Ever scrolled through your social media feeds and wondered how the latest art, culture trends or memes are connected to national security and foreign policy? We have! So, we introduce to you our new column: The Mixed-up Files of Inkstick Media (inspired by From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler), an outlet for us to explore whatever cultural phenomena, sometimes heavy and sometimes light, that is shaping the way we look at and live in this world. This new column will come out once a month and feature articles from Lovely Umayam and Molly Hurley.

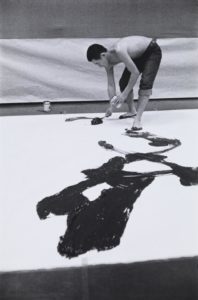

Art can give death and anxiety a definite shape. In the 1950s, artists threw glass bottles of paint on paper sprawled across the floor as a visual response to the Cold War and the Atomic Age. Drips and splatter of color became portraits of the invisible yet palpable fear that the next nuclear attack could trigger the end of the world. A Japanese painter at the time, Kazuo Shiraga, pushed this concept further. For a series of paintings, Shiraga dangled a rope on the ceiling, held it with his hands, and stepped on the canvas to paint with his bare feet. The resulting work reflected the spirit of his generation: The harsh strokes of black and red pigments mimicked debris after a bombing, or deep wounds on flesh.

Shiraga was a member of the Japanese avant-garde group “Gutai,” a word that loosely translates to “concreteness.” The Gutai cultivated a talented group of artists, all of whom came of age during the carpet bombing of Tokyo, and the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. They were enthralled by the idea of decay — the way matter withers from the natural passage of time, or torn apart by a singular flash of disaster to reveal its purest state. Gutai artists wrestled with mud, burned wooden planks, stabbed paper, and mixed chemicals until they fizzed into flamboyant arcs. Gestures that gave anger and grief tangible form.

I wonder how the Gutai’s credo translates to today’s version of devastation and decay. There is no material imprint of the COVID-19 and its variants: The rising number of the hospitalized and the dead — figures that once anchored us to the sobering reality of the pandemic — are beginning to fade in the backdrop of our new routines. And in the throes of a pandemic, police murdered Black people, strangers attacked Asian elders, a mob breached the US Capitol grounds, fires ravaged forests, and hurricanes sliced through coastlines. While real to those whose bodies, homes, and livelihoods have been destroyed, these crises often reach the world as bytes converted into pixels on computer screens. I, along with everyone else watching, partake in digital grief — an outpouring of emotion detached from concrete experience.

As we watch these tragedies unfold online, the lack of physicality takes away the depth of experience and our understanding of groundtruth. We enter the digital ether seeking to empathize, but we come out feeling more contrived and tired.

In his essay “Death in the Browser Tab,” Teju Cole writes, “A video introduces new elements into the event it records.” Capturing the moment of death with such precision risks blurring the boundaries dividing truth from spectacle. “The star is likely to be death itself and not the human who dies.” Once tragedy is uploaded online, it spreads like contagion, appearing on all platforms instantaneously, and playing on repeat for billions of people to watch from afar. This simultaneous experience of proximity and distance, of connection and detachment, is how the world felt the tremors of Beirut.

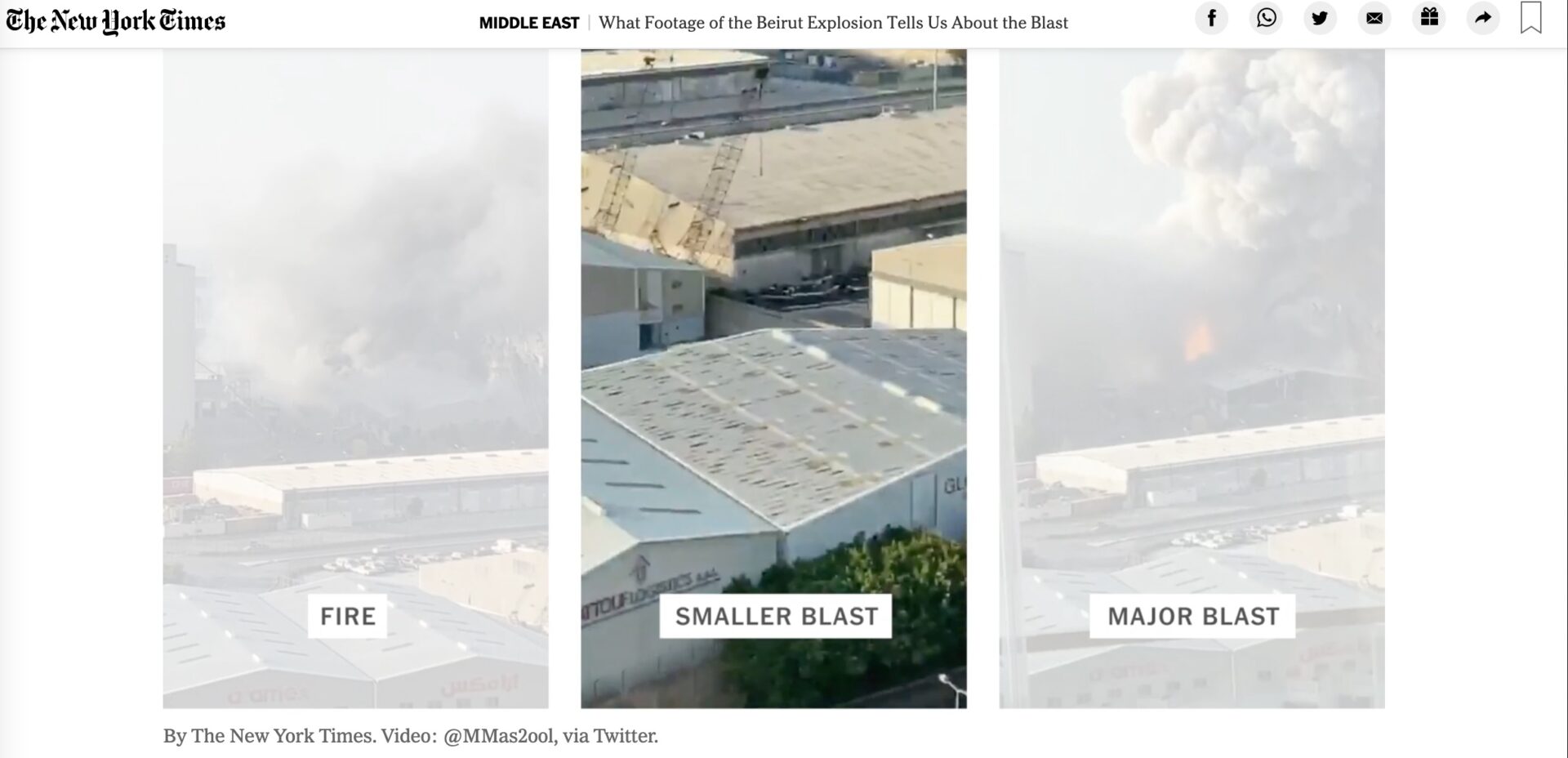

In the afternoon of August 4, 2020, a fire appeared in the port of Beirut, consuming a warehouse on the water’s edge. The fire morphed into an angry column of smoke, catching the attention of passersby who instinctively reached for their phones to film the scene. Without warning, the fire exploded. A cloud of debris and overpressure barreled through the streets, flattening everything in its path. A few days later, the Lebanese government revealed the culprit: Abandoned ammonium nitrate, a chemical ingredient found in fertilizers and bombs. The chemicals sat idly at the port for six years as politicians shuffled paperwork to determine what to do. The source of this tragedy is frustratingly immaterial. How does one grab ineffective, negligent bureaucracy by the neck? Or punish wasted time?