As the right-wing meltdown over the caravan deepened in the fall of 2018, some Republicans began to blame prominent Jews for the crisis. Then US Representative Matt Gaetz posted a video on Twitter he claimed showed people handing out money to migrants in Honduras, questioning in the text of the post whether the Hungarian American philanthropist George Soros, who survived the Holocaust as a child, was bankrolling the caravan. Gaetz later admitted he’d mistaken the country — the video was from Guatemala — but his tweet had already reached millions of accounts. Among those who retweeted the post were Donald Trump, Jr., the president’s son, and several right-wing media figures with millions of followers online: the conspiracy theorist Jack Posobiec, longtime conservative commentator Ann Coulter, and frequent Fox guest Sarah Carter.

More dangerous yet, hardline white nationalists and others on the far right quickly answered the implicit call to arms baked into invasion rhetoric. Anti-immigrant militias from around the US flocked to the southern border. On Oct. 27, 2018, less than two weeks after Trump first called the caravan an invasion, a neo-Nazi gunman named Robert Bowers stormed the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and shot dead 11 Jewish worshippers. Bowers had previously complained on a far-right social media outlet that the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), a Jewish humanitarian organization, was responsible for bringing in “invaders that kill our people.” Around the same time, for nearly two weeks in late October and early November, a man named Cesar Sayoc mailed pipe bombs to several Democratic politicians — Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Hillary Clinton, among others — and Trump critics, including Holocaust survivor and liberal philanthropist George Soros.

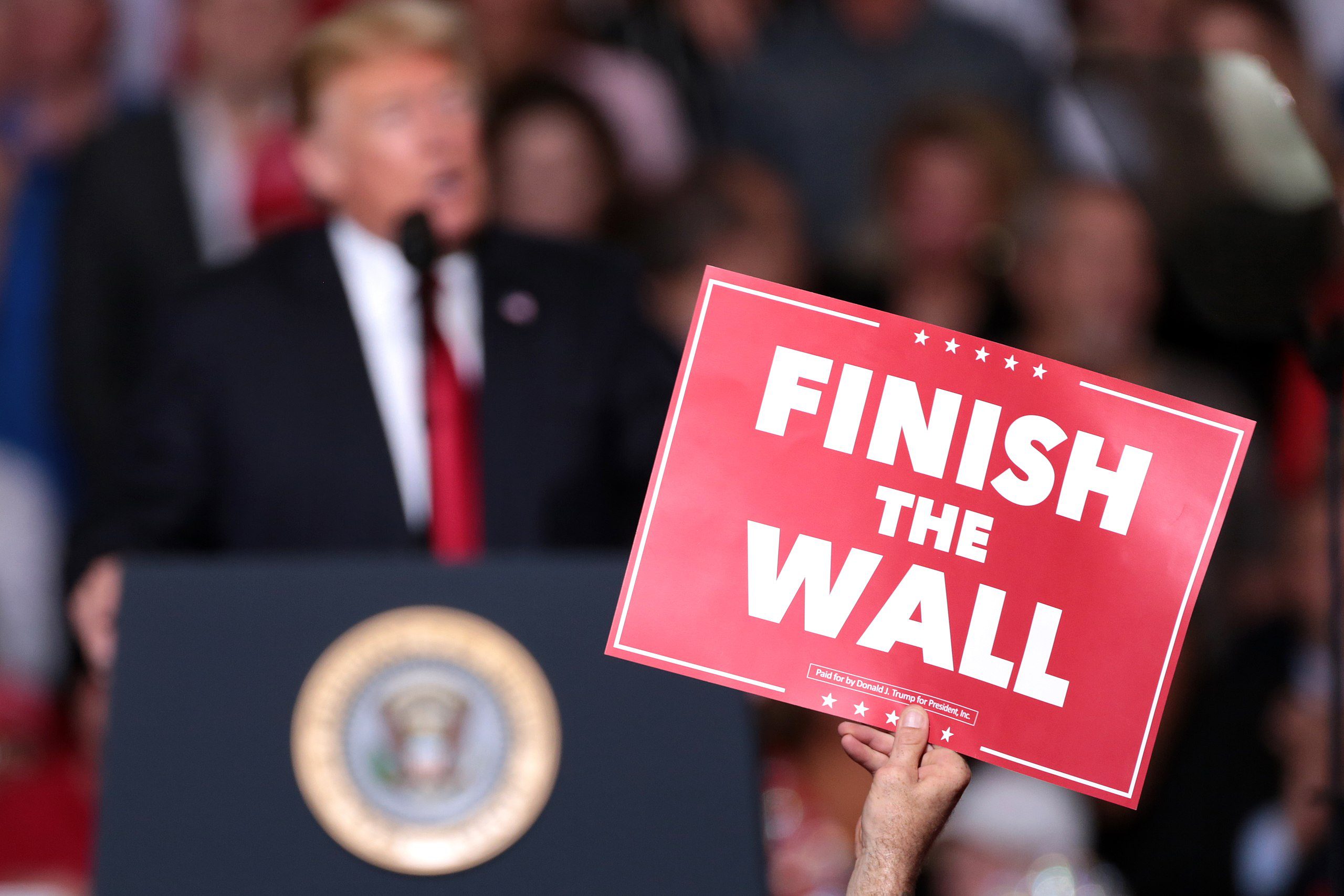

After the midterm election on Nov. 6, Fox and others apparently forgot about the caravan just as quickly as they had made it a central talking point. But the invasion rhetoric lived on, cropping up in both the US and distant parts of the world. In March 2019, New Zealand, a far-right shooter opened fire at a mosque and an Islamic center in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 51 people and leaving behind a manifesto that complained of the immigrant invasion. Five months later, a white nationalist fatally shot 23 shoppers in a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, to prevent what he called the “Hispanic invasion.” That year, in the first nine months alone, a Guardian analysis found at the time, Trump’s reelection campaign had already run more than 2,000 Facebook ads that characterized immigration as an invasion.

Shane Burley, author of Fascism Today and several other books about the far right, explained that there is “a direct line” between invasion rhetoric and right-wing violence. “There is a long history of portraying immigrants as a militant threat by framing immigration as invasion, to suggest that undocumented people are not just unlike us, but are foreign agents, a fifth column, or a sleeper cell waiting to destroy our way of life,” he said. “What this does is send a dog whistle for the more explicit white nationalists in [Trump’s] coalition to understand the claim in conspiratorial terms, and it also helps move his supporters past their own empathy and accept cruel and violent treatment of migrants as appropriate.”

By latching onto the invasion trope, Trump and his allies were tapping into a grim American tradition whose history predates and inspires modern iterations of both the white genocide myth and the great replacement theory. For some two centuries, invasion rhetoric has fueled nativist vigilantism and anti-immigrant state violence.

One of the early proponents of the invasion conspiracy theory was Samuel FB Morse, a prominent painter and inventor who contributed to the creation of the single-wire telegraph and Morse Code. A strict New England Puritan, Morse wrote a series of articles in 1834 that amounted to a blistering attack on Catholic immigration from Europe. Those articles were later collected and reprinted as the 1835 book The Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties of the United States. Writing under the pen name Brutus, Morse sounded the alarm on an “insidious invasion” through which the Catholic Church sought to infiltrate and destroy the United States. Without action to stop new arrivals, the country would soon fall “completely under the control of a foreign power.”

According to Morse’s argument, Catholics could never move past their supposed allegiance to the Vatican, and were unable to either understand or embrace the spirit of the American republic. As a solution, he proposed a melding of the Protestant church and the state and an overhaul of the country’s naturalization laws, which had produced “alarming evil.” The Catholic immigrants arriving in the country, in his words, were ignorant, indoctrinated, and neither loyal nor capable of loyalty to the United States. “At this moment the ocean swarms with ships crowded with this wretched population,” he wrote, “bearing them from misery abroad to misery here.”

Morse’s militant stance against Catholic immigration made him an easy fit for the Native American Party, for which his writing provided an intellectual basis. In 1836, Morse ran as a nativist candidate in the New York City mayoral elections and lost. The Native American Party was often referred to as the Know Nothings — if asked by an outsider about the group, a member was meant to reply only that they “knew nothing.” Between 1850 and 1855, the Know Nothings became the fastest-growing party in the United States, and by late 1854, the party had grown to more than a million members around the country. The Know Nothings’ rise led to both institutionalized discrimination and violence. In San Francisco, a party member who became a judge barred Chinese immigrants from testifying against white citizens in court. In Chicago, a Know Nothing mayor banned immigrants from city employment. In Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Louisville, and elsewhere, nativist propaganda against immigrant communities led to brutal attacks and deadly riots. Immigration, the party warned, was an assault on the country, and so-called native-born Americans had a duty to fight back. “Rise, brothers, spurn invasion,” went one of the party’s songs, “let’s die or save the nation.”

“At this moment the ocean swarms with ships crowded with this wretched population, bearing them from misery abroad to misery here.” – Samuel FB Morse

Summing up the Know Nothings’ success and tactics, the scholar A. Charlee Carlson has argued that the party erected a vast conspiracy “along traditional lines” to turn Americans against the notion that the country welcomed the world’s destitute. “An evil force was threatening to subvert the values of the United States, its agents had been detected, and brave heroes were needed to crush the threat,” Carlson wrote. “The nativist version cast Catholics and immigrants as the villains and American voters as the heroes. The Know-Nothings were masterful at turning this basic plotline into a compelling drama.”

The invasion theme saturated much of the country’s anti-immigrant sentiment throughout the remainder of the 19th century. In the 1870s, for instance, California newspapers made a habit of running panicked headlines about a so-called “Chinese invasion.” Sinophobic media coverage continued at a steady clip for years, eventually feeding the nativist rage that led to deadly anti-Chinese pogroms like the three-day riots that killed four people in San Francisco in 1877.

Reece Jones, a geographer and author of several books about borders, documented the intense campaign of discrimination Chinese immigration during the second half of the 19th century in his 2021 book White Borders. After years of hysteria that framed Chinese immigration constituted an “invasion” and an effort to turn the West into a “Chinese colony,” Jones wrote, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese laborers from immigrating to the country for 10 years, becoming the first piece of legislation that openly cited race and nationality to restrict immigration.

Even as the 19th century came to an end, the invasion trope — and the state repression and anti-immigrant violence it fueled — proved remarkably resilient.

In the early 20th century, several popular books likened immigration to an invasion. Journalist and statistician Frank Julian Warne’s The Immigrant Invasion, published in 1913, blamed foreign-born newcomers for much of the country’s problems, reserving special ire for Slavs and Italians. In contrast to the supposed “invasions of other centuries and of other countries,” Warne argued, “the present-day immigration to the United States is not by organized armies coming to conquer by the sword.” He went on to later decry that “the foreign-born element has already entered into the racial strain of the native population.”

Three years later, the conservationist Madison Grant released The Passing of the Great Race: Or, a Racial Basis for European History, an exhaustive, pseudoscientific tome that, in part, frames the history of human movement as a series of invasions. In writing the book, Grant hoped to make the case against non-Nordic immigration to the United States. Grant’s Passing of the Great Race became a foundational text for white supremacists and eugenicists, years later even prompting German Nazi leader Adolf Hitler to write the author a fawning letter describing the book as his “Bible.”