On Feb. 1, the day the Greek Orthodox Church honors Saint Tryphon, known among farmers as the protector of fields, 60-year-old Fotis Papadopoulos made his way to church to pray for a “good harvest” this year. As a farmer and president of an agricultural collective in Larissa, he says, he knows the hardships that have hit Greek farmers.

Papadopoulos says he and others like him face growing expenses, crop losses caused by devastating wildfires and floods last year, and imports from Ukraine and Latin America entering the market at “humiliating prices,” leaving farmers in Greece and around the European Union struggling to get by.

The rising price of electricity, he explained, stands out as a “huge problem” for Greek farmers. “The electricity you consume at your home cannot be the same [price] as the electricity you consume in the primary sector,” he added. “Just like oil. You can’t have the same price for oil for your car and the same for your farm vehicle.”

The spike in operating costs has hit farmers doubly hard, in part, because the prices for which farmers can sell their products — corn, cotton, durum wheat, and barley, for instance — are nearly half what they were in 2022, Papadopoulos said.

Despite the lower prices companies purchase products at, the price tags on supermarket shelves are largely consistent with 2022, he added. The Greek government, he argued, is “turning a blind eye to the companies” making higher profits in a time of inflation.

Such hardships have sparked protests across the EU. In January, French farmers began to block roads to protest rising costs, taxes, regulations, and the same competition abroad that Papadopoulos and others view as unfair. Similar demonstrations broke out across the bloc — from Spain to Italy, from Lithuania to Belgium.

In key countries, such as France, Belgium, and Germany, protesting farmers have pointed the finger at the EU’s relaxation of importing restrictions for war-ravaged Ukraine and powerful agricultural producers elsewhere. They have also sounded the alarm on swelling production costs and rising rates for agricultural electricity, as well as subsidies being repealed or reduced.

“Many Challenges”

Last week, farmers took their fight to the seat of the EU’s power. Many gathered in Brussels, hurling stones and eggs at the European Parliament and shooting off fireworks. In response to the continent-wide unrest, the European Commission, the EU’s executive branch, proposed limits on agricultural imports from Ukraine and fewer restrictions on land use for European farmers.

Despite the “many challenges,” Commission chief Ursula Von der Leyen has promised change. “I’m very sensitive to the message that farmers are concerned by administrative burdens,” she said, later adding: “Farmers can count on European support.”

Olof Gill, a European Commission trade and agricultural spokesperson, echoed Von der Leyen’s comments, insisting that the institution “is listening closely to the concerns expressed by farmers in protests currently taking place in several [EU] member states.”

Gill insisted that the Commission is “aware of issues and concerns at the earliest stage, and we maintain a dynamic two-way dialogue with these organizations to inform our work.”

In a Jan. 31 statement, the Commission announced a proposal to renew the suspension of import duties and quotas for Ukrainian agricultural producers, as well as to extend an annual suspension of import duties for Moldovan agricultural products.

The proposal also includes an “emergency brake” on poultry, eggs, and flour — “the most sensitive products” — that would allow for tariffs to be put back in place to prevent those imports from surpassing the average levels of 2022 and 2023.

“Ridiculous”

Greece is home to hundreds of thousands of farmers, and the agricultural sector employs some 400,000 people, around 10% of the workforce. Nearly a third of the country’s population lives in rural areas, a share that is higher than the EU average.

In Orestiada, situated in the country’s northeastern Evros region, many farmers have joined the ongoing protests. According to Elias Angelakoudis, a 41-year-old farmer and president of the Orestiada Agricultural Association, Greek farmers face certain unique challenges.

They want to call it a more ecological agricultural policy, but what they want to pass has nothing to do with the environment.

– Elias Angelakoudis

While many other countries had a discounted rate for agricultural oil, that was not the case in Greece, where the government issued a decree that priced diesel on per crop basis. “The amount we were getting was ridiculous [and] too small,” he said.

On Feb. 3, farmers from several regions, including Orestiada, rallied outside an annual agricultural trade fair in Thessaloniki, the country’s second largest city. They marched and dumped apples and chestnuts in the street outside the meeting, local media reported. Some have also called on protesters to ramp up their pushback and block highways.

A day earlier, the Greek government, headed by the conservative New Democracy party, unrolled a support plan for farmers: tax subsidies, discounted electricity for a five-month period, and expedited recovery compensation for those who lost income thanks to floods that hit central Greece last year.

When it comes to the farmers’ criticisms, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has defended his government’s record. “Since 2019, we have reduced taxation and insurance rates, provided incentives for further reduction of taxation in cooperatives, and activated the measure of reimbursing the special consumer fuel tax for 2022 and 2023,” he recently said on social media.

“Completely Rigged”

Farmers rallying across Europe have placed a revision of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which implements agricultural subsidies and other programs, high on their list of demands.

Olof Gill, the European Commission spokesperson, insisted that “the Commission’s support for the agricultural sector is a constant of the European Union,” explaining that more than 300 billion euros will be distributed to farmers in the bloc between 2023 and 2027 as part of “CAP Strategic Plans.”

But Angelakoudis said CAP is “anachronistic” and fails to adequately compensate those who have experienced heavy crop damage. “It does not currently subsidize production,” he added. “They want to call it a more ecological agricultural policy, but what they want to pass has nothing to do with the environment.”

Take, for instance, so-called “eco-schemes” that make up part of the CAP plan to achieve a European New Green Deal, Angelakoudis said. A quarter of the budget is earmarked for eco-schemes, including direct payments, incentives for farming practices that are friendlier to the climate and the environment and “animal welfare improvements.”

“We are supposed to improve the ecology of our fields through our own actions via the ecological schemes, and we will get paid for it,” he added. “This is not the case. So far, the ecological schemes are not progressing. The ones that are progressing are completely rigged so that certain companies will make a profit … because in the end, we are paying for the ecological schemes so that we can make some money. So far, we have not received a single euro.”

“They Drowned Us”

When Storm Daniel hit parts of the Mediterranean in September 2023, at least 17 people died in Greece. Some climbed onto the rooftops of their homes to save themselves from the widespread flooding. Helicopters and rubber boats were deployed to rescue people stranded by the storm. The flooding toppled homes, destroyed roads, and collapsed bridges.

In flood-devastated communities including Karditsa, Larissa, and Volos — areas in the Thessaly region responsible for an estimated 10-12% of the country’s gross domestic product — large swaths of agricultural land were also destroyed.

Farmers from these areas have played a key role in leading the wave of protests in Greece. Sotiris Antoniou, a 34-year-old cotton, corn, and clove farmer and president of a farmers association in Palamas, a town in Kardista regional unit, said cleaning the damaged fields can cost anywhere up to 9,000 or 10,000 euros ($9,677-$10,752). “This amount cannot be afforded by a farmer,” said Antoniou. “And in the end, they drowned us.”

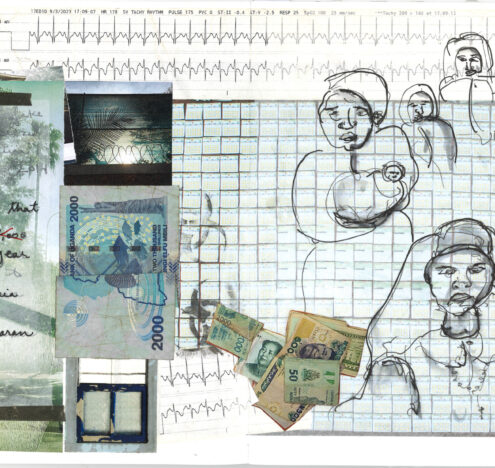

Antoniou said that farmers are ready to return to work, but they cannot do so without proper assistance. Some farmers were given 2,000 euros ($2,150) to help with destroyed machinery, he added, “but even [for] those who received this money, what can anyone fix with 2,000 euros? This money is not even enough for the oil for the machines.”

Meanwhile, as the farmers are left waiting for help, much of the Thessalian plain — which has around 15% of the country’s agricultural land and is known as “Greece’s breadbasket” — remains uncultivated, bogged down with mud and debris, and inaccessible, he explained.

Back in Larissa, Fotis Papadopoulos insisted that the farming community’s problems are not a secret — the Greek government knows “it is impossible for the farmers to cover the costs” of making up their losses and producing the agricultural products the country needs. He asked, “Is there a person on the planet who can work without earning anything?”