I was a freshly minted four-year-old on the morning of September 11, 2001. There’s not much I remember about that day, except a flash — I’m in my elderly neighbors’ kitchen in northern Wisconsin, sun washing through the windows, when a breaking news alert comes across the screen of the tiny cube television. My neighbor Dorothy watches with wide eyes, her hands quivering around her cup of tea. The teacup clinks against its ceramic saucer, some of the tea spilling over the sides like the early tremors of an earthquake. “I think you should go home,” she says in my recollection, with the kind of understated gravity usually reserved for the movies.

It seems odd that I still remember these inconsequential details, yet I have no recollection of anything that followed. As a child, I couldn’t possibly have comprehended how this morning in my neighbor’s kitchen would fundamentally change the shape of the modern world and America’s behavior within it. Yet, at some level, I must have known this memory was important enough to keep.

I’m not alone in this sense. The attacks of 9/11 are perhaps the most salient example of a flashbulb memory — an exceptionally vivid “snapshot” of the moments and circumstances in which a piece of shocking, consequential news is heard. Flashbulb memories are distinct from standard memories of historic events or personal experiences of trauma, in part because flashbulb memories aren’t necessarily concerned with memory of the event itself. Very few people saw the attacks in person, survived the collapse of the World Trade Center, or lost a loved one on the hijacked plane. Flashbulb memories are less about experiencing an event and more about the perception of it — remembering who told you, where you were, and what you were doing when you heard the news.

Most Americans born, say, before 1997 have clear answers to the question: Do you remember where you were when the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks occurred? It’s the natural starting point for any conversation about 9/11. In a political landscape often obsessed with the strategic, rational, and quantitative, conversations about 9/11 are unique in that they’re almost always initially framed around the personal and emotional — even twenty years later.

FLASHBULB MEMORIES

The term “flashbulb memory” was coined in 1977 by psychologists Roger Brown and James Kulik, although the phenomenon was known before then. Event memories of Pearl Harbor, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the Challenger crash, have all produced similar shared recollections. Since Brown and Kulik’s initial study, decades of researchers have sought to make sense of this uniquely powerful kind of memory, yet it’s still unclear which specific neural mechanisms can shape and trigger them.

In thinking about why the American public has collectively held onto memories of 9/11, I’m less concerned with the mechanisms that facilitate memory production and retention and instead find myself interested in their larger emotional purpose.

The types of details preserved in flashbulb memories are inherently self-centered. People who survived 9/11 or directly experienced the attacks mostly remember the event through the lens of trauma. But everyone else can only remember details secondhand. Like toddlers with toys, these memories exhibit a kind of object permanence. The events are meaningfully real only when they enter one’s perception. I remember the details of where I was, who told me, what I was doing when I heard the news. Either it’s a subconscious masterclass in making someone else’s pain about myself, or it’s as if my mind is saying that pain cannot exist in the world unless it directly affects me.

But in another more optimistic sense, flashbulb memories are an act of radical, large scale empathy — a collective response to a trauma so massive that it cannot possibly be shouldered only by those who experienced it firsthand. Those who share these memories comprise a sort of imagined community that bridges the gaps between “them” and “me,” instead forming an abstract “us.” When “we” hold onto trivial, unimportant details of these events, we’re holding permanent space in our memory for the pain of those who suffered. It’s a response to the feelings of helplessness and insecurity that so many Americans experienced after the attacks — as if saying, I can’t do much, but the least I can do is remember.

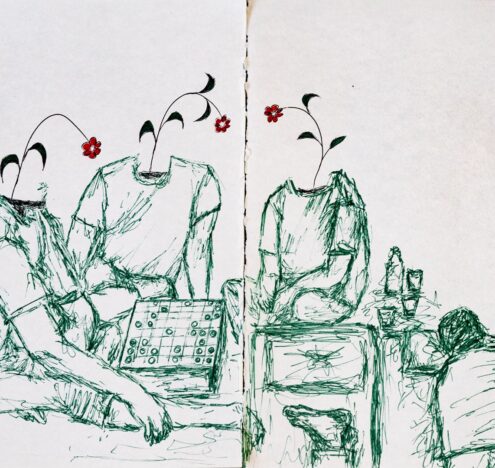

This act of instant and spontaneous collective preservation is a uniquely powerful emotional force, and a testament to just how horrifying the attacks were. However, this kind of memory is limited in the types of emotions and experiences it can capture. Flashbulb memories are named for old-fashioned cameras, partly because the vividness of these memories makes them feel almost photographic. But the term is also used because it’s meant to describe capturing an entire scene in an instant. Since these memories are triggered by shocking, singular events, they cannot capture slow-burning tragedy or abstracted webs of consequence.

Thus, there is a long list of post-9/11 consequences these memories cannot capture, including the civilians killed, injured, or displaced by the US invasion of Afghanistan and the Global War on Terror (GWOT) that followed; the destabilizing ripple effects of American military operations, particularly in the Middle East; the impact of these wars on the lives of women and girls; torture and war crimes; Islamophobic hate crimes; the PTSD of veterans who have served in forever wars, or the grief of those who have lost loved ones in combat. The list continues.

When “we” remember 9/11, we remember a flash of details and emotion, but we cannot, in that same instant, preserve the long, winding legacy of violence born from the American response to these attacks. We cannot possibly comprehend, let alone remember, the consequences of the GWOT in a single moment, seen through a single camera’s lens.

As a result, flashbulb memories facilitate a convenient, stunted kind of empathy — reserved only for those whose pain is directly relevant to ourselves and our perceptions. They can capture in-group pain, but they obscure the pain that has been inflicted unto others. For most Americans, “our” 9/11 memories prevent us from reckoning with what America has wrought.

MOMENTS OF RECKONING

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan is a unique exercise in memory and reckoning. Rarely are we afforded the opportunity to trace complex problems back to a single point of origin. Twenty years after the initial invasion, it’s hard not to reflect on how this war started in the first place, often prompting the difficult question: was all of this worth it?

This reckoning has produced feelings of grief, heartbreak, frustration, and anger among many Americans — although perhaps there’s none more troubling than the feeling that the War in Afghanistan wasn’t just devastating, but a waste. America’s national security mindset is based on an underlying assumption of rationality. When there are precious lives and trillions in taxpayer dollars on the line, there’s the hope that most of what we do is, in the end, “worth it.”

Memories, especially those of 9/11, play an important role in measuring and cultivating this feeling of justification — that the War in Afghanistan was indeed “worth it.” However, despite how strong these memories may seem, they might be misleading.

Although the name suggests a photographic level of recollection, in reality, flashbulb memories are about as accurate as any other memory — which is to say, highly imperfect. Memory is a malleable, slippery substance that shifts and changes with new information and the benefit of hindsight. Each time the brain is asked to recall this memory, it must reconstruct the details, which opens an opportunity for new information to creep in.

What differentiates flashbulb memories from standard ones is not their accuracy, but the level of confidence placed in their accuracy. Because these memories feel so vivid, we are convinced we remember what happened as it truly was — but really, we only remember how it made us feel.

My own flashbulb memory — Dorothy’s kitchen, the breaking news alert, the shaking teacup, the ominous foreshadowing — has always felt true to me, but the more I think about it, the more I notice details that don’t quite add up. September 11, 2001 was a Tuesday, and at that age and time, I should have been at pre-school. Was I really in Dorothy’s kitchen, or is this a detail I’ve subconsciously added in hindsight? Once I see this initial crack, it’s hard to not doubt the rest of my story. Did Dorothy’s wrinkled hands really shake? Was she really drinking tea? Did she really deliver that gut-punch cinematic line? Is this really my memory of 9/11, or is this just how I want to remember it?

There’s no way of knowing what my true memory is, or if I remembered it at all. But it’s worth exploring why I feel the need to remember it in this particular way. Dorothy’s kitchen was a second home to me — a place where I felt protected and loved. To see Dorothy physically tremble, her teacup clinking against the ceramic plate, tea spilling over the edges, made visible deep feelings of vulnerability and a disruption of my childhood sense of security.

Maybe I’ve subconsciously shaped my recollection this way — with suspense, foreshadowing, and gravitas — because I’m taking part in a post-hoc justification for all that has been done in response to this memory.

By continuing to frame larger discussions of 9/11 through this lens of emotion and memory, maybe we all want to remember the post-9/11 American project as better than it really was, or as justified for what it was. For if it’s not, then our behavior is unjustifiable — it’s reckless, cruel, or a waste.

It’s not yet apparent which events of the past twenty years will have the same memory impact for the next generation. A few examples come to mind — Sandy Hook, the election of Donald Trump, the Black Lives Matter movement, the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol, and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, to name a few.

We’re all a little stained by the memories we share. Which ones we keep, and the form in which we preserve them, will undoubtedly shape how Americans conceive of their place in the world — and what we’re willing to sacrifice to secure it.

Megan DuBois is a research assistant in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“The Long Tunnel” is a series of articles reflecting on the impact of Sept. 11 and how it has shaped the world we live in today. You can read more in the series here.