Marwa Mannaa, tall and soft-spoken, loves school and chatting with her friends. Bubbly, talkative Mariam Mannaa loves listening to K-pop idols BTS and Blackpink; once, she even went to a televised concert at a movie theater in Beirut, she gushes.

“Like the one they did for the Taylor Swift Eras Tour!”

“My friends sometimes tell me, ‘How can you be doing that during a war, while people are dying?’” Mariam tells me on the living room sofa in Hadath, a suburb just south of Beirut. That’s where the 15-year-old twin sisters live with their parents and two older siblings.

It’s Tuesday, Sept. 17, just after 3 p.m.

The girls have felt relatively insulated from the worst of the war since Oct. 7, they tell me. It’s been nearly a year since Israel began its brutal bombardment of Gaza, the West Bank and southern Lebanon, killing more than 40,000 people in Palestine and 600 in Lebanon — children, babies, and teens among them. The fighting has displaced more than 100,000 people have from their homes in Lebanon, the vast majority in the south.

But that’s all miles away from where Mariam and Marwa live. Until this past week, the few direct Israeli attacks on Hezbollah officials in Beirut’s southern suburbs were far enough away from the girls’ apartment building that they weren’t physically harmed.

There are still the jidar as-sowt noises — Israel’s tactic of deploying warplanes to break the sound barrier above Beirut and other parts of Lebanon, creating terrifying sonic booms that sound like bombs. The girls tell me they’re still convinced that they are safe, for the most part.

“My dad just tells us not to be scared when we hear them, it’s nothing,” Mariam says.

It’s nearing 4 p.m. Outside their house, we start to hear a crescendo of ambulance sirens that won’t stop. Something pops up on their cousin’s phone about Hezbollah officials’ pagers catching fire, or perhaps exploding.

We ignore it for the moment, pushing it beneath the surface.

“Didn’t Want That for My Kids”

Kevork Harboyan’s memories of growing up during the Lebanese Civil War come in a series of images. There are the sandbags outside his childhood house. Shooting. The one Christmas his dad stayed distant and quiet, after narrowly escaping a roadside bomb.

At one point, the family fled to Aleppo, Syria, where they stayed for six months. He locks eyes with his son, 14-year-old Veh Christ, from across their living room in a suburb north of Beirut. “Did you know that?”

A round of loud fireworks crackles outside. Instinctively, I check the window.

When I visited Basel Kandeel, another Lebanese father, this past summer, he breathily listed off the succession of wars and occupations to have riled Lebanon in the past 100 or so years. He himself lived through the Civil War from 1975-1990 as well as Israel’s occupation of south Lebanon. He hunkered down at home in southern Beirut during Israel’s month-long bombardment of Lebanon in the summer of 2006.

After the dust cleared, he and others began to marry and have children of their own assuming their kids would grow up free of those traumas. “I didn’t want that for my kids,” Kevork says.

Up until a year ago, they were mostly right.

“Sometimes It Shoots”

But now, Lebanon’s generation of post-2006 babies are coming of age in yet another conflict. Veh says he now can distinguish whether a loud noise is simply an Israeli sonic boom, and he’s no longer afraid of them. Instead, he tries to catch a glimpse of the fighter jets passing by, as he’s obsessed with airplanes and hopes to be a pilot someday. His favorite hobby: spending hours practicing take-off and landing at Frankfurt airport on Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020.

This wasn’t always the case — when I first met him, a year ago, he was still afraid of loud noises, after a stray bullet from a nearby funeral pierced his lung. Veh had been outside playing a football match in the southern Beirut suburbs. It took months of re-training and recovery to get back on the field. Last month, he and his brothers also managed to hike to the top of Mount Ararat, a peak in historic Armenia that he and other Armenians consider sacred.

The bullet will remain lodged in his chest for the rest of his life.

He shrugs off the experience. “I’m pretty much fine, and I can’t feel the bullet anymore.”

So, seemingly, is nine-year-old Julia Hashem, who is much closer to the line of fire — the soon-to-be fifth grader lives with her mom, Fatme Abbas, and dad in Burj al-Shamali, a village near the southern Lebanese city of Tyre.

Though she feels scared and anxious sometimes, she says, “I settle it out by myself. I just forget about it sometimes.” Usually, she draws, planning out animations a la her favorite YouTube channel, “Haminations.”

Still, sometimes that doesn’t work. “The teachers [at school] just tell us to not be afraid if there’s a jidar as-sowt. But there was one really, really loud one once. I was crying so much that I had to leave.” Julia ended up stepping out of class and going home.

An Israeli drone whizzes by as she and Fatme speak to me over the phone. “Did you hear that?” the mom and daughter exclaim. “That was an MK,” Fatme adds. “Sometimes it just takes pictures.”

“Sometimes it shoots.”

The Adults in the Room

Fatme works as a teacher supervisor in the same school as Julia. They don’t have a dedicated school counselor, though one of the teachers, who has some experience in child psychology, helps talk the children through the frightening sounds around them, Fatme says.

“She’ll tell them, ‘It’s okay, that’s just a sonic boom,’” she explains. “When the sonic booms first began, there were kids who cried, and people were scared — including me! But they want us to be scared, so we have to be the opposite.”

It’s a sort of equilibrium the teachers and students have reached after nearly a year of war. When it first began, in October, the children had only just begun school — delayed due to teachers’ strikes and an ongoing countrywide economic crisis.

“We had to close the school until we understood what was going on,” Fatme remembers of that time. “But then when we figured the bombing wasn’t close to us, we reopened as normal.”

Only, things weren’t quite normal. Some students had been displaced from Naqoura, a town right next to the Israeli border. Others left the south altogether, fleeing to Beirut and elsewhere with their families. “They had to study online,” Fatme says. “Their houses were very close to the war.”

“Are They Going to Bomb Beirut?”

In the southern Beirut suburbs, Nisrine has been a high school psychological counselor for the past 10 years. She spoke on condition of a pseudonym as the school hadn’t authorized her to talk with the press. Today’s war is her first as a school counselor, she says, though she has guided students through previous “times of unrest.”

Mostly, the students come to her for help navigating their parents’ divorces or with “friendship issues” and the pressure to get good grades. But she worries the war might have a long-lasting impact on her students’ mental health: “anxiety, PTSD, depression and insecurity,” she lists.

Some children are even forming “attachment issues,” according to Nisrine, clinging to their parents for safety amid the turmoil.

“So after dealing with separation anxiety that younger children normally feel when they are required to be away from their parents for a while, I’ve seen it come back and much stronger even for older kids (9-12).”

Joumana Jaafar is already seeing some of those changes. She’s been a schoolteacher in Lebanon for the past 20 years, though switched to working as a private tutor three years ago. She also runs anxiety management workshops with children, to talk about their emotions and do yoga as a group. I meet her one recent afternoon as she prepares lesson plans in a neat notebook by the seafront.

“I had a student who, whenever we start studying, he pauses. He starts talking about the war,” Jaafar says. “‘Do you know about the war in the south?’ he asks me. ‘Do you think it’s going to come here to Beirut? Are they going to bomb Beirut?’”

She adds, “He’s eight years old.”

Shattered Peace

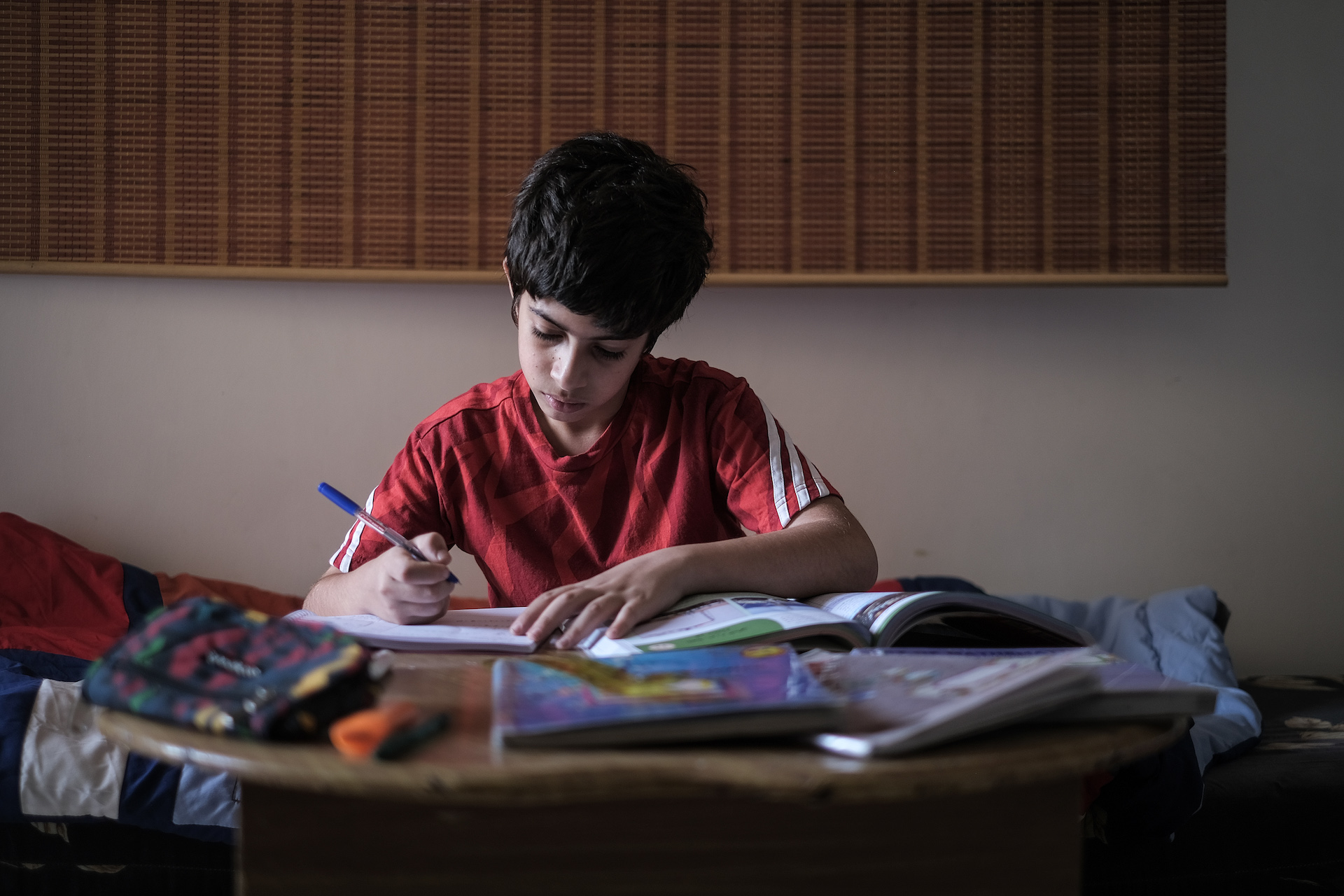

Teenage twins Marwa and Mariam are set to start 10th grade in the coming days, at a nearby school in the southern Beirut suburbs.

They say they are still somewhat safe in their neighborhood. They go to the movies and the pool with their friends and relatives — though don’t wander off too far in case anything happens.

Just half an hour into our conversation, my colleague walks into the room staring into his phone: apparently, the burning pagers problem we heard about is bigger than we all thought. Soon we’ll learn that thousands of people have been injured in the Israeli attack.

Booby-trapped pagers in Hezbollah members’ pockets, homes and cars reportedly beeped and then detonated across the country, in an unprecedented attack that the UN and rights watchdogs say is contrary to international humanitarian law.

Many of the attacks were just steps from the Marwa and Mariam’s home in Hadath.

A dozen people will die that same day, Tuesday, including two children. One of them, nine-year-old Fatima Abdullah, was simply handing her father’s pager to him after it started beeping at home in their village of Saraeen, eastern Lebanon, according to The New York Times. It exploded as she carried it, just hours after her first day of the school year. She was the same age as Julia.

Among the injured are several members of Marwa and Mariam’s own family, I’ll later learn. The next day, Wednesday, more will die and be injured in yet another round of explosions on walkie-talkies and other communication devices. The death count is 32 by Thursday, according to the health ministry.

“This Isn’t Normal”

On Friday, the violence will claim more children: Israeli strikes on a densely populated area in the nearby Haret Hreik neighborhood will kill 50 people, including toddlers, who had simply been at home during a high-level Hezbollah meeting under target by Tel Aviv.

For now, though, as we sit together on Tuesday afternoon, the two girls don’t know all that yet.

I playact at being calm, ask about K-pop and their friends, about school. We pause so they can check on their friends over Whatsapp. The siren sounds grow.

“This one always messages me as soon as something happens, and she’s not answering me!” Mariam says, trying to reach one of her best friends. “This isn’t normal.”

Just downstairs, ambulances and cars packed with the wounded rush to hospital.

** All photos by João Sousa. Sousa is a photojournalist based in Lebanon and focused on social issues.