The day is Wednesday, May 17, 2023, and DSM Capella, the last Ship carrying about 30,000 tons of corn has just departed the port of Chornomorsk in Ukraine. As it sails towards the shores of Turkey, tension hangs in the air — will it really be the last one? If so, what will this mean for global food security?

Several days before the ship sailed through the corridor of the Black Sea, Russia had vowed that there would be no extension to the Black Sea Grain Initiative — a key export deal that was set to expire on May 18 — unless world leaders approved a list of demands that would soften the restrictions and sanctions hindering Russia’s agricultural export activities. The United Nations and other relevant stakeholders met repeatedly to work toward the renewal, but the discussions were complex.

Then finally, while the clock was ticking, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a key facilitator of the export initiative, announced to the media in a televised broadcast that Russia had agreed to a two-month extension of the deal.

Since Aug. 1, 2022, over 30 million tons of food and agricultural products have left the Black Sea region under the deal. A collapse in the negotiations would have sparked fears of a return to the dire food insecurity of the second quarter of 2022 when the blockade on Ukraine’s ports led to a global food shortage. While the global food system — and so the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which demonstrates this intricate web —- affects everyone, the Horn of Africa, which has already been hard hit with climate emergencies and armed conflicts, is particularly vulnerable.

While the renewal is a relief, its short duration means the situation remains tenuous. Some African thought leaders emphasize that the continent’s vulnerability points to a need to invest in sovereign food stability and reduce the dependence on imports.

The Link Between Ukraine And Africa

In Feb. 2022, when Vladimir Putin launched a Special Operation in Ukraine, aside from the heartbreaking scenes of the catastrophic fall of Ukrainian infrastructure, and the growing numbers of internally displaced persons, three key seaports in Ukraine — through which millions of tons of grains are usually shipped to Europe, America, Asia, and Africa — were captured or blockaded by Russian Forces. It led to a global food shortage.

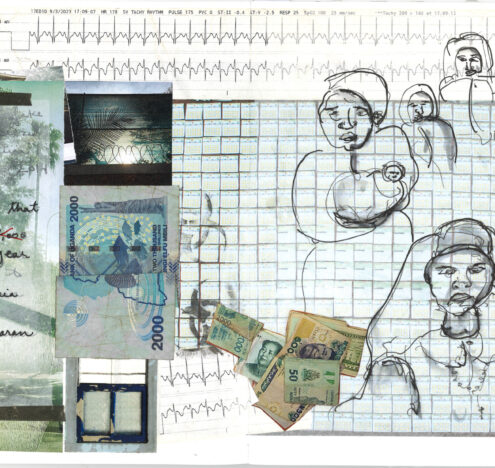

Between 2018 and 2020 Africa imported $3.7 billion worth of wheat from Russia — nearly a third of its global wheat import — and another $1.4 billion from Ukraine.

Prior to the war, Russia and Ukraine were among the top producers and exporters of grains and fertilizer in the world. Due to severe climate damage, poor governance, and the spillovers of the COVID-19 pandemic, the African continent is heavily dependent on imports of grain and fertilizer and so had an intricate interweave with that region. Between 2018 and 2020 Africa imported $3.7 billion worth of wheat from Russia — nearly a third of its global wheat import — and another $1.4 billion from Ukraine. Eritrea, for example, imported 100% of its grain from either Russia or Ukraine while Somalia imported about 90% of its wheat from the same region.

When the ports were blockaded, the impact was drastic. In Sudan, where the majority of its populace feed on wheat products, the price of wheat rose by 92% and worsened starvation, inflation, and the food crisis.

“Across Africa, there are cities where wheat products have become a part of the staple diet of people on low incomes: packs of sliced bread, pasta, noodles, biscuits, and so on. Wheat products are often the most convenient for working mothers who come home from work and have to offer their hungry kids food in a hurry. For them, any increase in the prices of such products is a hardship.” Steve Wiggins, The Overseas Development Institute’s food security specialist, based in the UK, told Inkstick.

Statistics show that in the struggling economies of sub-Saharan Africa, food consumption and expenses account for about 40% of household spending, compared to 17% spent of household spending in wealthier economies. So a sudden increase in food prices has an outsized impact on families’ overall economic stability and spikes in food prices can push people deeper into poverty.

“Any news of grain flowing from the Black Sea, with cereals exports from Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine, is good news for it will really help push down the prices of grains that have been high over the last three years, above all those of wheat, maize, sunflower,” Wiggins said.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative

In July 2022, a joint effort of The UN, Turkey, Russia, and Ukraine to alleviate the global food crisis was rewarded when a formal agreement in Istanbul was reached that would allow safe transportation of Russian and Ukrainian agricultural products through the Black Sea corridors to other nations across the globe. The deal included permitted inspections by a team of officials of the United Nations, Turkey, Russia, and Ukraine. In the early days of the deal, approximately 25% of the cargo ships traveled to low and lower-income countries where populations face food crises, including the eastern part of Africa.

“The deal in itself ensures food price stability in the global market. It thus results in ensuring that the food prices in countries such as Somalia, Kenya, Sudan don’t see a massive increase in food prices. This helps the population with food being available and affordable.” Shashwat Saraf, Regional Emergency Director, International Rescue Committee, East Africa, said to Inkstick.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan affirmed in a live interview with Turkish media last November during the negotiations for the second term of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, that Africa’s food shortage was critical and that it was in need of more grain to lessen the food crisis. “The situation in Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan is not good at all. If there is a problem in any other less developed countries, we will carry out shipments to these countries,” Erdogan said to the Turkish media.

Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s veteran foreign minister told reporters in a press conference, however, in April that the Western sanctions on Moscow have limited Russia’s progress and inclusion in the export deal and he expressed Moscow’s loss of confidence in the realities, goals and the mission of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, insisting it was no longer a humanitarian initiative, but a “commercial enterprise” that caters to the Western interest and scheme.

“I do think that the deal is in between the big political game being played by different parties/sides. We really need to see it primarily from a global food security lens and do what is best for humanity across the world. We have all agreed that food and humanitarian assistance cannot and should not be used as a weapon of war and there is a need to reinforce and reiterate it with all sides to the conflict,” said Saraf.

Beyond Foreign Aid

As African states continue to depend on decisions made by foreign leaders, analysts say it is time Africa took more steps in actualizing its dream of self-sufficiency in the agricultural sector.

“I think the solution to Africa’s over-dependency on imports for consumption in Africa would be to focus on maximizing the productivity of its arable lands,” Peter Nwagbogu, Market Intelligence Coordinator for Export Market Development at the Africa Continental Free Trade Area Agreement – Nigeria Working Group, told Inkstick. “Africa must really look inwards, there are several natural provisions but there is need for specific and realistic regulations and policies that will actualize these agricultural potentials in Africa.” Ikemesit Effiong, the Head of Research at SBM Intelligence, an Africa-focused risk consultancy, spoke to Inkstick.

In the last few years, Africa has seen a flurry of international visits — and more promises by World leaders to several African host leaders have been made. But some experts see it as a rebirth of the 19th century Scramble For Africa and argue that African leaders must determine their future without depending on the promises of the visiting world leaders. “I have looked critically into the situation and I can emphatically say that most of the [grain] price rises materialized before the invasion in late Feb. 2022,” said Wiggins.

“I think the key factors affecting [grain] prices [in Africa]) are domestic: harvests, conflict, inflation. World prices of commodities play only a minor role,” Wiggins said. “As ever, much of Africa’s destiny is in African hands. Does not mean that external circumstances do not matter, they do: but just to stress that Africa can live to a greater extent without the outside world. Thank goodness!”