“The Long Tunnel” is a series of articles reflecting on the impact of Sept. 11 and how it has shaped the world we live in today. You can read more in the series here.

My family once watched the fireworks every Fourth of July. We lived in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, and drove every year to watch the fireworks display in the park behind the local high school.

But one summer, as we were looking for a parking spot, someone threw a rock at our van.

“Go back to your country!” someone shouted.

“Go back to Iraq!” shouted another.

At that moment, I could have asked several, important questions, like: Who were they? What gave them the right to throw rocks at us? Had we sat beside them to watch fireworks the year before?

Instead, I remember wondering: How did they know we were Arab?

I’ve thought a long time about why that question stuck with me, why it was the first thing I asked as my father drove us home. All my life, I’d been misidentified as Mexican, Brazilian, or Greek — never as Arab. In lines at the grocery store, my mom would always get asked “where are you from?”. They never guessed we were Syrian, and half the time when we told them, they didn’t know where Syria was.

But as the sun set that night on the 4th of July, a group of people managed to see us through our closed window and identify us as Arab, and they reacted with a physical violence I’d never experienced before.

Twenty years after 9/11, I think I know why that question was the first that came to my mind. I think, despite being a child, I recognized that how we were treated as Arabs in America had changed — and not for the better. Seemingly overnight, we’d gone from being exotic to being a threat, from being perpetual foreigners with sensual traditions to being wholly unamerican with barbaric and antiquated traditions.

I know no Arabs who didn’t feel a seismic shift in how we moved in this country after 9/11. For that reason, the slogan #neverforget has always left a bad taste in my mouth, because if you grew up Arab American after 9/11, you were never allowed the privilege of forgetting.

You were reminded every time you were told by your parents not to speak Arabic in public. You were reminded every time you were searched in the airport, or pulled aside by police officers. You were reminded every time you turned on the news and were bombarded by news of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and of Guantanamo Bay. You were reminded every time your friend joked the FBI was recording your get-togethers, and every time a classmate would call you a terrorist.

Arab-Americans don’t need coverage of 9/11’s twentieth anniversary to remember the day — we just need to turn on the news or go to the airport.

Arab-Americans don’t need coverage of 9/11’s twentieth anniversary to remember the day — we just need to turn on the news or go to the airport.

Growing up, the racism we experienced was often isolating. It wasn’t taught in schools and rarely discussed in the media. Unless you grew up in a community with many Arabs, you had few friends to exchange stories with. We couldn’t watch characters on TV experience racism and discuss it — on the contrary, the TV was often where the racist depictions of Arabs were most prominent.

Twenty years after 9/11, sometimes the anti-Arab, and more broadly, the anti-Muslim racism can feel just as vitriolic and intense as it was when I was growing up. Despite the hard work of people like Jack Shaheen, Evelyn Alsultany, and Sue Obeidi, and the dedication of groups like the Arab American Institute, and the growing presence of shows like “Ramy” on air, Arabs and continue to be one of the most misrepresented and underrepresented groups in the media.

However, whenever I feel like the issue of anti-Arab racism seems too big, I go backward in time and realize that, despite feeling as a child that we’d experienced a seismic shift after 9/11, Arab racism in America isn’t new.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Arabs often went to courts to justify their right to be citizens, and lobbied against immigration quotas targeting Arab immigration. Syrian store owners were sometimes threatened and had their stores burned down by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1927, there was a long-running exchange in the periodical “The Syrian World” after a Syrian doctor in Oklahoma argued that because of racism, all Syrians should return to Syria. Dr. Shadid described being alienated by KKK members in his community, and discussed his frustrations with watching his kids be bullied despite having been born in America.

“I would rather live on equality with any people than to live on a basis of inequality anywhere in the wide world,” Dr. Shadid writes in an article. “I want to live in a country where I can look any man in the face as a sovereign citizen; where I would not need to be ashamed of my nativity, my ancestry, my racial traditions, etc. Where else in the world can a Syrian so live, except in Syria?”

In the weeks that followed, numerous writers and readers weighed in on the issue: could Syrians truly thrive in the United States? While some agreed with Dr. Shadid, sharing their own experiences with racism, for most the answer was a resounding yes.

“America has been too benevolent for us to permit one or two hundred bigoted so-called Americans to cause us to lose faith in our adopted country,” argues one writer, who signs their response to Dr. Shadid with only the initials “E.K.S.” Like others like them, E.K.S. argues the answer isn’t emigration or assimilation, but showing Americans why they should value their Arab neighbors.

“Why bake pies if we can excel in kibbe?” E.K.S. asked.

The racism we face today might look different from the racism our predecessors faced in the 1920s; however, its systemic practice remains the same. A minority of bigoted Americans supported by a government that doesn’t hold them accountable for their bigotry, and instead caters to it, and a media eco-system that plays to extremes to entertain audiences.

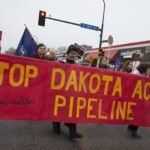

In other words, while the Arab racism we experienced after 9/11 might feel unprecedented to us, we aren’t the first Arabs who’ve confronted American racism. If we take the time, we might not only draw comfort from them, but learn from them. Just as they went to court to lobby against unfair immigration quotas, we can lobby for bills like the #NoBanAct to ensure that if America ever experiences another tragedy, there are safeguards to protect American communities. Just as they cultivated speakers and writers to educate the American public about Arabs and the Arab world, we can support our writers, artists, and filmmakers who are trying to share our stories.

Twenty years after 9/11 doesn’t just mark twenty years since the unjust deaths of thousands of Americans, it marks twenty years of racist and retaliatory policies at home and abroad. But like so many racist policies in America’s past, we can unmake them, and work towards an anniversary of 9/11 which both honors the dead and makes sure that the violence which followed isn’t repeated.

Zaina Ujayli is a current PhD candidate in American Studies & Ethnicity at USC where she studies Arab diaspora in the Americas, as well as Arab representation in American politics and film.