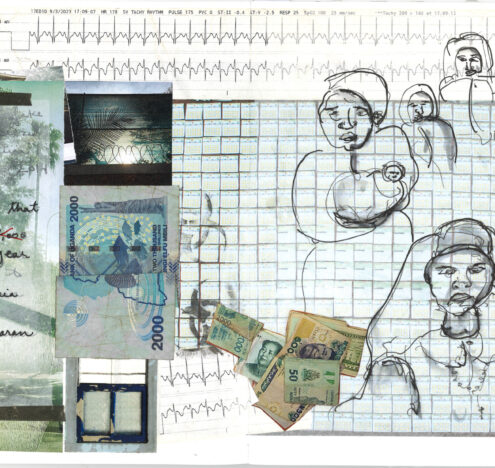

On July 26, Niger’s military junta announced the coup that deposed President Mohamed Bazoum.

Two days later, the disinformation had already started.

The earliest version of a video that X (formerly Twitter) users claimed was the Minister of Niger crying when summoned by the military to explain the country’s finances was posted on July 28. It fit perfectly into the social media frenzy around a coup that has been described as “one too many” by Abdel-Fatau Musah, the commissioner for peace and security at The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

By the end of July, the narrative had become a key supportive argument for the coup in Niger, especially among international commenters. Popular figures across the African continent like Ghanian businessmen Kofi Amoah and Nigerian youth political mobilizer Morris Monye took the video at face value and used it as the basis for arguments for and against the coup — mostly for.

Currently, there are at least 30 posts on X (formerly Twitter) peddling the same narrative, and the one with the leading engagements has racked up more than ten million views. Less than five of the thirty have the reader-added context that debunks the narrative.

The disinformation around the coup in Niger is noteworthy as a nexus of international geopolitics. Disinformation narratives have involved actors from across West Africa and the world, and viewers targeted are sometimes local Nigeriens, but often people around the region. That the country has had blackouts leading to a dearth of verifiably accurate information and has a complicated media industry with little to no editorial independence has only added to the storm of uncertainty.

Last week, Niger accused France of stockpiling weapons in ECOWAS states with plans of a military intervention. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger also signed a security pact solidifying their commitment to support Niger in the case of an ECOWAS invasion. The international community continues to debate how to manage the issue. And another coup soon followed in Gabon. While disinformation is false, it is clearly consequential. The tangible impact of the plethora of grainy, semi-fictional video collages is more clear than ever.

What’s the Point?

Disinformation is key to influencing public opinion, and in Niger, targeted disinformation campaigns have centered on three main geopolitical axes: the French, ECOWAS and Russia. Eliud Akwei, a senior data analyst at Code for Africa, which researches disinformation and influence campaigns across Africa, explained that the disinformation the organization has been tracking around Niger feeds into “anti-French narratives, anti-ECOWAS narratives, and then the third is a coordinated amplification of certain pro-Russian narratives.”

A major component of anti-French narratives has been the former colonizer’s relationship with Niger. For example, one rumor circulated that France got its uranium in Niger for €0.8/Kg as compared to €200/Kg in other countries. Currently, the global Uranium price — inclusive of Niger’s — is $56.25 per pound, slightly up from $56.15 before the coup. Another false social media narrative claimed that Niger banned Uranium exports to France and other EU countries — it didn’t. In August, after ECOWAS threatened military intervention if Niger did not reverse the coup, misinforming videos claiming that Nigerian soldiers had been arrested in Niger by Wagner and that a Nigerian “spy helicopter” was brought down circulated on TikTok. The videos played on the political tension between Nigeria, ECOWAS, and the military junta in Niger, and proved a sizeable source of fear to Nigerians who were already battling with rumors that youth corpers would be consigned to serve in the military.

“I’ve had to distance myself from everything because I don’t know what’s true and what’s not… Everything seems to be a lie or exaggerated.”

Taiwo Abdulfatai

Russia has also played a central role in driving disinformation narratives. In August, for example, a network of accounts that are used to drive engagement and encourage organic algorithmic propagation of content on social media — known as influence networks — on Facebook shared and amplified videos they claimed to be evidence of Russia delivering weapons in support of Niger’s military junta. When fact-checkers reverse-searched the videos, it showed that the videos were actually taken in different countries and at different times.

Akwei says there have been at least two influence campaigns about the arrival of Wagner troops in Niger, with one of these two originating from a Russian media outlet. Akwei also says that Wagner’s disinformation network has been active in the post-coup Niger disinformation atmosphere, despite its own challenges. “Prigozhin, the then Wagner leader basically said after the coup that the coup is a much-needed step towards independence, and this has been amplified by various pro-Wagner accounts on social media,” says Akwei. “It also said in the same stretch that Wagner was available to support the military junta in Niger.”

Who is the Audience?

Many of the accounts running these campaigns have been from places outside Niger. “A transnational network of Facebook accounts is a major driver of the disinformation and coordinated campaigns that we’ve identified,” Akwei says. “These accounts are mainly administered from francophone West African countries such as Burkina Faso and Mali, and a handful of them are also run from Western Europe — mainly France and Belgium. Only a few of the accounts are actually being run from Niger.”

Akwei says he and his fellow researchers discovered that many of the accounts sharing fake news around the Niger coup have been involved in similar campaigns across West Africa, such as around the coup in Burkina Faso last year.

Internet-driven disinformation is not a straight sell in Niger — only 22% of the country’s population uses the internet, according to the World Bank. As an extension, many of these narratives and influence campaigns have also targeted people from outside Niger, especially Africans who experience the same sociopolitical themes as Nigeriens.

Taiwo Abdulfatai, a 25-year-old Nigerian, says he took many of the narratives at face value. For some time, it made him a supporter of the coup. After he found out many of the narratives were false, it “numbed” him. “I’ve had to distance myself from everything because I don’t know what’s true and what’s not,” Abdulfatai says. “Everything seems to be a lie or exaggerated.”

As also noted by Akwei, many of the fact checks and debunks of this disinformation only had a fraction of reach as the original narrative.

In moments of political turmoil like this, access to unmanipulated information is crucial to all stakeholders. In the short term, disinformation cripples decision-making, and in the long term, it can perpetuate poor governance and create a legacy of false information, Akwei says. “So once the events play out, and things settled down, a question to ask yourself is what happens to the structures built to carry out these campaigns and the people who have been equipped with the skills, they inevitably turn to other opportunities,” says Akwei. “These assets are then used to drive hate speech, ethnic bigotry, political influence, and elections interference, and then it creates like a vicious cycle.”

What to do?

While efforts by fact-checkers have been put in high gear, properly moderating disinformation on social media networks is still a major challenge. Akwei thinks that tech companies have the responsibility to take down accounts at the center of these campaigns. Policymakers also have the responsibility to implement measures to ensure that sanctions are placed on identified sponsors, and financial streams used to sponsor campaigns are blocked.