Two years ago, the world came close to ending the hamburger wars. Burger King, of Whopper fame, offered a truce to rival McDonalds’ Big Mac by suggesting that the fast food giants create a McWhopper to celebrate and raise funds for the International Day of Peace, September 21. A clever ad campaign showed a pop-up restaurant to be erected in Atlanta, Georgia, with workers using specially-branded uniforms, as a statement that peace, at last, had been reached in the burger wars. Burger King even joined forces with non-governmental organization Peace One Day to support the United Nations’ mission of embracing a world without war, agreeing to donate the profits from this pop-up to peacebuilding.

But as with any difficult negotiation, McDonald’s literally didn’t bite. Its management called it a public relations ploy by Burger King to encroach on McDonald’s market share. So much for waging peace, even on a day dedicated to observing it.

This year’s theme for the United Nations International Day of Peace is “Together.” It will focus on the plight of refugees and the displaced peoples around the world. It offers yet another opportunity to illustrate how the kitchen can become a new venue of foreign policy. With more than 60 million people living in limbo, forced to flee their homelands due to conflict, it may also be a time to reconsider whether food can be a bridge to building a more peaceful and stable environment for those who have suffered in recent wars.

UN Secretary General Antonio Gutieres stated that “we must resist cynical efforts to divide communities and portray neighbors as ‘the other.’ Discrimination diminishes us all. It prevents people — and societies — from achieving their full potential.” He added, “Together, let us build bridges. Together, let us transform fear into hope.”

Without the Madison Avenue hype, refugees using food to help them earn a livelihood has gained increased attention as an important way to build understanding. Isn’t it true that we first learn about other cultures through our palates? Think ‘Kimchi Diplomacy’ or Korean Tacos. Don’t we react to another culture positively or negatively by the taste of a particular food we are served?

The potential to reduce discrimination, while also creating sustainable livelihoods, can happen through the kitchen. Refugee chefs are using their culinary skills not only to feed their communities, but to offer a taste of their homelands to others by driving food trucks, selling at farmer’s market stalls, and joining festivals where different cuisines are featured. They are also opening restaurants that feature their respective cuisines.

In France this summer, two French businessmen expanded a food festival experiment, Food Sweet Food, from a small one-time fair to a multi-city effort in France to present the foods of newcomers. The project’s success offers hope of creating similar types of movements in other countries.

A London based Somali refugee, Chef Ahmed Jawa, recently returned to his home in Mogadishu, a city recovering from decades of conflict, to open a chain of restaurants, The Village. His investment sends a signal that a more stable environment could allow others to follow. For local residents, the restaurants create some form of normalcy amidst a war-torn environment.

Syria’s refugees who continue to flee the ongoing brutal civil war are also using their foods to build new businesses and new lives. Turkey has been an epicenter of this activity, with restaurants, bakeries, and other food-related activities helping to earn a living while also providing a taste of home. A new program, Livelihoods Innovation through Food Entrepreneurship (LIFE), will help Syrians living in Turkey to develop culinary workers and sustainable businesses by training and investment in food incubators.

In Canada, a country that has welcomed Syrian refugees, there has been a focus on women in projects like Newcomer Kitchen. Co-founder Cara Benjamin-Pace said “we want to celebrate that they hold the knowledge of the oldest cuisines in the world. Our goal is not to train these women into line workers in the food industry. Our goal is to bring together and celebrate them as women and in the community.”

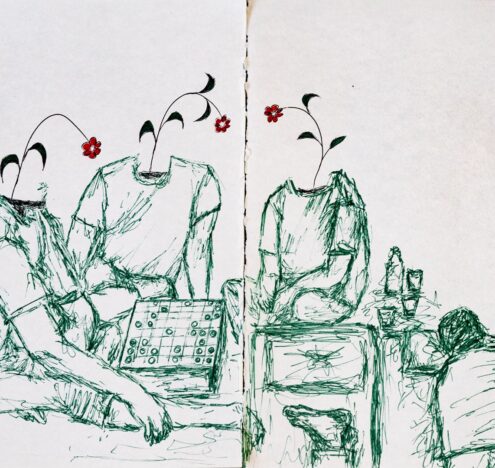

All of these efforts to unite refugees through their cuisines may be more consistent with the concept of “Together” than any attempt to commercialize the pursuit of global peace. Commensality, or coming together around the table, is an ancient practice documented from biblical times. It may offer a better way to engage those who have been forced to flee with those who are looking for ways to make our planet a less divisive and hateful world of conflicts and wars.

Almost two decades ago journalist Thomas Friedman posited the Golden Arches Theory of conflict prevention. The theory points out that no two countries that both have McDonald’s franchises have ever gone to war. The reasoning behind this correlation, Friedman suggested, is that once economies become sufficiently integrated, both the cost of going to war and the amount of contact between two countries will increase. Both of these factors lead to more effective conflict resolution, as states will attempt to pursue the more economically beneficial option. While the Russian invasion of the Crimea has dispelled this thesis, we should not discount the importance of eating together as a means of resolving differences, especially for those newly arrived refugees.

In 2017, we should consider the prospect of peace being built not through the normal channels of multilateral diplomacy of the United Nations, but around the platters of shawarma and hummus that are offered to neighbors, and at the counters of myriad restaurants that now are commonplace in the landscape of eateries around the globe. We may not need a McWhopper, but we continue to need our kitchens to help forge a new paradigm of global peace.