When Joy Ebube learned from a WhatsApp group chat that her former high school classmate Nabeeha Al-Kadriyar was kidnapped in Abuja, she found it hard to believe.

Ebube and Al-Kadriyar were not only classmates but also roommates at the Government Girls Secondary School in Dutse, a suburb in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. Although they graduated from secondary school in 2017, they remained in touch through the WhatsApp group created by their graduating set.

Ebube hoped that Al-Kadriyar would be released. But her prayers were never answered.

Al-Kadriyar, a 21-year-old university student, her father, and five sisters were abducted by gunmen from their home in the Bwari area of Abuja, on Jan. 2, 2024. Two police officers and Nabeeha’s uncle were killed when the police initiated a rescue operation at the scene.

The abductors relocated the victims to an undisclosed location and released Nabeeha’s father, Mansoor Al-Kadriyar, directing him to gather a 60 million naira (approximately $66,000) ransom for the release of the captive girls.

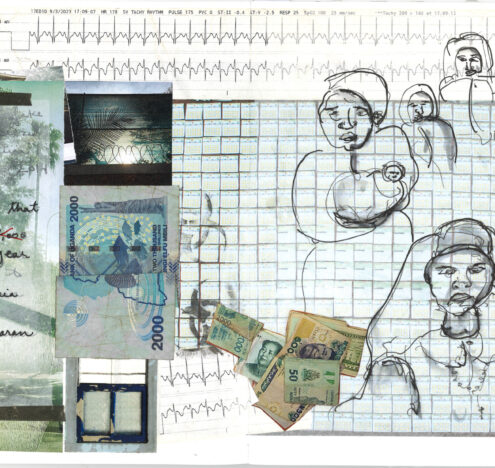

Nigerian law prohibits the payment of ransom, with a penalty of at least 15 years of imprisonment. But Mansoor’s family crowdfunded to raise the ransom money on social media. As the Jan. 12 deadline approached and only about half of the ransom was raised, the kidnappers killed Nabeeha Al-Kadriyar as a warning and increased the ransom amount to 100 million naira ($100,000).

The news of the young girl’s death broke Ebube’s heart. She said the deceased was a very bright student at school. “I cried. I told my mom, and I kept saying ‘they murdered her?’ It was so painful,” she told Inkstick.

Nigeria’s Kidnapping Crisis

Nabeeha Al-Kadriyar’s abduction and murder ignited widespread outrage in the country. Nigerians have taken to social media to express concern about escalating insecurity. Nigerians have long questioned the effectiveness of the country’s intelligence gathering and criticized the perceived failure of various security agencies in addressing insecurity.

There have been many kidnapping cases recently, including that of 13-year-old Folorunsho Ariyo, the daughter of the chief legal officer of the National Universities Commission, who was kidnapped and subsequently killed when her family failed to raise the amount of money requested for her release.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu condemned the killings and kidnappings only in response to public outrage. Following a security briefing, security agencies promised to combat the situation, mirroring decisions taken previously, which yielded few positive results.

Kidnapping for ransom is prevalent in Nigeria, with criminal groups snatching their victims from highways, communities, houses, and schools. The West African nation experiences one of the highest rates of kidnapping for ransom globally. Between July 2022 and June 2023, no fewer than 3,495 people were abducted in 582 incidents across the country, according to a report by the Lagos-based risk consultancy SBM Intelligence. Over $18 million was paid as ransom for victims abducted between 2011 and 2020.

Abductions for ransom surged in Nigeria in the late 1990s amid the crisis in the oil-rich Niger Delta, orchestrated by militants as a pressure tactic to address government negligence regarding oil pollution in their communities. Expatriates working for multinational oil giants were the primary targets.

The West African nation experiences one of the highest rates of kidnapping for ransom globally.

In an effort to combat the issue, the Nigerian government initially offered amnesty to militants in 2009, resulting in a decline in crime rates. However, with changes in government, the amnesty program faltered, leading to a resurgence of abductions and sea piracy in the oil region as former and new fighters resumed armed activities.

While the government was busy with the amnesty initiative in the Niger Delta, the jihadist terror group Boko Haram sprang up in Nigeria’s northeast around 2009. As the Islamic jihad insurgency festered, the group gained international notoriety for its kidnapping raids which is its means of generating funds for its terrorist operations.

Meanwhile, conflicts between herders and farmers in north and central Nigeria escalated during President Goodluck Jonathan’s tenure. This long-standing issue evolved into frequent incidents of kidnapping raids and cattle theft in rural areas. Now the conflict has spilled into urban areas, including Abuja, the nation’s seat of power.

Even in the southeastern part of Nigeria, once regarded as one of the country’s most peaceful regions, there are now instances of kidnapping allegedly carried out by Biafra secessionist fighters.

Victoria Eneze, a graduate at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, whose maternal uncle, James Taiwo, was kidnapped in Kogi state in North Central Nigeria in October 2023, believes that Nigeria’s kidnapping crisis tells of a failed intelligence system in the country.

Eneze said that while the family paid ransom after her uncle had spent 11 days in captivity, he was never released, and was never found. Eneze fears that her uncle may have died at the hands of his captors. She wonders why despite there being several phone calls between the victim and his family members, which the police were aware of, the abductors were untraceable. “Emotionally [and] financially, it has caused a lot of commotion. My mother has been crying. The last born of my uncle has been asking for his father. There is no security in this country,” Eneze told Inkstick.

Nigeria’s ex-Minister of Communications and Digital Economy, Isa Pantami, came under fire from Nigerians for mobilizing friends to contribute 50 million naira ($55,000), toward the ransom for the release of Nabeeha’s sisters. It was Pantami who in 2022, via the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), announced plans to fully bar phone lines from telecommunication providers if subscribers had not synchronized their Subscriber Identification Modules (SIMs) with National Identification Numbers (NINs). This measure aimed to enhance the government’s efforts to combat insecurity. However, despite these efforts, kidnappers persist in making untraceable phone calls to victims’ families without being caught, undermining the purpose of the initiative.

Defending himself, Pantami pointed the finger at security agencies, accusing them of failing to leverage his policy for tracking calls and other digital imprints of kidnappers. But for Timothy Avele, a security expert, and founder and CEO of Agent-X Security, based in Lagos, Nigeria, the telecommunication industry should take the higher share of the blame for allowing criminals to be untraceable. “The main culprit here are the telecommunications service providers who do allow unlinked SIMs to be active on their network. I personally investigated a case where a fraudster has over 70 lines without any NINs records on these active lines,” he said in an interview.

Nigeria’s Crumbling Intelligence System

Nigeria’s security sector woes have a long history. After seizing power from Major General Muhammadu Buhari through a coup in 1985, President Ibrahim Babangida in the following year split Nigeria’s security services into three distinct entities. The State Security Service (SSS), now rebranded as the Department of State Services (DSS) and nicknamed “Nigeria’s secret police,” was tasked with overseeing domestic intelligence. The National Intelligence Agency (NIA) was responsible for external intelligence and counterintelligence, while the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA) took charge of military-related intelligence both within and outside Nigeria.

Despite the continued existence of these agencies, experts argue that they have often focused on protecting those in power rather than ensuring the well-being of the average Nigerian. Nigerian security agencies have at different times made pledges to work and protect journalists, and to safeguard Nigerians. “We will continue to work together. At our part we are committed to any relationship that will deepen the sense of security and safety of media practitioners not just because we are police officers or we are constitutionally mandated to do so, but because we see the media as veritable partners,” the police said during a workshop with media practitioners in 2020.

Nonetheless, the security agencies have a problematic track record. During the “end SARS” protests in 2020, a social movement calling to end police brutality, Nigerian authorities cracked down on the protesters and killed at least a dozen protesters.

Critics also say that while security agencies successfully silence opposition, they have failed to act on warnings of impending attacks impacting civilians.

Emeka Okoro, lead security analyst with SBM Intelligence, believes that Nigeria’s intelligence gathering is not deficient but rather underutilized.

“Intelligence gathering in Nigeria is heavily focused on regime security rather than national security. This was seen during the Babangida regime. In order to make his regime coup-proof, Babangida decided to decentralize the power of the NSO (National Security Organization) into three agencies with a specialized focus. In present day Nigeria, focus on regime preservation has continued to remain, the order being the security of the government first, that of the political elite second and national security coming third. As a result, and given the lack of personnel, the threats they respond to are those they consider detrimental to the government of the day. The safety and protection of the average citizen is inconsequential,” Okoro said.

The police have claimed that a “shortage of tracking machines” is partly to blame for delays in addressing kidnapping cases.

The Cost of Negligence

To curb the rising incidents of kidnappings and terrorism, the Nigerian government has increased aerial warfare by acquiring drones from China and intensifying bombings from fighter jets. However, the lack of sufficient investment in intelligence has resulted in fatal casualties.

Last year in Nigeria’s Kaduna state, a military drone conducting aerial surveillance against terrorists mistakenly targeted and killed over 120 civilians, including children. In January 2017, the Nigerian Air Force mistakenly bombed a camp of internally displaced persons in a village, killing more than 100 displaced people and aid workers. The military, in an attempt to absolve itself, claimed it was due to a “lack of appropriate marking.” And on April 25, 2021, a Nigerian Air Force fighter jet targeting Boko Haram fighters mistakenly bombed a Nigerian Army truck leading to the deaths of over 20 officers.

The Way Forward

For Okoro, Nigerian security agencies must urgently retool their intelligence gathering architecture and enhance inter-agency coordination to avoid calamities. He says there is sparse collaboration between these agencies which is a hindrance to the fight against insecurity. “They still operate in isolation given the rivalry and mistrust that exists between them. Without meaningful collaboration between them, only a very limited success would be achievable. As a result of poor management, intelligence agencies have become reserved in the distribution of classified information to relevant authorities. One unfortunate realization about the problem with Nigeria is that almost everything is purposely designed to fail which gives the impression that lack of intelligence gathering is taking the fight against insecurity backwards,” he said.

For the Lagos-based Avele, “The security agencies must adopt a different approach to end or minimize to the barest minimum the scourge of kidnapping and banditry in Nigeria using affordable persistent ground monitoring technologies and of course sharing intelligence is a key factor in winning the battle.”

Avele believes that Nigeria should invest more in technology to aid successful operations, adding that “reskilling and upskilling of the personnel on modern techniques is vital.”

Amnesty International insists that Tinubu should regard the pervasive kidnapping incidents in the country as an emergency and implement measures to solve the problem. In a statement it warned that “failure to address the security concerns urgently will grossly enable human rights abuses.”