Many residents fled the city of more than 700,000 since the war began, but those who stay are finding solace in resisting Russian colonialism.

“Before, we were using just what Russia gave us in art and music,” Vakunov said as he showed me around different large rooms the collective plans to renovate for community activities. “Now, there’s a boom in Ukrainian music and culture, and it really works. Many more people started singing (in Ukrainian). We are separate (people). We have everything that we need in us. Not somewhere in (Russia).”

Indeed, nearly 8 million people have fled Ukraine since Russia invaded in February 2022. But for those who choose to stay, living in constant fear is not an option. Vakunov walked me from floor to floor, showing me rooms that are in desperate need of renovation, but that’s the point: They will be renovated.

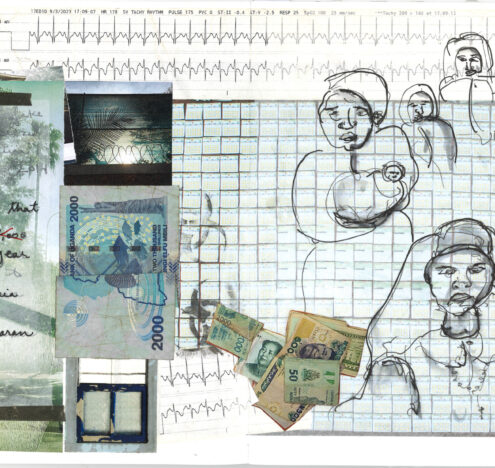

He showed me one expansive space he said would be an art gallery. The bright sun beamed intensely through the broken windows hit by Russian missile strikes from the following fall. People in Zaporizhzhia, and Ukraine in general, are aware that much of the Western media coverage of their country is of people in agony and pain. Vakunov made a point of telling me that the media reports we see in the West hardly reflect the spirit of the people.

Everyone has their own way of coping with the trauma of war here in Ukraine.

“We’re still living life,” he said. “Not like before because the war changed everything. Missiles change your mind when they come to your city and the places you’re working every day. It’s dangerous to work in these places, but you understand that you should live and keep life in the city.”

Vakunov explained that art defines a people’s culture and that centuries of Russian colonialism has harmed Ukrainian creative thought. But the war has made many artists ditch Russian and resurrect their Ukrainian to embrace their nation’s literature. Ukrainians have also spoken out against what they said have been Russian attempts to present Ukrainian artists as Russian. Russian President Vladimir Putin wanted to make Ukraine a Russian oblast. Ukrainians resisted and dug deeper into their own cultural roots instead.

An engineer during his day job and a concert promoter as his side gig, Vakunov said that Meleen Creative Platform provides a space for artists to build an artistic community and resist Russian cultural influence. Before the war, the platform members came together to forge something of a regional renaissance of Ukrainian artistry. Vakunov told me that many Ukrainians in Zaporizhzhia, in addition to not speaking their mother tongue of Ukrainian, were also trapped in the practice of honoring Russian artists instead of their own.

The war has changed all of that.

“We’re just trying to show people that we are not Russia,” he said. “Many of our Ukrainian artists were taken by Russia. They were even killed and repressed by the Soviet government. That’s why we should show everyone that Ukrainians are not a small part of Russia. We are a separate country with our own artists, musicians with a culture much richer than Russia.”

Alona Zakharova, a ceramics artist whose pottery work lines the wall in a small room where she creates her art, shared those sentiments when I met her on another floor where she was working. She has been part of the project since the fall and has never left the city. She reflected on the fact that while many people have left Zaporizhzhia, several internally displaced people from the worst-hit or occupied areas of Ukraine have replaced them.