, stuck, in bumper to bumper traffic, exhaust fumes filtering in through the windows.

Like much of the world, in Nairobi there is great speed and efficiency, a “frictionless” universe—coordinated by apps, held up by day labor—if you can pay for it. If not, under the expressway, traffic crawls. Aalders writes, quoting Charis Enns, “Africa’s new development corridors cannot be understood by considering only the movements they facilitate, but primarily also by the ‘emergent forms of spatial exclusion and immobility.’”

The promise of new infrastructure in the region leads to investment and the city transforms: excavations for foundations, endless construction, money-laundering empires. The enclosed garden bungalows with flame trees and bougainvilleas are razed for another faceless apartment/casino/office block. Nairobi is refaced and repurposed. Kenya’s debt to China skyrockets, with the construction of these skyscrapers, along with the Single Gauge Railway ($4 billion), the Expressway ($3.6 billion), and the port.

Like all cities, Nairobi is layered. There are many Nairobis. It is a restless city. The economic gap is in-your-face. With more resources, the wealthy can afford better health care and fly, if necessary, to South Africa, the UK or the UAE for surgery. The pharmacies with better regulation are in the richer areas. The poor are at a greater risk of taking a fake drug or using a substandard product. Unable to pay for bus fare, most people in Nairobi walk to and from work on broken roads, crowded with SUVs and cows. Uber drivers request cash payments; if too many clients pay with a credit card, they don’t have cash for fuel. In March, even the touted Expressway was stopped: severe heavy rains flooded it; the drainage system backed up, and cars swam in two feet of water. In “Ghostlines,” Aalders quotes Mimi Sheller, “‘clean, quick, ethereal mobility’ is an illusion and that ‘actual mobilities are full of friction, viscosity, stoppages, and power relations.’”

Corruption

The story of fake drugs is the story of power. And corruption.

In March this year, I went to Kampala, Uganda. In Kampala, fake drugs are sold in licensed and unlicensed pharmacies and open markets as well as the black market. According to Uganda’s National Drug Authority (NDA), the main problem is tampering, in which expired generic medicines are repackaged in new, up-to-date boxes. On March 8, the NDA completed a raid on a local medical supply company, arresting 11 individuals and seizing $100,000 worth of expired testing kits for malaria, HIV, and Hepatitis B, Abiaz Rwamwiri, the public relations manager for the National Drug Authority told me.

In Kampala, I met Fred Muwema, chair of the Anti-Counterfeit Network (ACN), a non-profit organization that approaches the issue of fake drugs with research, legal enforcement, and communication. He said fake drugs are an existential threat, and he spoke of soft power as a way to solve this problem. “The consumption of fakes is a mindset issue,” he said. It’s common for Ugandans to take potentially fake drugs from unlicensed places — those pills are more affordable and widely available in small medicine shops in rural areas and informal settlements. It’s more convenient to buy something close to home. Muwema said that the efforts to stop counterfeiting are not successful because the macro-view of the anti-counterfeit focus is on enforcement and they miss the root cause: the huge market for fake drugs. “So, if you close one shop, another opens. Our approach is a behavior change campaign,” he said. ACN is working with the Ugandan Parliament to pass the Anti-Counterfeit Goods bill. They are helping to draft the bill and complete it. ACN is developing a Track and Trace method and online portal where consumers can report adverse reactions. It is a central repository of information where, for example, mothers whose children get sick from fake drugs can report it. Or, as with antimalarials, they have a place to record that they aren’t improving with treatment.

In Kampala, I met an investigator with ACN who requested not to be named. We were in the car, windows up, AC on, going through the city, past the ministries on Nakasero Hill, traffic glare filtering through the tinted windows, as we talked. He said his work was difficult because of corruption within the police force. Often if another investigator brought a perpetrator into the police station for questioning, by the time he arrived to oversee the process, the perpetrator would already be gone. “He paid a bribe and left.” There are many roadblocks to justice, especially in the context of a country where the president, Yoweri Museveni, in office since 1986, had changed the constitution to raise the age limit so he could run for another term, and his security forces allegedly tortured and intimidated the main opposition candidate, Bobi Wine.

“Why do you do this work?” I asked. It seemed like all the old metaphors could apply here: Sisyphus, David/Goliath, Lilliputians holding the giant down with tiny stakes and string. I recalled what Muwema had said about the organized crime groups: they are protected by powerful people. “Even if a complaint is made, the case will be killed. People fear to speak,” he had said.

“I am passionate,” the investigator replied. “A counterfeit is against humanity and we are trying to protect humanity.”

“Are you at risk for the work you do?” Muwema had mentioned the danger of countering the counterfeiters: they’ll kill you.

“The counterfeiters threaten me.”

“How did you get involved? Is it personal?” I asked him.

It was when his brother had pancreatic cancer 10 years ago that the investigator realized the scope of the problem of counterfeit medicines. “Some local herbs doctor” had prescribed a fake chemotherapy medicine mixed with an herbal remedy. His brother died.

“So,” he said. “When it comes to fighting counterfeits, I go there all-heartedly.”

Muwema had said the counterfeiters were also victims, “victims of human greed.” Maybe there’s a way greed, or just the mere difficulty/impossibility of survival in a toxic end-stage capitalist world, hollows them out, and they are just reacting, running to stay in place. Maybe the effort it takes to survive disrupts growth and potential. Maybe corruption is the only way to survive.

Katherine Boo, in her book “Behind the Beautiful Forevers,” writes about corruption in India but her words apply to corruption in the rest of the world, too: “In the West, and among some in the Indian elite, this word, corruption, had purely negative connotations; it was seen as blocking India’s modern, global ambitions. But for the poor of a country where corruption thieved a great deal of opportunity, corruption was one of the genuine opportunities that remained.”

Desire

The story of fake drugs is the story of desire: to be well, to be fixed, to be thin, to feel better. And how that desire curls around belief. A pill is the material form where science and belief and desire converge. When I buy a pill for my pain I believe that it will work, that its source is pure, that it has the potential to heal me. Entelechy is the “potential of things to become themselves.” Entelechy is the oak inside the acorn. A fake drug is an empty pill, a hollow seed, no spark of oak inside its hull. A fake drug can be nontoxic, baking soda pressed into a pill shape, or it can be poisonous. In 2022, children in the Gambia drank Makoff baby cough syrup. Their parents believed it would soothe their coughs, heal their infections and make them feel better. It killed them. Four products, Makoff, Kofexmalin, Magrip, and Oral Promethazine, had filtered into pharmacies and markets in the country. The cough syrups contained high levels of diethylene glycol, a main ingredient in antifreeze, and 70 children and babies died, largely of acute kidney injury.

The Body

The story of fake drugs is a story of the body. And the cell. And water. The body is porous, influenceable, and the drugs are quick. The body is not just one thing and not separate from the environment. Everything filters through the body, as energy. We are water. The moon pulls on us as it tugs on the tides along the coasts of the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe. The body is “the ecotone where the weather of the future and the geographic conditions of the past converged to mold you into your unique form,” writes Sophie Strand.

The COVID pandemic weakened bodies, transformed lives and societies across the globe. Yet there were doubts about whether COVID was real, and false and misleading information spread quickly via the Internet. The cost of this misinformation campaign was more death and illness around the world, and also in East Africa, where the cloud of misinformation around COVID 19 meant many East Africans were taking the antimalarial hydroxychloroquine as a treatment, and often overdosing. An overdose of this drug can cause heart block, an interruption in the electrical conductivity of the heart, or seizures. The antidote is high-dose Valium.

According to the Interpol/ENACT report, COVID 19: Impact on Illicit Medicines in Africa, the pandemic led to an increase in demand for Tylenol and codeine-based cough syrups to soothe the pain of the symptoms; OCGs capitalized on this demand and upped their efforts to import fake drugs. The lack of inspection capacity at the Mombasa port (the main port of entry for fakes) facilitated these imports. The report goes on to say that misinformation about COVID (and a corollary erosion of trust in health systems and authorities) was spread via social media; therefore, the public was more willing to source drugs via illicit means. Furthermore, the report stressed that the demand for medicine to treat COVID led to an uptick in violence and “corruption-based attempts to access medicines intended for use in legitimate healthcare systems”; this led to an “increased risk of healthcare system failure and personal risk to healthcare workers.” As a global security issue, fake drugs reveal the cracks in the regulatory systems of each government and expose the insecurity of the supply chain. They also reveal the psychology of individuals and the eroding trust in government and authorities, as COVID misinformation has shown.

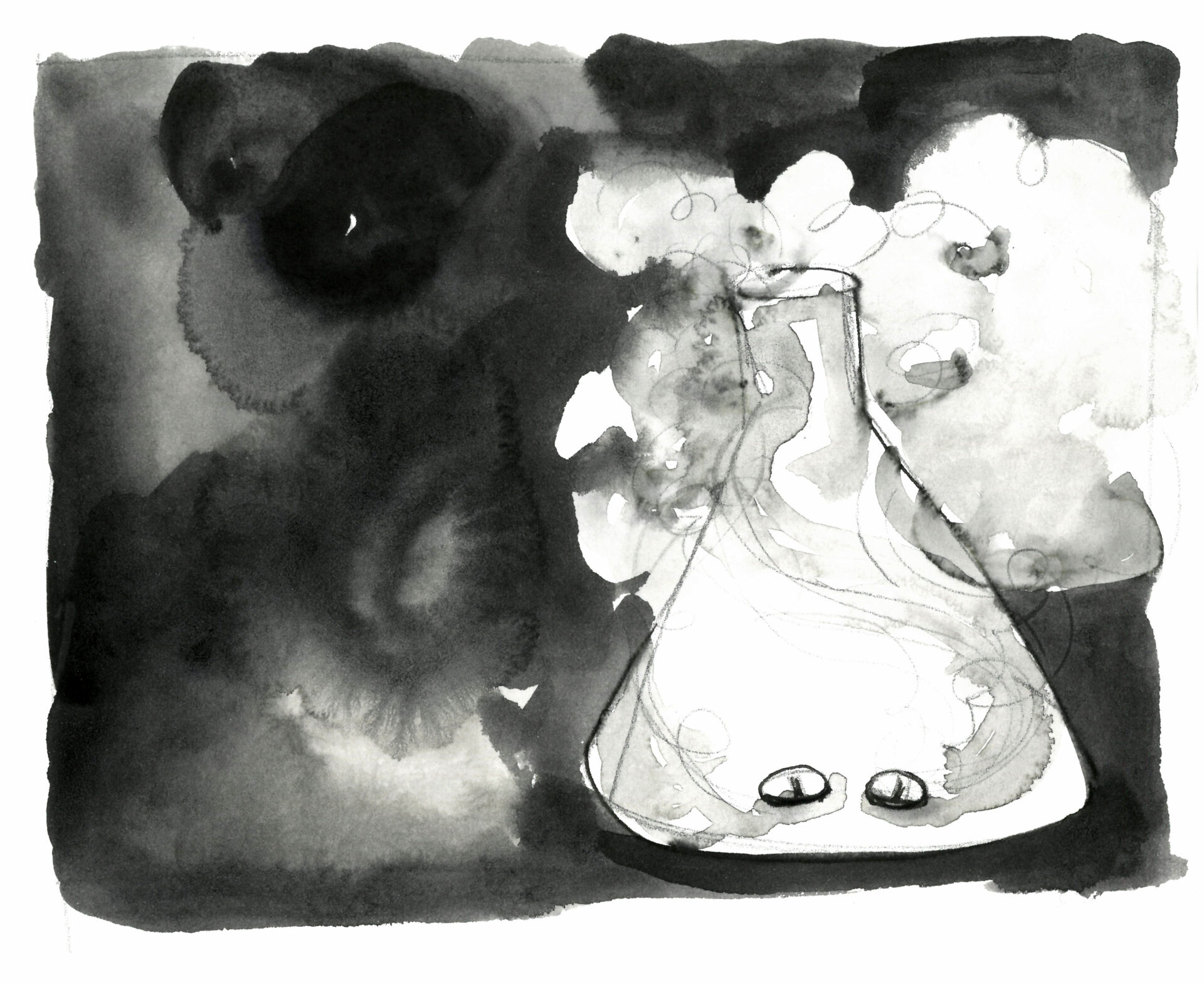

Testing

I visited two labs where medicines are tested. The quality control lab at NDA in Uganda and one at the Mission for Essential Drugs and Supplies (MEDS) in Nairobi, Kenya. MEDS is a faith-based, non-profit, WHO-approved medicine supplier started by nuns with Churches of Kenya. At MEDS there was a portrait of Sister Joan Devane, the Founder and first General Manager, on the wall next to a portrait of President William Ruto. The entranceway was decorated with a dry fountain with plastic gold trophies on the ledge. The lab manager Mildred Wanyama took me on a tour of the quality control lab, showing me how all the testing equipment worked and what it tested for. The lab at MEDS performs assays by liquid and gas chromatography, spectrophotometry, distillation and refluxing, PH. Their lab uses volumes of the US Pharmacopeia – National Formulary; it sets the standard for the contents of medicines: quantities and quality of active and inactive ingredients, and all specifications for the strength of the compounds, as well as labeling, packaging, and identifying medicines.

One of the main challenges to testing suspect medicines is cost. At the NDA, running all of the tests on one tablet of Tylenol costs $130. This is not affordable for small clinics in remote areas, which anyway don’t have the necessary equipment. But many fake pills are pressed from sodium bicarbonate, essentially baking soda, so a cheaper option is simple: the clinicians can test a pill by adding vinegar, and if the liquid bubbles, it’s not legitimate.

I’ve really only scratched the surface. In Kenya and Uganda the problem is diffuse; it’s difficult to pinpoint. Like trying to touch mercury, it slips away on contact. If there are adverse reactions, it’s difficult to know for sure if they are due to a fake drug or the disease process.

As a nurse, I know how critical it is for everyone to access safe and effective medicines. And to trust the person selling the medicine. Despite the controls and resources available to protect the drug supply in the United States, as the counterfeiters become ever more technologically advanced and savvy, counterfeit medicines are available there, too. A recent increase in demand for Ozempic, the diabetes medicine that is overused as a weight loss drug, has led to counterfeit versions entering circulation via direct-to-consumer websites and other unlicensed outlets. In December 2023, the FDA tracked and seized “thousands of units” of fake Ozempic. A recent alert regarding substandard Botox, the botulinum toxin in injectable aesthetic anti-aging procedures, led to individuals experiencing botulism-like illness — which has a risk of full paralysis and death. A patient at the ER where I worked in Pennsylvania had necrotic chemical burns under her fingernails from an Amazon-purchased, MadeInChina nail glue, an adjacent product that was cheaper but nearly identical to another product on the website. Many people know they are buying something substandard when they opt for the cheaper option; but rarely do they have the means to make it a proactive choice. Safety is expensive. Cheap fakes are deadly.

Hey there!

You made it to the bottom of the page! That means you must like what we do. In that case, can we ask for your help? Inkstick is changing the face of foreign policy, but we can’t do it without you. If our content is something that you’ve come to rely on, please make a tax-deductible donation today. Even $5 or $10 a month makes a huge difference. Together, we can tell the stories that need to be told.