On free afternoons, I write movies about the Middle East. Particularly, the Middle East as it existed more than a thousand years ago. From noble princes to sprawling deserts, historical epics can capture a sense of wonder that is refreshingly distant from the Middle East’s contemporary traumas. They also, however, cast light on chapters of our shared history that are too often forgotten.

The white supremacist that murdered fifty Muslims in New Zealand also wanted to talk about history. He inscribed on his weapons the dates of major historical battles where Muslim armies clashed with Christian ones. In his manifesto, he explained that a desire for “revenge against Islam for 1300 years of war and devastation” partly inspired him to rip fearless Naeem Rashid, kind Daoud Nabi, little Mucad Ibrahim and so many others from their families.

As New Zealand mourns, we must re-commit ourselves to confronting the endemic anti-Muslim hatred and Islamophobia sweeping the globe. Our own government’s behavior in the United States is a vital piece of this discussion. But we must also address the “othering” of Muslims that predates 2016 or 2001 and dig down into the underlying narratives that nourish this hatred. This includes the proliferation of a historical narrative of “Western civilization” that excludes Muslims – one the shooter believed and one perpetuated by the erasure of Islam in American history classes nationwide.

By-and-large, the history of Islam and the Middle East is set apart — not a separate chapter, but a separate curriculum entirely.

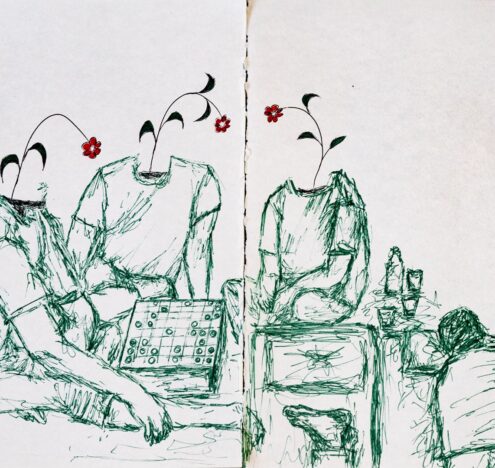

If your public school education was anything like mine, you were taught a story of ancient history that began with the glories of Greece and Rome, muddled through the Dark Ages, then revived itself in the Renaissance and an Age of Exploration that eventually led to the so-called “discovery” of the Americas. Maybe a footnote or a paragraph mentioned scholars in the Islamic empires translated Greek and Roman texts and helped reintroduce that knowledge into Europe, but by-and-large, the history of Islam and the Middle East is set apart — not a separate chapter, but a separate curriculum entirely.

The Eurocentric historical narrative that joins the United States with classical Greece and Rome — a link clearly illustrated by the neoclassical architecture in Washington, DC — is artificial. History’s threads are more tangled than a binary clash of civilizations. Yet, if we buy into this mythical narrative of Western civilization, we must acknowledge that it includes Islam. The scholars of the Islamic Golden Age collected, translated, and cultivated the work of Aristotle and other classical theorists. And the Middle East wasn’t just a bookshelf for classical knowledge — Muslim scholars made their own contributions, from pushing towards a heliocentric model of the universe, debating classical theories, to making significant medical advancements. On the road from Greco-Roman civilization to the United States, the Islamic Empires were an important stop.

The Orientalist project in the Middle East, as it was in Asia, that divorced Muslims from “Western civilization” was designed to justify colonization and subjugation — to make Muslims seem distant, inferior, dangerous, and barbaric. The Orientalist language used to describe Muslims has been normalized in the mainstream media. This “othering” language exists even in seemingly benign phrases like “Muslim world” or “Islamic world” that are not just useless for describing a faith with more than a billion adherents living across the globe but also automatically set Muslims apart from a “Western world,” as if Muslims float about on some nearby planet, tossing down the occasional kebab or classical book.

The fact is, Arab and Islamic history is “Western” history. Greek and Roman texts had margins annotated in Arabic. A Muslim slave explored the Americas on a Portuguese expedition centuries before the United States was conceived. And once the United States came into being, African Muslims arrived in the hulls of slave ships and helped build this country. From the coffee shops you sit in, to the algebra you endured in school, Islam has been part of this country’s fabric for centuries.

What message do we send our children when we teach the “Dark Ages” during the Islamic Golden Age? What message do we send Muslim children about their place in the United States when we erase the contributions of Muslims? Bringing Islam into American history curriculums won’t solve anti-Muslim hatred, but it could help shatter the Orientalist myth of “otherness” surrounding Islam in mainstream discourse and begin combatting the fundamental lack of understanding of Islam in the United States. It’s past time to radically decolonize our understanding of history and teach upcoming generations that Muslims are a part of this country’s past, present, and future. As the massacre in Christchurch showed us, the stakes are far too high to fail to act.

Laila Ujayli is a Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellow at Win Without War. She specializes in the human impact of US foreign policy in the Middle East. Follow her on Twitter @lailaujayli.