Olanrewaju Quadri was a techie way before it was cool. In 2016, after working as a trainee in a cyber café through his high school years, he started working as the shift lead in another cyber café to save for University. His new boss was a gig-based web developer who owned the café as a more stable means of income.

Quadri honed his tech skills quickly. Six months into the job, he was already working on large-scale web development projects. One time, he helped develop the entire website of a major Nigerian bank. When he got into University in 2018, he learned about gig platforms like Fiverr and Upwork. He created an account but he did not get the gigs. Instead, he worked for a friend who often got gigs and drop-serviced them to him. The money was great. When he worked for his boss, he was on a monthly salary of 20,000 naira ($25). With his new partner, he was making around 50,000 naira ($62) per project. Some months he would score as many as three projects, though sometimes, none at all.

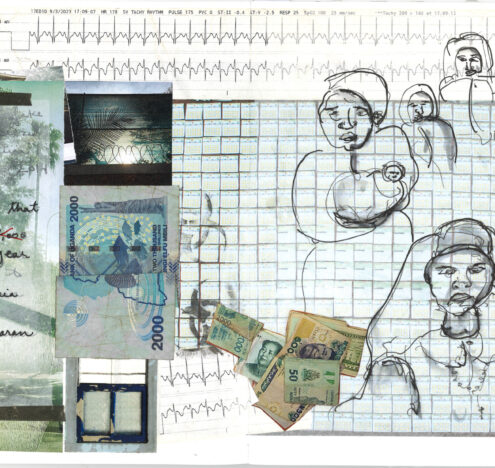

“It felt like gambling. That’s the only way you can make that sort of money in Nigeria,” Quadri said. The gigs weren’t consistent, but they didn’t need to be. In a year, Quadri bought a new laptop and moved into his own apartment. He started reaching out to a network of other developers. In retrospect, Quadri said he thought that would help it feel more real.

Quadri comes from a family of nine children. His dad had two wives. When he wanted to take up a cyber-café apprenticeship, his brother paid for it from his salary as a baker in Chicken Republic, one of Nigeria’s fast food chain restaurants. “The money was so surreal that my parents were concerned that I was doing cyber fraud,” Quadri said. At the end of 2019, he checked his bank statement and realized he’d made more than a million naira ($1,250) through that year. The same year, the Nigerian Government had just increased the minimum monthly wage from 15,000 naira to 30,000. When averaged, Quadri was making over two and a half times the new minimum wage.

In 2020, Quadri learned how to build “the perfect Fiverr profile” with help from a developer friend. The first gig came just as the pandemic was taking foot — he was hired to build a website for a thousand dollars — over 350,000 naira when converted to the local currency at the 2019 parallel market dollar to naira conversion rate. The pandemic stalled his education, so he poured all of his extra time and energy into work. “In July 2020, I made double what I’d made in the whole of 2019,” he said. “I started teaching others.”

The Boom

In October 2020, the African tech ecosystem grew rapidly. Paystack, a fintech built in Nigeria, was acquired by Stripe for $200 million. “When they acquired Paystack everything blew up,” says Olanrewaju Junaid, head of tech empowerment initiative Teach Africa. “Suddenly, everyone wanted to learn tech skills.”

Since 2020, driven by the pandemic and a global tech boom, the demand for tech skills in African countries has increased significantly, and so has the demand to hire those skills. Services to teach those skills, help those with such skills find jobs, and even help facilitate easy payment of their wages from across the globe have increased. Like Quadri, many young Africans perceive tech skills as a way out of the socioeconomic mire that surrounds them.

Although official data by Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics pegs unemployment at 4.1% using a controversial definition of unemployment that was introduced earlier this year, a report by leading global professional services firm KPMG estimates that Nigeria’s unemployment figure could top 40% this year. Currently, the minimum monthly wage is 30,000 naira, but the average cost of living is pegged at 319,787 naira per month, according to Numbeo. According to the World Bank, 30.9% of Nigerians live under the extreme poverty line in Nigeria.

A similar socioeconomic trend prevails across many countries in Africa. Ghana, another West African country, has been facing its worst economic crisis in a generation. South Africa’s unemployment rate was 32.9% for the first quarter of 2023.

In 2021, Nigerian talent-sourcing platform TalentQL launched AltSchool Africa to teach Africans tech skills. Earlier this year the platform graduated its first cohort of Software engineers, over a thousand students who’d spent a cumulative 2.7 million hours learning on the platform, according to co-founder Adewale Yusuf. Nitin Gajria, Managing Director of Google Sub-Saharan Africa, wrote that funding levels for African tech startups were at an all-time high.

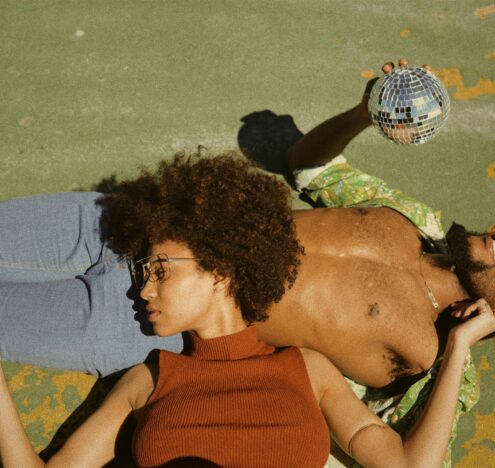

“Tech skills have disrupted the definition of jobs on the continent. Before the tech era, people would pray and bribe their way to white-collar jobs at banks and government ministries paying 100,000 naira, and then suddenly there’s [the] way of merit where you could earn triple of that [amount],” Junaid says. Most of these jobs also came with more freedom.

An important twist, Junaid says, is that tech skills were also a “Trojan Horse” for better working conditions. Remote workers working for multinational firms were held to a large extent to the labor laws of the Global North, which are more extensive and supportive than the very basic and rarely implemented laws of the Global South. International firms were looking to hire African talents, but the boom also increased tech-based firms in Africa, who were also out to hire talents.

To compete, local startups had to match pay levels and work cultures, Junaid says. “Tech startups were among the first workplaces with accountable work cultures and it was because of that influence from [the] outside tech industry,” Junaid says.

The Bust

“I think we saw it coming, but nobody expected it to be that bad,” says Junaid.

In 2023, a slowdown that began in the second half of 2022 led into a global economic downturn. At least five US banks have failed in 2023 alone, including the tech favorite Silicon Valley Bank. Stock prices plunged, investments decreased, and many businesses had to either close down or downsize.

“In the first nine months of 2023, African startups raised only $1.3 billion, compared to $3.3 billion and $2.9 billion during the same period in 2022 and 2021,” writes Sultan Quadri for Rest of World. Both African startups and international startups who’d hired Africans laid off talent at an alarming rate. “Businesses were resorting to slim, almost skeletal teams so many remote workers lost their jobs to people who were much closer to offices,” Junaid says.

At least 240,000 tech workers have been laid off work in 2023 alone, according to TechCrunch.

Adekunle Wahab, a student at the University of Ilorin who learned design in 2019 and landed a job as the lead designer of a Europe-based startup in 2021 was among those laid off. Quadri, who also was working in multiple contract roles as a developer for multiple firms also suffered. By March, Quadri says his monthly income which had peaked at over 2 million naira (around $2534) monthly dropped to around 400,000 naira ($506). He had it easy. Wahab was laid off from his remote work as a designer and had to go back to gig platforms, which had changed drastically from when he first started.

“There has been a slowdown in hiring and increase in layoffs across the industry as startups and tech companies try to navigate the economic downturn,” says Junaid. At least five African major startups failed in the first half of 2023 alone and others have had to slim down, pivot, and lay off workers.

“There’s still a lot of valid hope (about tech skills), but there’s been a reality check. Many people know that tech can also be a grueling, unpaying job.”

The dependence on international investment and the swift layoffs of African teams during restructuring efforts by companies highlight the structural imbalances that tech — however democratizing it claims to be — inherits from the worlds it is born into.

Junaid says African talents have been on an even more decapitating end of this downturn due to poor infrastructure, weaker social systems, and “being the most disposable arm of the system on both talent hiring and investment end.” Africa’s tech ecosystem is very dependent on funding from international investors, which predisposes it to downturns like this. “When there’s reduced investment, African investments are among the earliest cut off,” Junaid says. “Same thing with talents working in international companies. If there’s a cut, the African talents are likely to go first due to lesser economic interests in the country. Earlier this year, X (formerly Twitter) fired the entire Africa team in a bid to restructure and create a leaner workforce after being acquired by Elon Musk.

Today, Quadri says his income has increased but it takes more gigs to earn the same pay he made before. “I’m riding on the “African talent is cheap” narrative at the moment,” he says. Wahab, on the other hand, said he finally got a call back earlier this year, and he might be resuming as an in-house designer for another international startup next year. “I’m excited, but anything can happen at anytime,” he says.

Talents like Quadri and Wahab have been beneficiaries of a slight tear or malfunction in the fabric of global inequality. “Tech in Africa is a sort of economic democracy, but like its political equal it is very volatile,” says Junaid. The initial surge in demand for tech skills provided a glimmer of hope for individuals seeking economic empowerment in African regions grappling with high unemployment and widespread poverty. But the subsequent downturn exposed the precarious nature of their positions, with African talents often considered disposable in the global tech landscape. The dependence on international investment and the swift layoffs of African teams during restructuring efforts by companies highlight the structural imbalances that tech — however democratizing it claims to be — inherits from the worlds it is born into.