Khatib’s work, however, has taken on a renewed importance in recent months, as Israel carries out a military operation in the besieged Gaza Strip in response to the deadly cross-border attack Hamas launched on Oct. 7. On top of killing more than 22,000 people, Israel’s military campaign has destroyed scores of important cultural sites in Gaza, constituting what rights groups have called the “explicit targeting of Palestinian cultural heritage.”

Israeli air and artillery attacks have demolished historical and cultural buildings in Gaza, such as the Al-Omari Grand Mosque and the Gaza Municipal Library. According to the Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, international humanitarian law prohibits the deliberate targeting of cultural and religious sites in the absence of military necessity.

The preservation of antiquities in Gaza have taken a backseat to the needs of residents, whose daily lives amid Israeli bombing and a shrinking food supply have become a desperate fight for survival.

Meanwhile, the Palestinian diaspora and cultural centers outside of historic Palestine have stepped up to help preserve and document Palestinian culture and heritage. To many, the preservation of Palestinian culture is essential for the survival of the country’s identity, which they see as under siege.

For Khatib, Israel started by taking the land by force, and then moved onto either targeting or appropriating the cultural heritage. “They say the Palestinian dress is theirs, the keffiyeh is theirs, that falafel and hummus is theirs,” he said.

A Loss of Indigenous Knowledge

It is not just physical monuments and artifacts that are under threat, but intangible knowledge and customs that are passed on through generations. The wiping out of entire families from Gaza’s civil registries threatens to stop the reproduction of those customs.

Dr. Rami Zurayk, director of the Palestine Land Studies Center in Beirut, described how even before the current Gaza war, Israel’s occupation had fundamentally changed the nature of agricultural production and cultural practices around food in Gaza.

Traditionally, much of Gaza’s agriculture was geared around subsistence farming, with farmers growing typical Mediterranean staples such as cereals, olives, pomegranates and figs. Gaza’s coastal location also meant that fishing comprised a large part of the local food industry.

This has changed, however, since the advent of Israel’s occupation. Gazans’ ability to fish has been curtailed by Israeli restrictions on how far out fishermen can venture in their boats, and local development initiatives have encouraged farmers to start growing more profitable crops, such as cut-flowers and strawberries.

Changing farming practices under the occupation have created a “loss of Indigenous knowledge” and a pivot away from more traditional, sustainable farming,” Zurayk said.

This is extremely important to us, this anchorage of the Palestinians through the knowledge and the acknowledgment of their cultural heritage.

– Rami Zurayk

“You have an integrated system that’s based on the local ecology that completely disappears. It’s replaced by a non-integrated system based on the injection of funds,” Zurayk added. “Farming, food, the sharing of food — a lot of habits that create a society and anchor it disappear.”

The recent Israeli assault on Gaza has accelerated this loss in Indigenous farming practices. Not only have those who would teach or be taught these traditional farming practices been killed, but their farmlands have been damaged and, in some cases, razed.

Preservation and documentation of these traditional customs are key to ensuring that the concept of Palestine that survives the current war is one that Palestinians can recognize.

“This is extremely important to us, this anchorage of the Palestinians through the knowledge and the acknowledgment of their cultural heritage … So that Palestine does not just become a symbol, but continues to live on as an entity in the minds of the people,” Zurayk said.

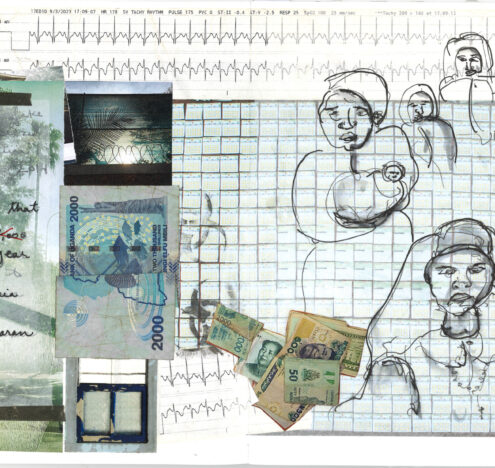

Palestinian Art as a Memorial, Resistance

Meanwhile, other cultural centers have taken it upon themselves to refocus attention on the Palestinian art they already collected and to use it as a means of nonviolent resistance amid the mass killing and threats to cultural heritage the Gaza war has wrought.

In Beirut, the Dalloul Art Foundation (DAF), one of the largest private collections of modern and contemporary Arab art in the Middle East, launched an exhibition entitled “The Little Prince of Gaza” on Dec. 20.

The exhibition pays tribute to the suffering of the Gazan children who are stuck in the embattled coastal enclave, juxtaposing it with the ethereal French children’s novel “The Little Prince,” in which a child travels the cosmos.

At the center of the exhibit is a cubist sculpture of a Gazan child made in 2010, now surrounded by almost a thousand ID cards with the names of children killed by Israel’s current military operation in Gaza.

“This was an installation that was executed as a memorial to the massacred children of Gaza. Today we intend to represent this structure, created in 2010 as the fragmentation of the lives of the children of Gaza, and the fragmentation of their limbs and body,” said Wafa Roz, the exhibition’s curator.