Celebrated humanitarians, a Netflix film and potential jail time for those who volunteered with some of society’s most vulnerable form the background of a complex case taking place in Greece, one of Europe’s southeastern most countries and a first point of entry for many refugees and migrants reaching the continent.

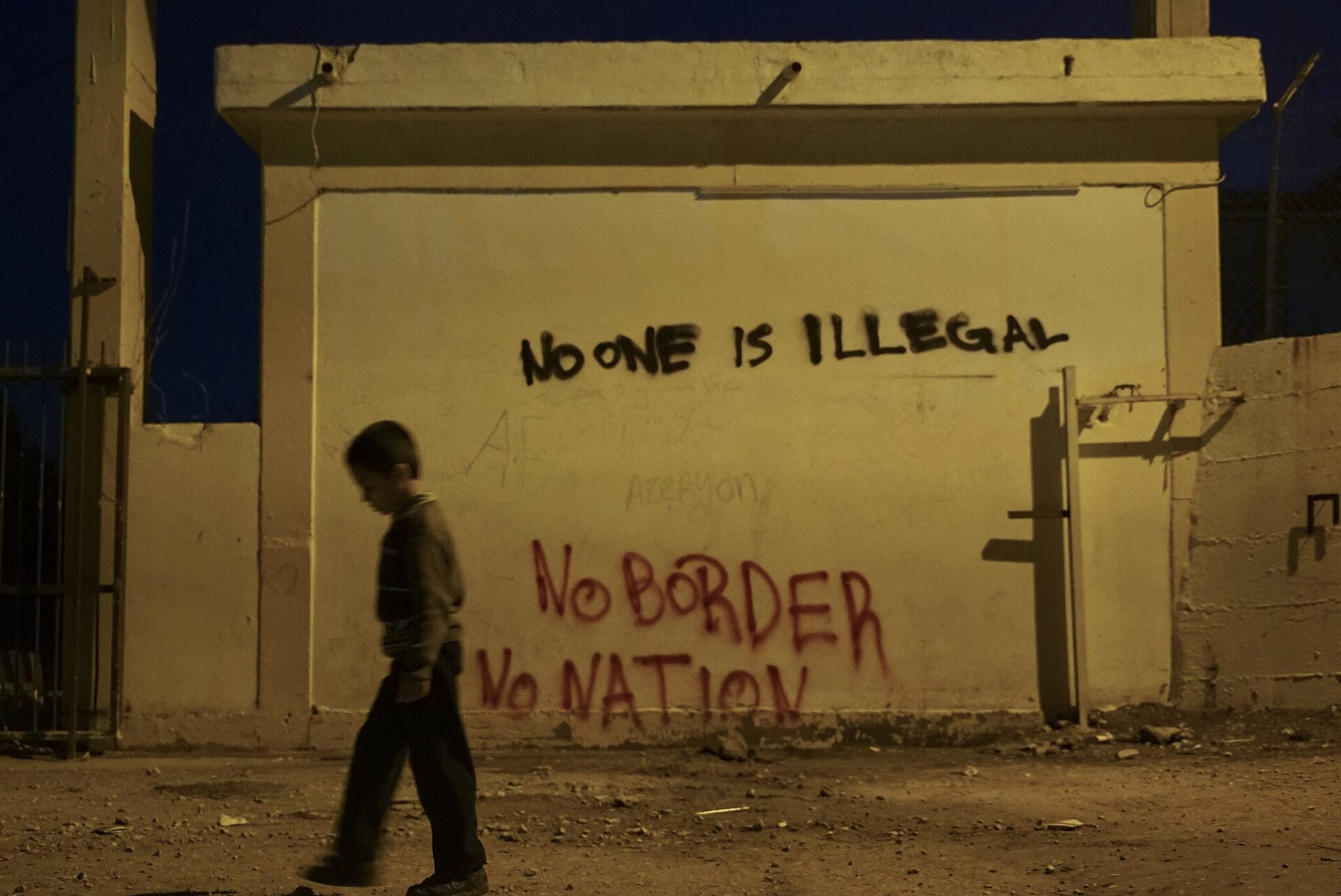

As rain falls on a gray January day on the island of Lesbos, a group of people stand outside a courthouse holding up placards painted with large black capitals that read “Free Humanitarians” and “If Helping Is a Crime, We Are All Criminals.”

Lesbos, one of the Greek islands closest to Turkey, was once the epicenter of refugee arrivals during the “refugee crisis” between 2015 and 2016, when more than a million people arrived on Greek shores seeking sanctuary. It attracted scores of volunteers and NGO workers doing everything from translation to handing out warm clothes, blankets, and food to new arrivals.

Several former volunteers and NGO employees are on trial for misdemeanor charges including espionage related to their time working with refugees on the island. The prosecution has alleged the accused used an encrypted messaging service to communicate — which the defendants say is nothing more than the popular application WhatsApp.

The case has attracted international attention and condemnation of rights groups including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International who have said the charges are trumped up and called for them to be dropped with Amnesty terming them “unfair and baseless,” and part of a wider crackdown on civil society in Greece.

Critics also say the case is emblematic of a disturbing trend across the European Union: authorities clamping down on humanitarians who help refugees and migrants, even as the number of forcibly displaced people across the globe continues to swell each year, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

In Lesbos, the proceedings have dragged on for years with several of the accused, including two young volunteers, put in harrowing pretrial detention for over 100 days after arrest in 2018. Last year, several defendants had the charges dropped due to procedural errors by the prosecution. A fresh trial began in January 2024 after the prosecution appealed for misdemeanor charges to be reinstated against the Greek-speaking defendants and those who had not turned up to previous court dates.

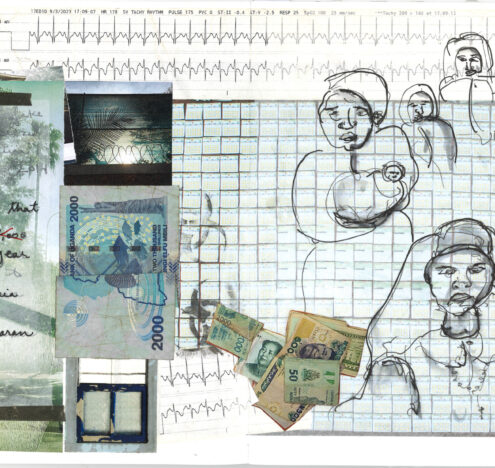

A larger group face more significant felony charges, including human trafficking, which their lawyers have called unfounded. Among those contending with further prosecution is Sara Mardini, a Syrian refugee who was celebrated along with her sister, when they dragged their sinking refugee dinghy to the shores of Lesbos, likely saving all those onboard — a story which was later turned into a Netflix film “The Swimmers.”

Drop in the Ocean

The Lesbos trial is a drop in the ocean of criminalization across Europe, according to research published by the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants, which noted that in 2022 there were “at least 102 human rights defenders facing criminal or administrative proceedings in the EU for acts of solidarity with migrants,” and warned the numbers could likely be larger.

Silvia Carta, Advocacy Officer for Migration Policy at PICUM told Inkstick that the numbers showed that there was a “problem” and that they were noticing a growing trend of criminalization across Europe, listing countries such as Italy, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland as a focus.

Carta said that they had seen that many people ended up being acquitted or given very low charges but ended up in legal limbo for “extremely long periods of time.” Carta pointed out that criminalization is targeted not just towards NGO workers but also migrants themselves, many of whom have already been jailed after accusations of smuggling when found at the helm of the refugee boat.

Seán Binder, a 29-year-old German citizen and former lifeguard, had the misdemeanor charges against him on Lesbos dropped last year but similarly still faces felony charges that could lead to up to 20 years in jail. He told Inkstick that the act of criminalizing humanitarian work “scares” people away even if the charges rarely, if ever, result in convictions.

“I’ve spoken to so many people who are afraid to engage in search and rescue or even do any kind of solidarity work,” he said, “and that’s for several reasons, including that there’s been a hardening of attitudes towards migration in general … but principally because people are afraid, and they’re scared. Organizations are doing less work because they don’t know what they’re allowed to do or rather they don’t know what things will attract negative attention from the police.”

In Italy, a country which, like Greece, has seen significant refugee arrivals, migration has become a hot-button issue particularly with right-wing and far-right politicians laying the blame on NGOs doing search and rescue activities and accusing them of “smuggling.” In turn NGOs have called for an end to political harassment of their work and the obstruction of humanitarian assistance at sea, claiming their endeavors are being complicated by restrictive policies and toxic political narratives.

Organizations are doing less work because they don’t know what they’re allowed to do or rather they don’t know what things will attract negative attention from the police.

– Seán Binder

The crew of the search-and-rescue boat Iuventa felt the full force of Italy’s hostile turn towards migration when their vessel was seized by authorities in 2017 and the crew put under investigation for “aiding and abetting unauthorized immigration,” which they strongly deny. Sascha Girke, the former Head of Mission aboard the Iuventa told Inkstick that the case, and others like it, generated significant attention for right-wing politicians and press.

“Chilling Effect”

“I think from a political perspective it’s a good vehicle for right-wing media and politicians to pick up single people and say they are criminals,” Girke said. “It’s good to have headlines saying that ‘we are going against the criminals,’” noting that there appeared to be a similar approach in both Italy and Greece.

In Poland, volunteers dropping food and aid to asylum seekers who have crossed from the Belarusian border have also faced harassment and criminal charges of aiding illegal border crossings. One 20-year-old Polish volunteer, Weronika Klemba, who was accused in March 2022 of human trafficking, finally had the charges against her dropped in Dec. 2022 — but not after being initially detained for 48 hours and having her family home searched. “My offense is that I did not want to let people die who are not welcome by Polish authorities,” she later said of the ordeal, as reported by the newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza.

In a press release published last year, Human Rights Watch’s Bill Van Esveld warned that the Lesbos case had a larger, more concerning context for humanitarian work in Europe noting it “has not only had a chilling effect on saving lives, it has turned laws and facts on their heads and placed the liberty of humanitarians from across the European Union at stake.”

As Europe turns towards what campaigners have said is a more “fortress”-like approach to its borders, people across the continent face prosecution for actions as simple as giving food and hot tea to migrants in need.

The way Girke sees it, even the simplest acts of solidarity are perceived as a threat by countries across the continent and have driven them to ramp up efforts to crack down on providing aid to refugees and migrants. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a rescue team at sea, or someone who is taking people to their home, giving them shelter or food or medical support, or maybe just a lift to the next train station,” Girke added. “All these little or bigger efforts are disturbing the border machinery, and that’s why they want to close it.”