Early on August 30, 1945, a Japanese Army Captain escorted Fritz Bilfinger through a lunar streetscape littered with “carloads of dead bodies.” Twenty-three days earlier, the world’s first atom bomb had detonated 2,000 feet above the Nakajima business district at 8:15 on a clear-skied Monday morning. He was the first Westerner to step foot in the new-broken city of Hiroshima.

Bilfinger was no stranger to horror. He had spent the previous sixteen months traveling in Japan and Manchuria, advocating for the treatment of American, British, and Chinese prisoners-of-war according to the Geneva Conventions as a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The prison camps of the Kwantung Army and the daily American bomber raids on defenseless Japanese cities, including the firebombing of Tokyo that had killed or injured nearly 200,000 the previous March, had not prepared him for what he saw in the once-bustling regional capital. In the seventy-five years since the Second World War morphed into a nuclear war, humanity has struggled to reckon with the Carthaginian scene that greeted him that day.

It was a plea from Japanese Emperor Hirohito that set Bilfinger off on his journey. The forty-four-year-old Son of Heaven had issued a formal complaint to the Geneva-based International Committee of the Red Cross six days after the bombing that the indiscriminate, wanton, cruel nature of this new weapon had breached the spirit if not the letter of the laws of war.

Three days later, Hirohito announced his nation’s surrender — over the radio. It was the first time the Japanese people had heard their emperor speak, for fear that such a material act would spoil the metaphysical bonds that bound the Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere together.

After Bilfinger read of the communiqué in Japanese newspapers, he convinced Marcel Junod, the Red Cross chief delegate, to let him corroborate the emperor’s allegations. Bilfinger embarked for Hiroshima from Osaka, where just a few days earlier US B-29s had flattened Kyobashi Station with two full passenger trains sitting at their platforms, touring two soon-to-be-liberated POW camps along the way, before arriving on the dead city’s outskirts early on August 29.

He walked into a wasteland. Radiating outward from the hypocenter — the point on the Earth below the center of the three-football-fields-wide fireball — near where the Ōta River flowed beneath the Aioi Bridge before splitting into the Kyōbashi and the Motoyasu rivers, an inner circle two kilometers in diameter was “totally destroyed,” with houses for another four kilometers “greatly damaged,” and many as far as ten kilometers from ground zero battered.

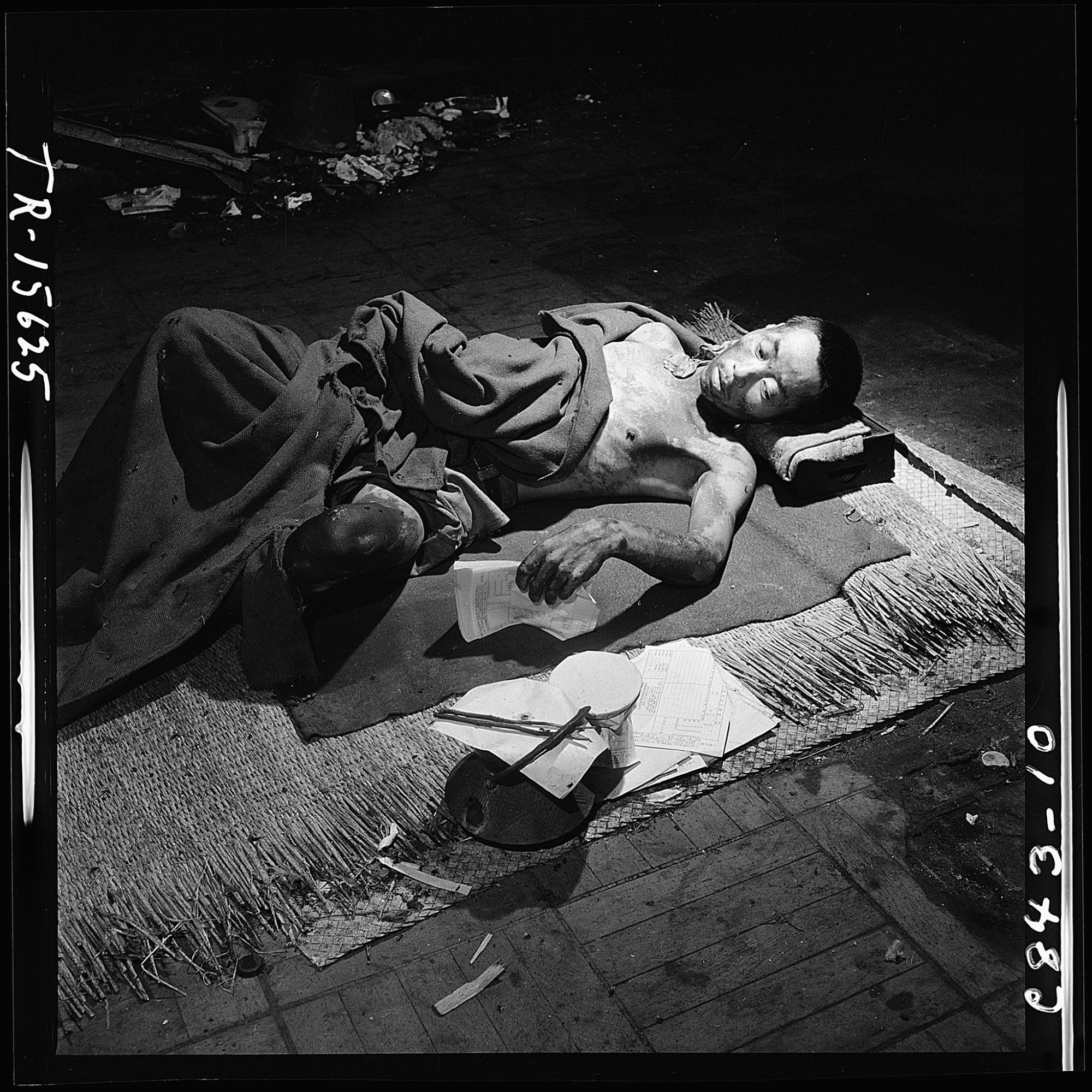

It was the toll on the city’s healers, however, that concerned him the most. Only two medical centers were standing: an emergency surgery and the Red Cross hospital one mile from Aioi Bridge, which had miraculously survived the blast wave, and where a few score doctors and nurses tended to thousands of survivors, most suffering third-degree burns across their bodies, many left blind by the blast’s unearthly brilliance, thousands rapidly succumbing to what medics could not know was radiation sickness. He sent a telegram to Junod straightaway:

Visited Hiroshima… conditions appalling. City wiped out, eighty percent all hospitals destroyed or seriously damaged. Inspected two emergency hospitals, conditions beyond description. Effect of bomb mysteriously serious, many victims apparently recovering suddenly suffer fatal relapse due to decomposition to white blood cells and other internal injuries, now dying in great numbers. Estimated still over 100,000 wounded… sadly lacking bandaging materials or medicines. Please solemnly appeal to allied high command to consider immediate airdrop of relief action over center city.

Medical supplies and trained healers were in “dire need.” Two months later, he remembered conditions at Horikawa Emergency Hospital as “surpassing all imagination.” It had “looked more like a morgue than an emergency hospital,” he recalled. He assured Junod on August 31 that his account was “not at all exaggerated,” and urged him to visit himself “at the earliest opportunity.”

No city should stand as a metonym for atrocity. Japan’s capitulation and the Cold War that ensued transformed what happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki — tragic events with life and death stakes — into phenomena bereft of meaning, stripped for data points.

No city should stand as a metonym for atrocity. Japan’s capitulation and the Cold War that ensued transformed what happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki — tragic events with life and death stakes — into phenomena bereft of meaning, stripped for data points. Humankind’s most dreadful handiwork was rechristened a revolutionary guarantor of peace among nations.

The flesh-and-blood significance of the bombings has endured thanks to elegies written by humanitarians like John Hersey, whose powerful “Hiroshima” appeared in The New Yorker one year after the attacks, by the Japanese survivors (known as “hibakusha”) like Captain Shishido, the man who accompanied Bilfinger on his walk, whose ranks dwindle every year, and by abolitionists, ranging from Ronald Reagan and his surprising pursuit of nuclear disarmament with Mikhail Gorbachev to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and the 2017 UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which denounces on grounds of inhumanity these weapons that leave behind “superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.”

Witnesses to Hiroshima unleashed a contagion of empathy that started as soon as Bilfinger’s telegram reached Junod in the Marunouchi district of Tokyo on September 2 — the same day that General Douglas MacArthur accepted Japan’s formal surrender on board the USS Missouri. Junod raced across town to petition the US Supreme Allied Command at the Yokohama Chamber of Commerce for food and medical relief. Within days, MacArthur had dispatched twelve tons of supplies in boxes adorned with the Red Cross emblem.

Three days later, the International Committee of the Red Cross became the first nongovernmental organization to comment on the bombings. The custodians of the Geneva Conventions called on the victorious United Nations to revise international humanitarian law so that the new forces of “totalitarian war” could be tamed, lest their “destruction unlimited” reduce to ash the humanitarian ideals that upheld “the intrinsic worth and dignity of people.”

In his final report, Bilfinger enjoined the broader Red Cross movement to do their utmost “to have the use of atomic power as a destructive force outlawed.” Junod was likeminded. After he toured the irradiated “necropolis,” he underscored how the Bomb’s “supernatural force” had broken down the civilizational wall that separated man from beast — so important in the Christian theodicy that had inspired the humanitarian movement. What did it mean for a weapon to exist capable of snuffing out “thousands of human beings… like flies.”

Professor Masao Tsuzuki, the Japanese biologist who accompanied him on the excursion, compared the unsuspecting victims to the animals on which he carried out his radiation experiments: “Yesterday it was rabbits; today it’s Japanese.”

Tsuzuki was prophetic. The lives of the hibakusha would become the most forensically analyzed in human history. Longitudinal studies carried out by the US and Japanese governments and independent scientists from 1947 to the present have found that survivors were 10% more likely to develop cancer, with rates skyrocketing to 44% among the most heavily irradiated. If you were fortunate enough to leave Horikawa Emergency or the Red Cross Hospital, you could expect to live 1.3 fewer years than those who lived ten miles up the road.

Like the radioisotopes that poisoned the hibakusha, images of the prodigious suffering at Hiroshima and Nagasaki would radiate out, embedding themselves in the global culture that arose from the ruins of the Second World War and its indelible lesson — “Never Again.”

US President Harry Truman, upon learning of the second bombing at Nagasaki on August 9, recoiled, not having realized it would go forward without his direct order. He established that from that day forward only the president could authorize such acts of mass death.

Hersey wove together the stories of six survivors’ in The New Yorker one year later to personify the moral magnitude of the “Little Boy,” shattering the consensus in American life that atomic violence had wrought justice for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the Bataan Death March. To the extent these stories had a resolution, it was the survivors’ arrival at the overwhelmed Red Cross hospital among throngs of shell-shocked victims. He refused to profit from the piece, donating all proceeds from the standalone issue to the American Red Cross.

Even the Pentagon has proved susceptible to moral arguments. For decades, civilian officials waged a campaign within the Department of Defense to add options in US Strategic Command’s targeting packages besides what nuclear strategist Herman Kahn once styled the “wargasm” of all-out thermonuclear war.

Also like radioactive isotopes, however, these impressions have had half-lives and quantum valences. In the decades since the world first witnessed what Don DeLillo referred to as “the sun’s own heat that swallows cities,” every nuclear-weapons state is modernizing, enlarging, and diversifying its arsenal. Since 2003, three cornerstone agreements — the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the 1992 Open Skies Treaty — have all fallen into history’s dustbin. The 2011 New START Treaty, the sole remaining arms control treaty binding the United States and the Russian Federation, may be next.

The options for waging limited nuclear wars, which might arguably meet the most charitable humanitarian criteria, are also multiplying. On August 1, British Defense Secretary Ben Wallace publicly urged the US Congress to fund a new, low-yield Trident warhead whose operating characteristics are practically optimized for triggering a spiral of nuclear escalation.

Seventy-five years since catastrophe befell Hiroshima, humanitarian ideals remain inspirational. In the face of this new, many-sided arms race, however, they may not be enough.

The Red Cross, of all institutions, learned this early. For years, the international organization had acquiesced to nuclear powers’ claims that formal bans would erode the credibility of their deterrents, rendering atomic conflict more, not less, likely. In essence, the world’s foremost humanitarians refused to deem these weapons “evil-in-themselves.” Then, in 2011, fifteen years after the International Court of Justice punted on “whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which the very survival of a State would be at stake,” the movement went bravely beyond established law, embracing a prohibition on the use and even the possession of nuclear weaponry.

Bilfinger and Junod would have been proud. The ghosts of Hiroshima, by contrast, remain silent. Every day they haunt us less and less.

Dr. Jonathan Hunt is a lecturer in modern global history at the University of Southampton. He is the co-editor of The Reagan Moment: America and the World in the 1980s, with Dr. Simon Miles, and the author of a book manuscript on the history of nuclear nonproliferation, Atomic Reaction: The Nuclear Revolution and America’s New Global Mission, 1945-1970.