On Feb. 6, Chile’s right-wing former president Sebastián Piñera died of asphyxiation as a result of submersion, after a helicopter he was piloting crashed into a lake at Lago Ranco in the Los Rios region. A few days later, his funeral, held in the capital city Santiago, carried a message on behalf of the Church, asking Chileans “to work together and unify in memory of the former president.”

But Chile’s Communist Party, as well as human rights and memory organizations in Chile, have voiced contention over Chilean President Gabriel Boric’s statement on Piñera’s death. Boric, who was elected president of the University of Chile Student Federation (FECh) in 2011 and was one of the main spokespersons during the student protests between 2011 and 2013, which became known as the Chilean Winter, struck a tone rights organizations described as denialism.

Boric was particularly criticized for stating that during Piñera’s presidency, “the complaints and recriminations were, at times, beyond what was fair and reasonable.”

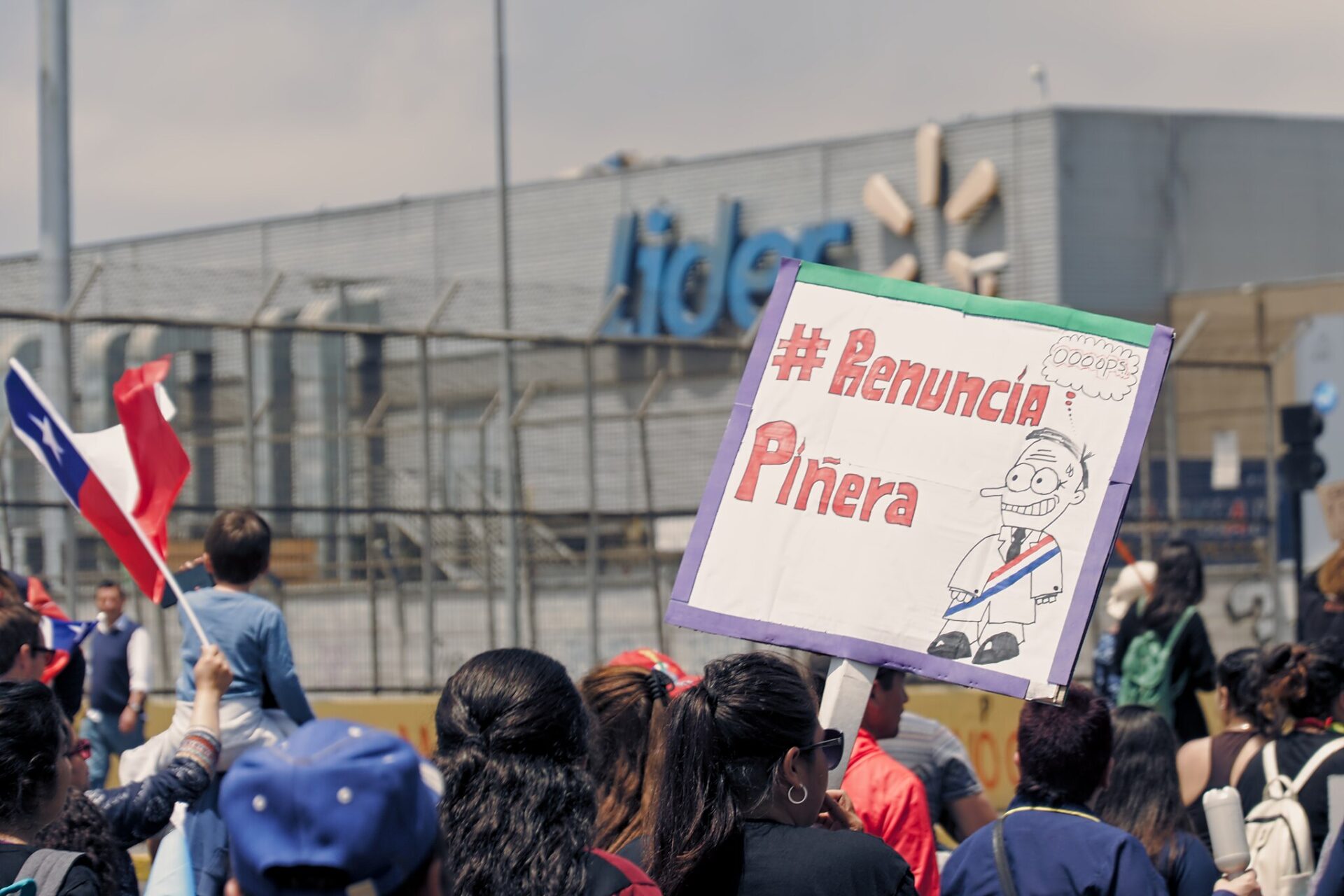

The Group of Relatives for the Disappeared Detainees (AFDD) and Londres 38 expressed their condolences while warning against forgetting the human rights violations committed by Pinera’s government, notably the repression of the 2019 protests during which the president authorized military curfews and the military were accused of various human rights violations, including torture, disappearances, and intentionally shooting protestors in the eye.

Members of the Chilean Communist Party Lorena Pizarro and Carmen Hertz rejected Boric’s statement. “What was ‘beyond what was fair and reasonable’ were the murders and mutilations during Sebastián Piñera’s mandate,” Pizarro stated, referring to the late politician’s second term in office. Backing up Pizarro’s statement, Hertz noted that Piñera was “the institutional political person responsible for the serious and widespread violations of fundamental rights during the popular revolt.”

Neoliberalism and Repression

Liberal Party deputy Vlado Mirosevic, also former president of the Chamber of Deputies of Chile, took issue with Pizarro and Hertz’s comments, stating that Boric is committed to human rights and therefore cannot be described as promoting denialism. “The president has the duty to govern for the great majority, not for the Communist Party,” Mirosevic countered.

“What was ‘beyond what was fair and reasonable’ were the murders and mutilations during Sebastián Piñera’s mandate.”

Lorena Pizarro

Calling Piñera “a democrat from the first hour,” Boric highlighted three instances of Piñera’s leadership: the reconstruction of Chile after the Feb. 27, 2010 earthquake, the rescue of the 33 miners from the San Jose copper mine north of Copiapo in the same year, and the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The other side of Piñera’s legacy — notably the 2011-2013 student protests, and the 2019-2022 Estallido Social protests — is largely connected to the neoliberal politics implemented during the US-backed dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet between 1973 and 1990.

Neoliberalism and the ensuing repression to ensure the economic model’s survival remained unchallenged by governments across the political spectrum since the democratic transition, notably through the anti-terror legislation which center-left and right-wing presidents used to repress the Mapuche Indigenous people. Piñera created the ultimate reconstruction of the dictatorship era in 2019, and it is in this context that Boric’s statements have been perceived as denialism in a society that is still dealing with its dictatorship trauma, and in which socio-economic inequality thrives.

Wealth and Politics under the Pinochet Dictatorship

Piñera’s closeness to the Pinochet dictatorship through association started with his brother José Piñera Echenique, one of the Chicago Boys who studied under Milton Friedman and who later served as Minister of Labor and Social Welfare and Mining.

Prior to entering politics, Piñera studied economics in Harvard University, obtaining a Masters and PhD with a thesis on the economics of education in developing countries. He taught economics in several universities across Chile and also worked as a consultant for the Inter-American Development Bank between 1974 and 1976, and for the World Bank between 1975 and 1978. Both banks gave financial support to the Pinochet dictatorship.

Piñera also assumed several positions in the financial private sector and in 1979 created Bancard S.A., which saw the introduction of credit cards in the country. In 1982, an arrest warrant was issued for Piñera for failing to transfer over $38 million from Banco De Talca, where he was general manager, to Chile’s Central Bank. His acquittal was facilitated by Monica Madariaga, who at the time served as justice minister during the dictatorship.

Piñera’s first foray into politics was stating that he voted against Pinochet remaining in power in the 1988 plebiscite. The following year, however, he was campaign manager for Hernan Buchi, who had served as finance minister during the dictatorship. Piñera also launched his campaign for the parliamentary elections in the same year as an independent candidate under Renovacion Nacional (RN), and got elected.

In 1998, when an international warrant issued by Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzon led to Pinochet’s arrest, Piñera publicly defended Pinochet as RN senator, declaring the warrant an attack on Chile’s sovereignty and appealing for consideration of the dictator’s alleged fragile health.

Piñera lost the presidential elections to Michelle Bachelet in 2005. In March 2010, he assumed office as the first right-wing democratically elected president since the dictatorship, having defeated Eduardo Frei Ruiz Tagla. He served another presidential term from 2018 until 2022.

Presidencies, Violence, and Protests

Chile was catapulted to world attention when 33 miners were trapped 700 meters (around 2,296 feet) underground as a result of a cave-in at the San Jose Copiapo copper mine, and rescued after 69 days. For Piñera, the rescue was an opportunity to regain positive traction after facing severe criticism at the handling of the tsunami aftermath in February 2010.

The mining industry in Chile has been linked to neoliberal policies dating back to Pinochet, and Piñera was no stranger to corruption either. In 2021, the Pandora Papers investigation linked Piñera to the 2010 sale of the Dominga mine in the Coquimbo region, in which his children owned a share of 33.3%, to his friend and businessman Carlo Delano, for $152 million, through an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands. The sale included a clause that prevented the owner from “establishing an area of environmental protection in the area of operations of the mining company, as demanded by environmental groups.”