Freedom smells like McDowell’s! Yes, you read it right — McDowell’s — a McDonald’s knockoff brand depicted in the Coming to America movie, which I grew up watching on repeat via good ole VHS tape. A very distinct aroma of grease permeated the customs and border protection area when I landed in America from Turkmenistan, emanating from the McDonald’s located in the arrivals area. The aroma of french fries and grilled burger patties, which lingered in my hair and clothes long after leaving the airport, is the smell of dreams, freedom, and possibility for me.

Prince Akeem, the main protagonist of “Coming to America” left behind a pampered lifestyle in Zamunda and came to the United States pretending to be a poor international student in the hopes of finding love beyond royal titles. Unlike Akeem, I did not need to pretend to be a poor international student — I was one. And while Akeem came to the United States to find genuine love, I fled from an arranged marriage, economic vulnerability, and lack of opportunity. I was running to the land of the free in search of education, gender equality, freedom, agency, equal opportunities, and choice. I also wanted to realize my American Dream of building a career in multilateral institutions, many of which happen to be nestled in New York City.

As I strived to achieve my American Dream, what followed was a series of arduous and complicated attempts to land my first internship with the UN Agencies in the hope of turning the internship into a full-time role or, at least, start building my network. I left my home country thanks to a generous scholarship offered by a philanthropic organization with the hope that if I made it to America and dedicated my life and time to working hard and making the world better for all people, I would inevitably succeed. And, if in the process, I could find career growth, financial gain, and perhaps most importantly, happiness, agency, and freedom, I would have made it in life. In reality, however, things turned out very differently: having left Turkmenistan to escape limitations, I found myself facing an entirely new set of challenges.

COMING TO AMERICA

In a traditional nomadic style of Turkmens, my mother stuffed two large suitcases with nonperishable food, medicine, and clothes so I would not spend money in the United States. I took a mental picture of my family at the airport, as I knew I wouldn’t see them for a long time until I claimed my share of bread and butter, liberty, and a career in the “paradise” for dreamers: America. After the tears and goodbyes, after flights and connecting flights, after the wide-awake hours of overexcitement in the dark aircraft, I landed in New York City, a place I had loved long before stepping onto its soil.

Image courtesy of Guzel Tuhbatullina, used with permission.

Image courtesy of Guzel Tuhbatullina, used with permission.

Despite the heavy heat and humidity, I could not believe that I was in NYC. I was stumbling through the crowded streets filled with skyscrapers, speedy walkers rushing to work, bright lights, yellow cabs, and busy traffic, smiling from ear to ear. As I strolled through the city, I found myself in front of the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Midtown Manhattan. This was the very same hotel where Akeem’s mother, father, and entourage stayed when they arrived in NYC. Even though the flag of Zamunda was missing, it was impossible not to recognize this jaw-dropping building from my favorite childhood movie. I was engulfed by a tornado of emotions. My heart was beating so fast that it felt like I had a hummingbird in my chest, and tears rolled uncontrollably down my cheeks. At that moment, I felt like I was in a circle of privilege and gratitude.

There was a part of me that sensed the road that lay ahead would be tough. I knew that I had to get excellent grades even to have a chance to withstand the fierce competition to land an internship with the UN — a necessary foreground for career development and networking. As a young and ambitious girl from Turkmenistan, I naively believed I could be a change-maker working with or alongside the UN, and that I could create better prospects for my people. Soon I would learn that neither good grades nor an inextinguishable desire to fight injustices was enough to land a meaningful, paid job, complete with a work visa.

RHETORIC VS. POLICY

The spread of the ideal of women’s empowerment in the post-Soviet space influenced my thinking in unprecedented ways during my childhood in Turkmenistan. Despite growing up in a patriarchal society where I was expected to be married by the end of high school, aid programs that supported developing nations and countries in transition gave me the freedom to dream that besides marriage, motherhood, and caregiving, I could choose a different path leading to a world-class education.

Carving out an authentic path and integrating into a new culture while trying to stay true to the culture of my community is a difficult journey, as any dreamer will tell you. I worked hard to ensure I was receptive to new experiences and contradicting schools of thought, and remained open to change, growth, and redirection. My path to realizing my American Dream included pushing boundaries, advocating for myself, becoming the voice for my community, and discovering new ways of relating to others.

While completing my studies in the United States, I felt as if my escape from Turkmenistan in search of education, and my identity as a feminist were coming full circle when I read Malala Yousafzai’s memoir. Inspired by the achievements of this Pakistani young activist and 2014 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, and her activism in the UN, I began to believe that I too could become an agent of radical change by working in the development sector. But in my attempts to obtain an internship with the UN or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), I felt betrayed by those very same institutions.

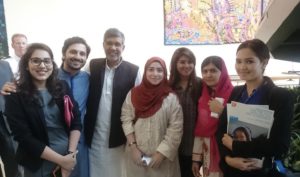

Jahan Taganova with Malala Yousafzai, Kailash Satyarthi, and youth activists at the UN, 2015.

Jahan Taganova with Malala Yousafzai, Kailash Satyarthi, and youth activists at the UN, 2015.

The institutions that advocate for women’s and girls’ empowerment are the very same institutions that have unpaid internships, expect individuals to be well enough off to work for free, and do not sponsor international professionals for work visas. I was entering a world that was advocating for women’s rights from afar, but when real, intelligent women came knocking on their door for a chance to rise and change the world, they were hardly given a chance.

THE AMERICAN DREAM

Unpaid internships at the UN and in the majority of nonprofits in expensive cities like NYC effectively turn off international students from developing and underdeveloped countries. Only the most privileged young people have the resources to accept unpaid internships, which makes equity nearly impossible.

If international students who come from low-income households agree to an unpaid internship, they soon find themselves living in tents outside the UN headquarters or traveling a two-hour-long physically grueling commute, surviving on rice, $1 pizza slices, canned goods, and instant ramen. For students who were not born into privilege, doing an unpaid internship means barely scraping by.

The concentration of power and opportunity among those already privileged narrows the talent pipeline and reinforces exclusivity over diversity.

I could not afford to live in the United States on the “salary” of an unpaid internship; that was a fact. So, after graduation, I began to seek full-time work or paid internships. With only over 800 Turkmenistani students studying in the United States, there is a dearth of micro-community role models I could rely on for guidance and coaching. Generally, Turkmenistani immigrants settle for low-paid, low-skilled work because they lack friends and family who can introduce them to the world of professionals working in white-collar jobs. It is difficult to carve a place in a city of millions, especially if you are an international student and don’t know the ropes. Sometimes, it felt that all doors of the development sector were closed to someone like me, regardless of my qualifications or ability to complete the work.

Connections and money count more than talent in America’s current system, which leads to a labor market economy where the most well-connected people are given the most opportunities and access. Networks remain the critical currency of getting ahead in the US labor market, where an estimated half of jobs are obtained through networks, as Mark Granovetter, author of “Getting a Job: A Study of Contracts and Careers,” wrote. Through my experience, I too learned that the gateway to the development sector organizations is not equally open for international students, who lack networks in the United States.

The lack of financial resources also restricts our ability to network with colleagues in informal settings, such as after-work drinks, which is often the way to build career relationships. Networks can be transformative door-openers for everyone, and underrepresented professionals, especially from Global South, who lack influential connections, could benefit immensely from having access to influential ties. For people from marginalized backgrounds, it can be difficult to access such networks, because people in positions of power and privilege often “gatekeep” access to their inner circles. I, for instance, was never able to meet with some senior diplomats over a cup of coffee, despite my efforts.

Diplomats may have busy schedules, but I think they’re also missing the opportunity to interact and learn about underrepresented countries first-hand. The experience made me wonder if those in power are concerned about country-scale change and truly invested in bringing the voices of women from the Global South to the forefront of sustainable development. The concentration of power and opportunity among those already privileged narrows the talent pipeline and reinforces exclusivity over diversity.

WHO RUNS THE UN?

The UN, which exists to protect human rights, fight inequality, empower the marginalized, and champion social justice is failing to practice what it preaches. Instead, it promotes labor practices that discriminate heavily against the poor. Even the lowest salary at the UN exceeds the budget allocated for youth engagement. As a leading institution in charge of global governance, the UN should represent people from all around the world, but the internship programs at the UN lack diversity. For instance, 87% of respondents to the Fair Internship Initiative’s 2017 Global UN Internship Report came from upper-middle or high-income countries.

The same institutions that advocate for women’s and girls’ empowerment are also the very same institutions that have unpaid internships, expect individuals to be well enough off to work for free, and do not sponsor international professionals for work visas.

In 2014, I was fortunate that my resume and cover letter landed with Sofia Garcia-Garcia, who was then leading SOS Children Villages’ (SOS CV) advocacy projects to influence the Post-2015 Development Agenda — a process from 2012 to 2015 led by the UN to define the future global development framework that would succeed the Millennium Development Goals. As an immigrant herself, Sofia had to navigate her way into the development sector through unpaid internships. Her personal experiences of systemic oppression shaped Sofia into a strong advocate for children’s and youth’s rights. So, she advocated for paid internships within her organization and devised comprehensive organizational changes. I became the first paid intern at SOS CV International. This opportunity was made possible thanks to a kindhearted and caring individual committed to social justice despite a broken system. There are exceptional professionals both within the nonprofit and development sectors dedicated to establishing inclusive and equitable policies that will allow young professionals from the Global South to succeed, but it shouldn’t be left to luck and individual actions alone, there must be systemic change.

Interning as a Lobbying and Advocacy Trainee at SOS CV International, I often worked in the UN headquarters on the post-2015 Development Agenda and provided inputs to the text of the Agenda 2030 alongside other nonprofit professionals. However, I was struck by the absence of professionals from the Global South where most of the development aid was directed. In fact, as of September 2022, Central Asian nationals are less than adequately represented in positions that are subject to geographical distribution at the UN. The UN has been working hard in recent years to better represent nationals from underrepresented Central Asian countries by including them on the priority list of the Junior Professional Program (JPO). Among 335 JPOs selected between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2013, only 13 came from Developing Country Candidate Nationalities (DCCN), which included a minority of candidates from Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Young, intelligent, hungry, and sophisticated candidates from Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan are practically invisible.

I had naively believed that the direct involvement of a stakeholder from the community in decision-making would be routine at the UN, but that was not the case. To put it more bluntly, the development sector (and the nonprofit sector as well) are strikingly white, saturated by self-proclaimed “specialists” and “experts” on Central Asia, and lack an actual presence from Central Asia. As such, the projects designed and implemented by these international “experts” are often detached from historical and contemporary contexts, have little to no practical value for the public, or fail to give adequate analysis to power structures and policy levers that white “experts” champion as proposed “solutions” maintain the status quo by promoting incrementalism without addressing root inequities. This results from working on these issues rather than working with the community.

When young professionals like myself, who have been born in developing countries, ask for work permit sponsorship or a diplomatic visa because our right to remain in the US is tied to it, we are judged through the deficiency lens: we are not educated enough, our accents are used to diminish us, our lived experiences in the developed world are discounted as biased. As international students from developing countries, we are often left behind in figuring out our legal status. The result? The people the development sector is working to “help” are shunned from opportunity, time and time again.

To implement projects and achieve larger systemic change in a context-sensitive manner, we need experts who can both speak the language of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and understand the local cultures, history, and politics, and can serve as bridge-builders. Therefore, to devise social impact and solve the world’s entrenched problems, the development organizations must revise their internal hiring and Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIB) policies to reflect a foundational and transformational intention to attract and support international students and immigrants that have a more bottom-up and real-life knowledge of the communities these organizations aim to aid. Ultimately, no matter how hard immigrants work and study, if the issues pertaining to opportunity, accessibility, and DEIB are left unresolved and unacknowledged, unequal power relationships will impede our ability to make the American dream a reality, prevent changing attitudes about immigration, and make the development sector more representative of communities they serve.

THE ACTIVISM OF ACCOUNTABILITY

My testimony might give off the impression that I am complaining and being unthankful for the opportunities that NGOs, foundations, and the US have provided to me. However, as Sarah Ahmed — a prolific feminist scholar, writer, and activist — explains, identifying problems in the structure of impactful organizations isn’t complaining. It’s a form of activism that holds organizations accountable for their unjust and discriminatory practices. Complaints make shared problems of international students in the United States and young professionals from the Global South visible, audible, and readable. It is practical activism that aims to make our world fairer and focuses on long-term systemic change. We channel our outrage into finding solutions by connecting the dots between governments and immigrants, organizations, and international talents. Listening to professionals from the Global South, learning from our lived experiences, and taking intentional actions to implement equitable practices that hold organizations accountable for their unjust hiring practices will help talents to thrive, generate fresh thinking, and innovate helping organizations to succeed in their mission.

This type of activism is a form of diversity work and part of the process of rebalancing existing power imbalances and leveling the playing field for all minorities in the development and nonprofit sectors. For any individual, especially women from the Global South, who have been told that injustices you observe are “complaints,” I challenge you to respond with this answer: “Asserting agency and pushing back against disempowerment isn’t complaining. It’s a spark to wider systemic change.”

And as a message for all of my dreamers from Central Asia, who imagine the day they too could touch down in the United States to seek a new beginning with boundless potential, realize their American Dream, and find liberation: freedom might smell like McDowall’s, and the United States might be as tempting as a juicy burger, but the road to liberation is costly. Are you ready to swallow the realities: the constant struggle for your work permit, landing a decent job, being othered, and trying to belong? Are you determined enough to unravel authentic America with its racism, generational struggles, and traumas that you will have to endure before its opportunities come knocking at your door?

The America we know from Hollywood movies and through foreign aid programs is an image of a country that is loving toward immigrants, a democratic government that lives up to the belief that all people are equal, and endowed with unalienable rights including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But as with everything, there is a shadow side to this American Dream.

There are immense struggles with immigration, hidden hate, internalized oppression, and silencing, which can forever alter your relationship with this country. Will “freedom” and the American Dream still be enticing despite low-grade fear about our second-class status? Are you ready to work non-stop to make your dreams come true no matter the odds, no matter the discrimination you will endure, and no matter how many glass ceilings you will have to break? And most importantly, are you ready to grow a thick skin to withstand othering, stigma, racism, rejection, and discrimination?

It is inevitable to experience the dark side of the American Dream but know that there are still compassionate, affectionate, and understanding individuals willing to lend a helping hand, and that opportunities still exist in the land of the free for the brave dreamers. In fact, this land needs immigrants like us to be the next in the legacy to fight injustices and dogmas, and do our part in rebuilding the system in an equitable and just way, so that we do not fail the next generation of dreamers in the paradise-for-strivers called America!

A native of Turkmenistan, Jahan Taganova is One Young World Peace Ambassador, water diplomat, Central Asia’s civil society representative, scholar, writer, and nonprofit professional based in the United States. Jahan is a fearless advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Rooted in her Central Asian origins, in her writing on DEI, Jahan explores the challenges and opportunities immigrants and minorities face when in their host communities. Her research interests lie at the intersection of water governance, integrated water resources management, sustainable development, climate change, and social justice. She is also on LinkedIn.