“My brother was wounded a few months ago near Bakhmut,” Liubov Halan said, “His leg was amputated, so most likely, when he gets discharged from the army, he’ll become the target audience for my organization.”

“Going on this journey with him, I realized we had to redo lots of things to serve people like him better,” she added.

Liubov Halan is a co-creator and a head of the human rights center “Pryncyp.” Launched in early 2023, “Pryncyp” (or “Principle” in English) is a new initiative that lobbies for the rights of veterans in Ukraine. It addresses systematic issues that prevent veterans from receiving the services guaranteed by the state and that need to be resolved on a national level.

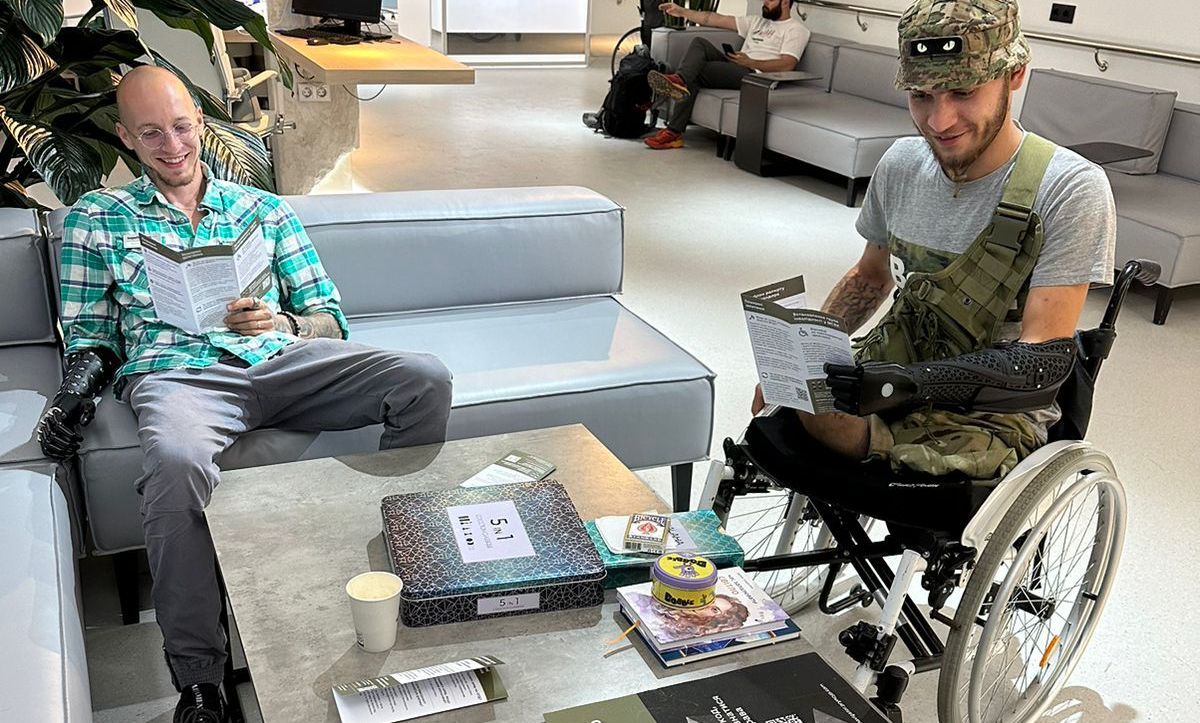

Currently, Ukraine has around 1 million active soldiers, and by the end of the Russian-Ukrainian war, it is predicted to get around 1.6 million veterans, many with disabilities. While the state guarantees free prosthetics and rehabilitation services to the soldiers, many of these things exist only on paper as there are no funds or infrastructure to provide them.

Liubov and her team are tackling these problems by advocating for profound changes at the institutional level and by simplifying bureaucracy and legal language for veterans and their families.

“We Are a Mirror of the Veterans’ Reality.”

In 2022, Liubov quit her job in the UN system. She said she “wanted to do something that would help make the state capable of surviving this war and fighting against genocide.” At the time Liubov was doing a lot of volunteering, so when her friend proposed the idea of creating “Pryncyp,” she said it felt like “salvation.”

This, in a nutshell, is how “Pryncyp” started. Masi Nayyem, a renowned Ukrainian lawyer, approached Liubov in the fall of 2022, and proposed launching an organization that would serve veterans. Nayyem is a veteran himself — he joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces in 2015 and fought in the East. In 2022, he returned to the army amid Russian full-scale invasion, and was badly wounded in June of that year, losing an eye.

The injury made Nayeem experience the bureaucracy and veterans’ struggles firsthand. As a lawyer with years of civil activism, he decided to lobby for a change on an institutional level.

“Right away, we decided to focus on advocacy instead of individual legal aid,” Liubov explained, “We realized that even if there are many great lawyers in Ukraine helping veterans, they won’t be able to improve things for the entire community because they’d keep on working in this flawed legal framework. So we focused on that instead.”

The team that works with Liubov and Masi is a cluster of lawyers, analysts, and project managers, most of whom also share an activist background.

“Our organization — just like the country — is a mirror of the veterans’ reality,” Liubov continued, “Many of our team members, myself included, have close relatives who are veterans or serving in the army. Many of our friends or family have survived after getting wounded. This experience influences our work and culture.”

“Yet, we balance these personal connections with data and evidence,” she added, “We want to serve the veterans’ community as a whole, so we want to know a veteran’s journey and help make it easier for them.”

Access Problems

“Our focus is on veterans with disabilities, who need information and advocacy for changes on their behalf,” Liubov said.

The first step for this is gathering data. “Pryncyp” gathered information from the veterans and their families who described their experiences of visiting different state institutions and asking for services that were guaranteed to them. Based on that, the team tried to map out the veteran’s journey and address its key struggles.

“Right now, there are few soldiers who get released from serving in the army, and it’s mostly after getting wounded,” Liubov said, “So the veteran audience is rather small at the moment. However, it is going to grow to at least 1.5 million people when the war ends, and if we include the family members of the veterans, we’re talking about three million people. This is huge.”

“Knowing this means we have to work on solutions for them for the future,” she continued, “This also involves finding systemic answers on how an individual in Ukraine can get access to concrete services and information about them. For this, we need to study veterans, their paths, and how to deliver the aid to them.”

Russia has been at war with Ukraine since 2014; however, throughout this period, the Ukrainian government did not develop effective veteran policies. Before 2022, the number of veterans was much smaller; after the full-scale invasion, a large influx of veterans is putting pressure on an already vulnerable healthcare system and other infrastructure.

“The law about the veterans is outdated, and it is not backed by finances,” Liubov said, “Basically, it’s full of empty promises about services and benefits, which do not have material support. So, on one hand, there is a lack of systemic changes in the veteran policies, and on the other hand, we have an underdeveloped infrastructure in terms of healthcare and social protection.”

Veteran policies are implemented via the Ministry of Social Policies, the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs, and local communities. If these stakeholders don’t deliver, then it’s hard for civil society to change much.

“Even if you develop amazing solutions as helpers for veterans, these will not work because there won’t be a practical, institutional, and infrastructural backing,” Liubov explained, “This complicates matters.”

Providing Access When It’s Needed Most

Even if services are provided, many veterans don’t know where to get them. It takes a lot of time and effort to get the official veteran status as one needs to collect many documents and visit different institutions — which is a major challenge for someone who’s just returned from the war zone and who may be struggling physically and mentally.

Family members struggle, too. As most veterans are men, it’s usually up to women — wives and mothers — to accompany their loved ones after leaving the army. They often cover the functions of medics, social workers, and management in addition to their daily jobs and duties.

To help with this, “Pryncyp” developed a legal navigator. It’s a self-help app for wounded veterans and their families, which explains what to do in specific cases when requesting different services.

“There is a huge gap between the law and the reality,” Liubov said, “Our navigator explains what the law says, and what the practice looks like. It considers your background and status guiding on what to do in a specific situation that applies to you.”

The navigator also helps social workers and other stakeholders on the other side of the equation. While they are the ones responsible for providing some services, but they, too, often struggle to grasp what to do and how.

“Our first target was involving more hospitals,” Liubov explained, “But now, we work with community leaders because this is where people seek help and support and where they often face a lack of understanding on what to do next.”

As most veterans are men, it’s usually up to women — wives and mothers — to accompany their loved ones after leaving the army. They often cover the functions of medics, social workers, and management in addition to their daily jobs and duties.

Another big challenge that “Pryncyp” is addressing is integrating veterans as they return to civilian life. The Ukrainian economy shrunk in half amid the Russian war, and few veterans, especially those with disabilities, manage to get well-paid or stable jobs after service. There are some successful cases, however — such as the state Ukrainian Railways company, which retrains veterans and provides them with opportunities based on their capacities. However, more needs to be done.

“We cannot use foreign examples for veterans’ integration hoping that these will work like magic,” Liubov signed. “Unlike many countries abroad, we don’t have as many resources. We have at least one million people fighting, which is beyond anything in the experience of neighboring countries. We are in a state of war and mobilization, so we must develop a system that would work for Ukraine.”

Despite the strain on resources, mass mobilization, and a following influx of veterans served as a catalyst for major changes in Ukraine. The majority of Ukrainians either serve or have someone they know in the army — which makes the issue of soldiers’ and veterans’ rights much timelier and more popular.

“There is a strong political will and a great initiative of various stakeholders to address the issues we are raising,” Liubov concluded, “So the advocacy that we’re doing will be decisive for veteran policies in Ukraine in the following years.”