“The banana smells so good, can you please buy me one, I want to taste it,” I asked my father at the market when I was in the third grade in the 1990s, and when Iraq was under economic sanctions. “Oh, my dear, those are fake, look, it even has stickers on them,” my Baba responded. His response brought on my dilemma. I know my Baba doesn’t lie, but those bananas smelled too real to be fake. I only wonder how hard it must have been for my father not to be able to buy me that banana.

My family had to be creative to survive in Iraq in the 1990s as the sanctions crippled the economy. I remember my family sewing our school bags out of rice bags or old jeans and buying one pencil for me and my two siblings to use at school. This wasn’t really a choice, but a necessity as sanctions (hesar) made buying ordinary things difficult. But who should I blame? Saddam Hussein, who dragged Iraq into many wars, or US administrations that sanctioned Iraq heavily in the 1990s in an attempt to topple Saddam by starving his own people?

Everything was blamed on hesar. Children dying, lack of food and medicines, unemployment, absence of quality education, and the lines on peoples faces growing deeper and deeper day by day. This was all the hesar’s fault. Yet, this suffering apparently wasn’t enough.

On Mar. 16, 2003, President George W. Bush gave Saddam and his two sons, Uday and Qusay, 48 hours to leave Iraq or face war.

WAITING FOR THE WAR

My parents could “read the writing on the wall,” as Americans say. After Bush’s announcement, they decided to go to my grandparents’ house since it was safer. Even though their house was also in Baghdad, it was away from the places that could be targeted by the US-led “coalition of the willing.”

The weather was hot and dry as we drove through Baghdad, the world outside sparse and quiet. People seemed to be going through the paces of their normal life. A donkey pulled a cart carrying recyclable goods. A woman walked on the side of the road wearing her long black abaya, carrying a plastic grocery bag in her hand. A couple of kids played soccer in the street. Heading toward the highway, I saw the plumed flame from the Daura oil refinery like a candle. I gazed at the beautiful mosques standing tall under the shafts of the sun while birds flew in groups around the minarets where the imams recited the call for prayers; “Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar.” Listening to the athan five times a day from the speaker’s minarets at any place in Iraq was comforting.

Our arrival at my grandparent’s house was not filled with the usual excitement but instead was focused on one thing: survival. There we were on the verge of yet another war with the United States.

Has your country ever been invaded? Do you know the sounds? The way you can feel them in your body when it happens in your city?

The adults were all very stressed. As we settled down, the men started talking about the current situation and shared their thoughts. My grandfather stated, “The Iraqi streets are in a state of denial. Many people don’t believe that the war is coming.” My uncle protested, “This time it’s going to happen, but Saddam is now threatening that he is going to use weapons of mass destruction, WMD, which could have a big impact on millions of people.” My grandfather explained that he had heard that Saddam was actually going to use weapons of mass destruction if he felt that he was going to lose the fight. My grandfather recalled a rumor about Saddam saying, “Alaia w ala a’adaie” which means “he would use it against his enemy and himself” rather than losing the war. Essentially, the “scorched earth strategy.”

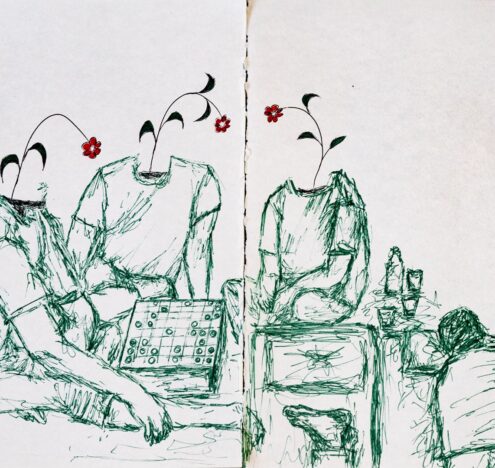

We all sat in the garden during Asr time (the time after noon and sunset) for what seemed like one last time before Iraq changed forever. My grandfather held the radio close to his ear, listening to Radio Monte Carlo. My grandmother brought out the cardamom tea with her freshly baked bread that she used to make regularly while my aunt laid down the plastic mat, the hasira, which every Iraqi house possessed, to sit on. My uncle brought out a couple of mahfas, handmade fans made of palm fronds, which are now becoming increasingly hard to find.

I volunteered to spray the trees with water from the long hose that ran from the main faucet. As I started to spray, the fresh smell of jasmine filled the garden. I then joined everyone and sat on the hasira to have bread and tea, which was something that we usually ate as kids during sanctions. We could hear kids playing soccer outside, a man calling out for his son, and the birds flying in the clear sky. I remember being filled with a strange feeling. Is this what they mean when they say the calm before the storm?

Since this wasn’t our first war, we were very experienced in things like what types of food to stock up on. So, each family member did their job. My grandmother made sure that she bought extra potatoes, dry beans, flour, rice, and oil. My aunt and my mother boxed up the plates from the china cabinet. Meanwhile, my uncles helped each other tape the windows with X-shapes to mitigate the shattering of glass in case of an explosion. They also hung blankets on the windows, especially in the bedrooms and living rooms, since that’s where we spent most of our time. They bought candles and extra kerosene lamps to use during power outages. My grandfather had been filling up the big blue plastic tanks with water and placing them in the bathroom and under the stairs, in case the water was cut and the war went long. But filling up the water tanks and having kerosene lamps was part of our daily life since we regularly experienced power and water shortages.

According to Bush’s deadline, the invasion was hours away. Thinking of it now, what a strange word “deadline” is to use to start an actual invasion that would upend millions of lives. My sister, brother, and I went to pick up the thin mattresses, blankets, and pillows from the baytoona upstairs, a room where our house stuff was stored, to put them on the ground in the bedroom and sleep. We were told to sleep in the room with the fewest windows to be safe from the shelling.

As I prepared to go to sleep that first night, waiting for Bush’s deadline, I observed how tired the adults’ faces were. I realized how each and every war in Iraq had stolen years of our lives. How they had always lived under the strain of the unknown. I remember my grandfather smoking furiously while pacing the kitchen in his white dishdasha (traditional Iraqi menswear that is a long white shirt). He often flipped his shmagh (the red and white men’s scarf) that he wore around his neck as he paced with the radio plastered to one ear to hear any news. My uncles were sitting in the living room discussing possibilities and sharing updates. Their voices peppered the night like birds.

What did the United States bring to Iraq? Certainly not accountability or justice or stability or democracy. Instead, millions of Iraqis were — and remain — displaced.

We lay on our mattresses while my mother and aunt lay beside us, sharing worries. The power was on, but the lights were off, and the door almost shut except for a faint glow penetrating the room’s darkness. That night wasn’t like any I’d ever experienced before. Every minute passed slowly, like molasses. Lizards darted furtively around the room, as if they, too, were standing guard. One in particular had set up shop near our clock and constantly poked his head out from behind the numbers to check on us. It was so strange, and the world was so quiet except for a stray dog barking outside and the clock ticking. It seemed like even the clock showing the time to be 1:05 am was afraid of the future, moving heavily in hopes of delaying the war. I thought of my friends and wondered if they were safe. Then I thought of possibly being hit by a missile.

Would I still be able to attend school after the war? Would I see my friends again? Would Baghdad be very different after this war? It seemed like there were no clear answers to any of my questions. In fact, no one in Iraq knew exactly what would happen next. I looked back at the golden shiny clock. It was only 1:10 am. No one wanted this war, but how long can we delay it? I stayed up all night, thinking and unable to fall asleep.

In the very early hours of the morning, my grandfather pushed the bedroom door wide open and announced with a stressful and loud voice, “Get up, the war has started.”

THE SOUNDS OF WAR

Has your country ever been invaded? Do you know the sounds? The way you can feel them in your body when it happens in your city?

We heard explosions that weren’t yet close. We watched our windows, but they remained intact. Iraqis had expected the war to never start, but it did. Not much happened the first day, though, and later, my mother blamed my grandfather for waking us all up. Like it was nothing, after all.

But the tension in the house grew day by day. We heard sirens all the time. The news reported that the provinces in the south were fighting the Americans and that they hadn’t fallen yet. On the other hand, the news my grandfather heard on the radio was different. His station said the provinces in the south were indeed surrendering, and the US-led coalition was approaching Baghdad. We heard that Saddam’s palaces were bombed. The explosions seemed to be coming closer to us, and the house began to shake.

The Iraqi TV channels were broadcasting the news stating that the war was going just fine and Saddam’s officials held numerous news conferences telling us that Iraq would not yield to the Americans. And artists played their parts as well. The famous singer, Qasim Al Sultan, stood wearing his grey dishdasha, white and black scarves wrapping his head. He held his weapon in his hand while standing in the middle of an army of men who were also holding guns, carrying Saddam’s pictures and the Iraqi flags, praising Saddam and the Iraqi army. “Just go forward to the war and leave it to your men to fight,” sang Al Sultan.

Also, just as Iraqis thought that Saddam was dead during one of the air raids, he appeared in the Adhamiya area, a Sunni-dominated area in Baghdad in the middle of the crowd waving his hands and smiling. Baba Saddam, or father Saddam as he liked Iraqi kids to call him, looked different. There was a rumor circulating that his surgeon had performed plastic surgery on many other men to create his “double” — look-a-likes that would enable him to be in several places at once. This man looked like he could be Saddam’s double, but no one was sure of anything anymore.

This was the nature of war: the terror and uncertainty, the daily mystery of sounds and faces.

BAGHDAD’S FALL

The Americans were dropping bombs everywhere. In the third week of the war, we heard that many members of the Iraqi army who lived nearby had returned. They said that everything had been destroyed, and there was nothing left to fight for. For us, everything indicated that Iraq had lost the war, and we had two options: die by Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction (which many Iraqis believed that Iraq had even though evidence eventually indicated that this was not true) or look toward a sanctions-free future. Opposite ends of an odd spectrum indeed, but one that every Iraqi would be familiar with.

During the last days before the fall of Baghdad, we heard a rumor that Uday’s palace in Radhwaniya area was hit in an air raid. A couple of hours later, my grandfather came running to check the front doors. When he discovered that the kitchen door, which led to the main big house gate, was unlocked, he was furious at everyone for not noticing. He stated, “Don’t you know that Uday’s big lions that he trained to eat humans are now set free?” Human-eating lions set loose in Baghdad may seem like a fantasy but the war was making anything possible.

US forces arrived in Baghdad in the beginning of April 2003. We heard the coalition tried to control the airport and that it wasn’t an easy fight. The news told us the Americans had used weapons that made a whole tank and human dissolve and disappear. On the other hand, the Iraqi military used flour to make it look like they used weapons of mass destruction. According to the returning soldiers, the airport did fall. Yet, the Minister of Information Muhammed Said Al Sahaf reported, “Today we slaughtered them in the airport. They are out of Saddam International Airport” and “The force that was in the airport, this force was destroyed.”

On Apr. 9, 2003, Baghdad fell. In his last appearance, Al Sahaf stood on a bridge in Baghdad and stated, “The Americans are going to surrender or be burned in their tanks. They will surrender, it is they who will surrender.” But in the broadcast, we could see an American tank parked a couple of meters away from him. His claims were so outlandish that he was nicknamed “Baghdad Bob.”

Al Sahaf constantly used the word “uluj,” which is a worm that attaches itself to a body and sucks blood, to describe the US forces that overtook Baghdad — and the whole country. For some, those forces were heroes and marked the beginning of Iraq’s post-Saddam era and democracy, while for others, they were merely invaders.

IRAQ NOW

On May 1, 2003, Bush announced that major combat operations in Iraq had ended. People were happy that Saddam was overthrown after 30 years of dictatorship, while others didn’t express any feelings. I just wondered about my friends and whether they had survived the war or not.

With Saddam gone, I thought this meant no more sanctions. I couldn’t wait to see my father buying us bananas, the real ones. The Americans and their allies promised us Iraqis a better country. I imagined a better school system and buildings where one didn’t suffer from the cold in the winter or the heat in the summer. I wanted to go to school in a building that looked like the ones in America, the ones we saw on television. But, of course, those were false promises.

What did the United States bring to Iraq? Certainly not accountability or justice or stability or democracy. Instead, millions of Iraqis were — and remain — displaced. My family was forced to leave Iraq in 2006 when sectarian violence was at its peak. “Shia” and “Sunni,” two terms that we rarely used, were now part of our daily conversations. Radical groups targeted my Sunni father and Shia mother. After my dad’s cousin was kidnapped, drilled to death, and found in the trash in Baghdad, my parents decided it was not safe to stay there anymore, so we fled.

Our displacement journey is just one story out of thousands, even millions, as 9.2 million Iraqis are refugees worldwide or internally displaced. We left for Syria, where we lived for two years. I finished high school, and my family was granted refugee status in the United States in 2008.

In 2018, I visited Iraq for the first time since I fled to work on a documentary project on life under ISIS in Mosul in northern Iraq. The city has been liberated a few months before I arrived. As I tried to film the reality of Iraq while walking through Mosul, it seemed as if everything had been reduced to rubble. And the smell of death filled the air. My Iraq was not any better than when I had left it 12 years ago at that time.

I returned once again in January 2023. Baghdad is full of life, and every part speaks to a certain time in history. I remembered the Baghdad of the 1990s and reflected on those days in 2003, when the war started. I also visited the National Museum, took a boat ride on the Tigris river, and walked on Al Mutanabi street, a famous street where Iraqis gather to talk, socialize, sing, and, most importantly, buy books.