As you might imagine, those of us in the nuclear field are anxiously awaiting the release of “Oppenheimer,” not just to see Cillian Murphy (though that’s a big draw for me, personally), but also to see how much the film got right and wrong about this major piece of nuclear history. While I’m sure many stand ready to correct — or praise the accuracy of — scientific and technical aspects of the film, I’ll be evaluating two key themes: Does the film address impacted communities, and how does it represent J. Robert Oppenheimer?

The stories of people affected by the Manhattan Project have long gone ignored, unaddressed, and underrepresented in discussions of nuclear issues. It might be naive of me to hope for better from a major Hollywood film, but with a price tag of $100 million, it’s fair to expect Christopher Nolan to produce a film that tells the full story. Now, we won’t know exactly what will be depicted until next week, but, if 2017’s “Dunkirk” is any indication, some of the most impacted communities will be noticeably absent from the narrative. If Nolan wants to paint the fullest cinematic picture, he should include nods to the uranium miners in the Navajo Nation and Belgian Congo (and the victims of a Cold War proxy ground in Congo thereafter) and the downwinders of nuclear testing.

The Unmentioned Miners

The Manhattan Project would not have been possible without uranium, a natural element used in nuclear bombs that must be procured from mines. Three locations supplied the Manhattan Project: the Eldorado mine in Canada, the Shinkolobwe mine in Belgian Congo, and mines in the Colorado Plateau. The procurement of uranium from these mines was a dangerous process for miners, leading to disastrous health effects and, in the case of Congo, a political assassination and brutal civil war.

Approximately 14% of the uranium used by the Manhattan Project came from Navajo uranium miners in the Colorado Plateau. According to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), Navajo miners extracted nearly 4 million tons of uranium ore from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s. The Navajo miners worked for minimum wage or less, being exposed to the harmful effects of radiation without their knowledge. Per FAS, they became “the most severely exposed group of workers to ionizing radiation in the US nuclear weapons complex,” with high rates of lung cancer recorded, while the US government made the conscious decision to keep them in the dark about the health effects.

Scientists attempted to bring to light the effects of radiation exposure on miners as early as 1942, but in some cases, were barred from releasing further publications on the subject. In 1994, the Department of Energy released a previously secret document written in the late 1940s that made clear the government’s knowledge of radiation effects and the key reasoning for keeping the information from miners (surprise: it was because of money). The report states:

“We can see the possibility of a shattering effect on the morale of the employees if they become aware that there was substantial reason to question the standards of safety under which they are working. In the hands of labor unions the results of this study would add substance to demands for extra-hazardous pay… knowledge of the results of this study might increase the number of claims of occupational injury due to radiation.”

If Nolan wants to paint the fullest cinematic picture, he should include nods to the uranium miners in the Navajo Nation and Belgian Congo (and the victims of a Cold War proxy ground in Congo thereafter) and the downwinders of nuclear testing.

In August 1939, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, alerting him to the possibility of an atom bomb. In his letter, Einstein explained the necessity of uranium, pointing Roosevelt in the direction of Congo (yeah… despite his change of heart about the use of nuclear weapons, Einstein wasn’t the “good guy” during this time, either). He wrote, “The United States has only very poor ores of uranium in moderate quantities. There is some good ore in Canada and the former Czechoslovakia, while the most important source of uranium is the Belgian Congo.”

While mines in the Colorado Plateau and the Eldorado mine in Canada provided a large portion of uranium for the Manhattan Project, the project would not have been possible without the Shinkolobwe mine in Belgian Congo. The ore found in the Shinkolobwe mine contained the richest deposits of uranium in the world, with concentrations up to 7,000 times higher than uranium ore mined in the United States. The mine ultimately provided two-thirds of the Manhattan Project’s uranium and would sentence Congo to a role as a Cold War proxy ground after World War II.

Congolese miners worked for Belgian bosses (who, not the miners, reaped the profits of this rich mine) and American customers, under the same dangerous conditions as the Navajo miners and were left in the dark about the health effects they were being exposed to and the end product of their labor. Miners and their families have reported serious health issues likely related to radiation exposure, and none knew of their contribution to the Manhattan Project.

US officials, Manhattan Project Director Lieutenant General Leslie Groves in particular, were terrified of Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union discovering the incredible resource that was Shinkolobwe, and efforts were made even after World War II to prevent Soviet discovery. A US spy network was established in Congo, and after the United States dropped its nuclear bombs on Japan, credit was given to the uranium mine in Canada, not Shinkolobwe.

On June 30, 1960, Congo gained independence from Belgium with the election of its first democratic leader: Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. During the Manhattan Project, US officials negotiated with Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the Belgian company that owned the mine in order to ensure nearly all of the uranium from Shinkolobwe was sent to the United States and the United Kingdom. Once elected, Lumumba made it clear that he would not allow the United States the same control over Congo’s uranium as Belgium had.

When Katanga, the province that contained Shinkolobwe, seceded from Congo on July 11, 1960, Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for assistance after being turned down by the United States. Worried by this development, the CIA, under authorization by Eisenhower, led a mission to assassinate Lumumba on Jan. 17, 1961. Congo was subsequently plunged into a violent civil war for four years, concluding with the installation (aided by the CIA, of course) of Joseph Mobutu as leader of Congo. Mobutu ruled as a dictator until 1997.

In the Path of Fallout

On July 16, 1945, the United States conducted the first-ever nuclear test explosion, known as the Trinity Test, in Alamogordo, New Mexico, of which viewers of “Oppenheimer” will see a non-CGI recreation (umm… what do you mean, Nolan?). Officials of the Manhattan Project told the public that the explosion was caused by detonation of ammunition and other pyrotechnics. In order to maintain secrecy, residents of New Mexico and surrounding areas were not warned about the Trinity Test nor evacuated prior or told about the health hazards posed to them by the fallout.

When the radiation safety chief of the Manhattan Project was alerted in 1947 to a concerning rate of infant mortality downwind of the test, his assistant assured the concerned healthcare provider that “the safety and health of the people at large is not in any way endangered.” However, according to data from the New Mexico Health Department, the infant death rate was 38% higher in 1945 than in 1946 and 57% higher than in 1947.

Those who lived in the fallout path of the Trinity Test became known as “downwinders,” along with people who lived downwind of the 100 atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site from 1951 to 1992. Many members of this group have reported diseases such as heart disease, leukemia, and other cancers, of which they had no prior family history. They have fought for more than 70 years for recognition and compensation from the US government for radiation exposure.

Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) in 1990, a statute that provides a one-time payment to those who have been diagnosed with health issues like cancer due to radiation exposure from nuclear tests or uranium mining. However, victims of radiation exposure have raised valid critiques of the legislation, noting that it only applies to a small set of impacted areas, leaving many downwinders ineligible for compensation. Furthermore, the standard of proof for the few that qualify under RECA is unnecessarily burdensome, especially given inadequate data collection following the Trinity Test, leaving many victims uncompensated.

It’s Not Just About Oppenheimer

These impacted communities deserve to have their stories told alongside that of the man who made the bomb.

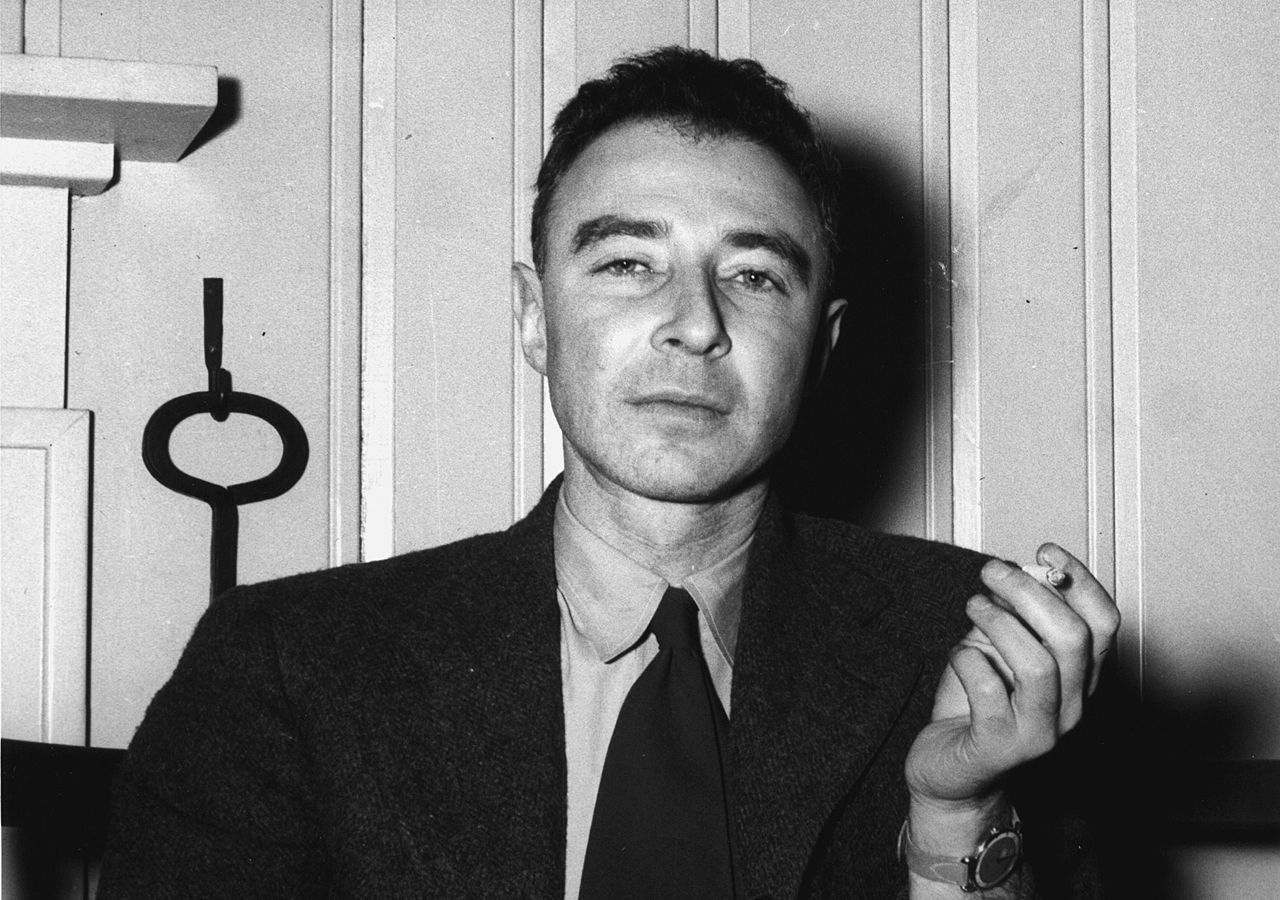

Another final, crucial element I’ll be watching — and you should, too — is how Oppenheimer himself is portrayed. Pay attention to how the film wants you to feel about him. Is he put to us as a genius, a leader, a man of great importance? More likely, are we meant to witness the internal conflict he faced after creating nuclear weapons and walk out of the theater thinking of him as a morally gray, complicated man? Are we meant to forgive him?

Hopefully, with this information and preparation, you’ll be able to watch “Oppenheimer” with a sharper eye, waiting to see if Nolan tells the full story.