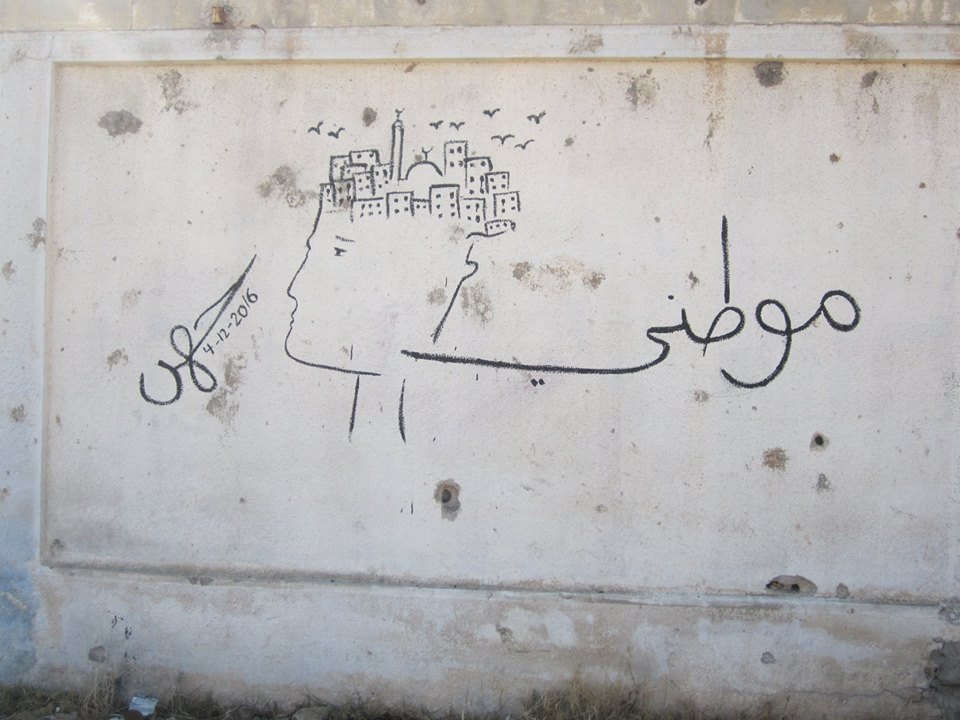

On Feb. 16, 2011, a 14-year-old boy and his friends pulled a prank in their hometown of Daraa in southern Syria. They scrawled the walls of their schoolyard with spray paint: “The people want the fall of the regime” and “Your turn is coming, doctor,” in reference to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

The words started a war.

Syrian security forces made an example of the children, detaining and torturing them for more than a month. In the wake of their release, what began as a local protest movement morphed into an international conflict that still rages today, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. Their words were the first, but certainly not the last, protest painted on the walls of Syria’s civil war.

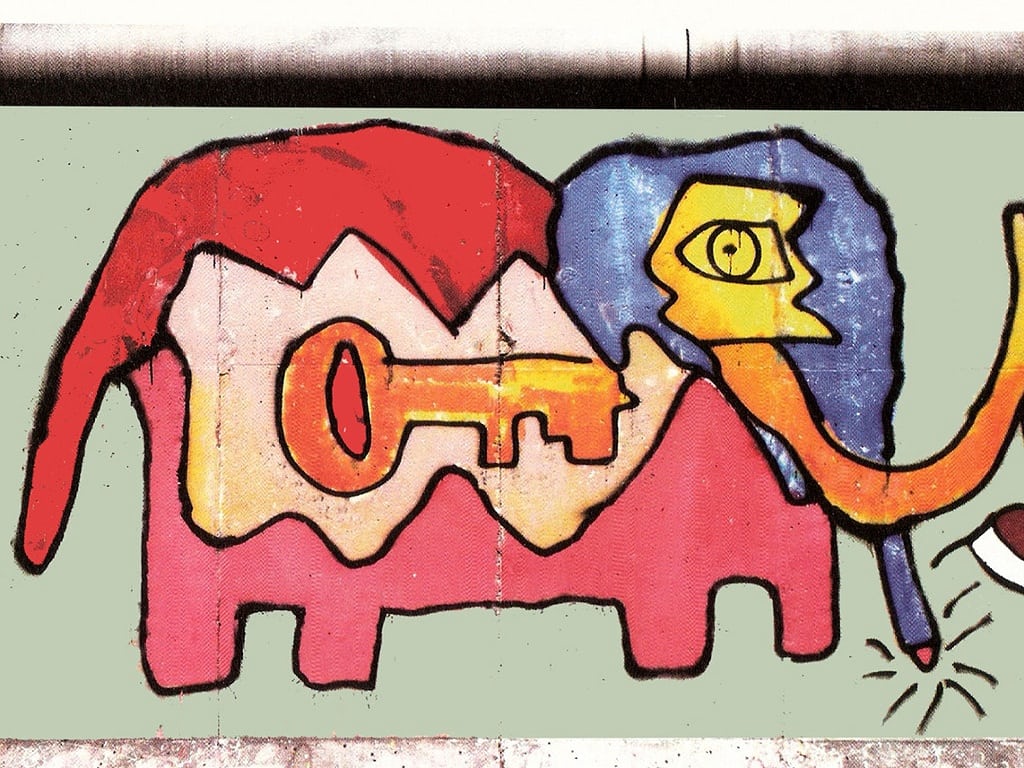

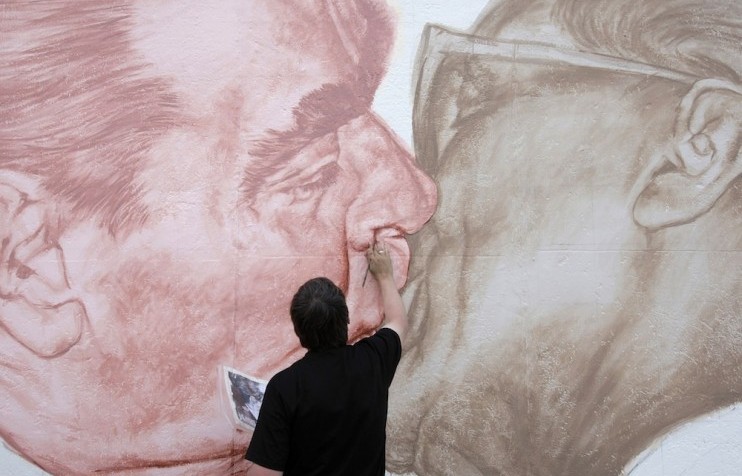

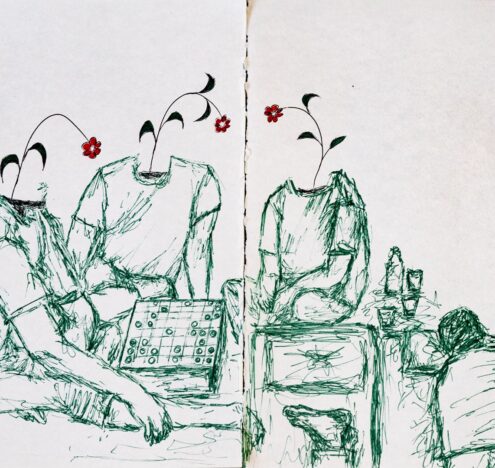

Over decades and even centuries of conflict, political art has become part of the landscape of war. Graffiti is, by definition, an act of defiance, and as political art, it’s especially suited to battle. Graffiti goes up quickly and leaves a bold mark, even after authorities destroy the evidence.

Where they don’t, the art remains — a proud and painful reminder of a shared history of violence and strength.

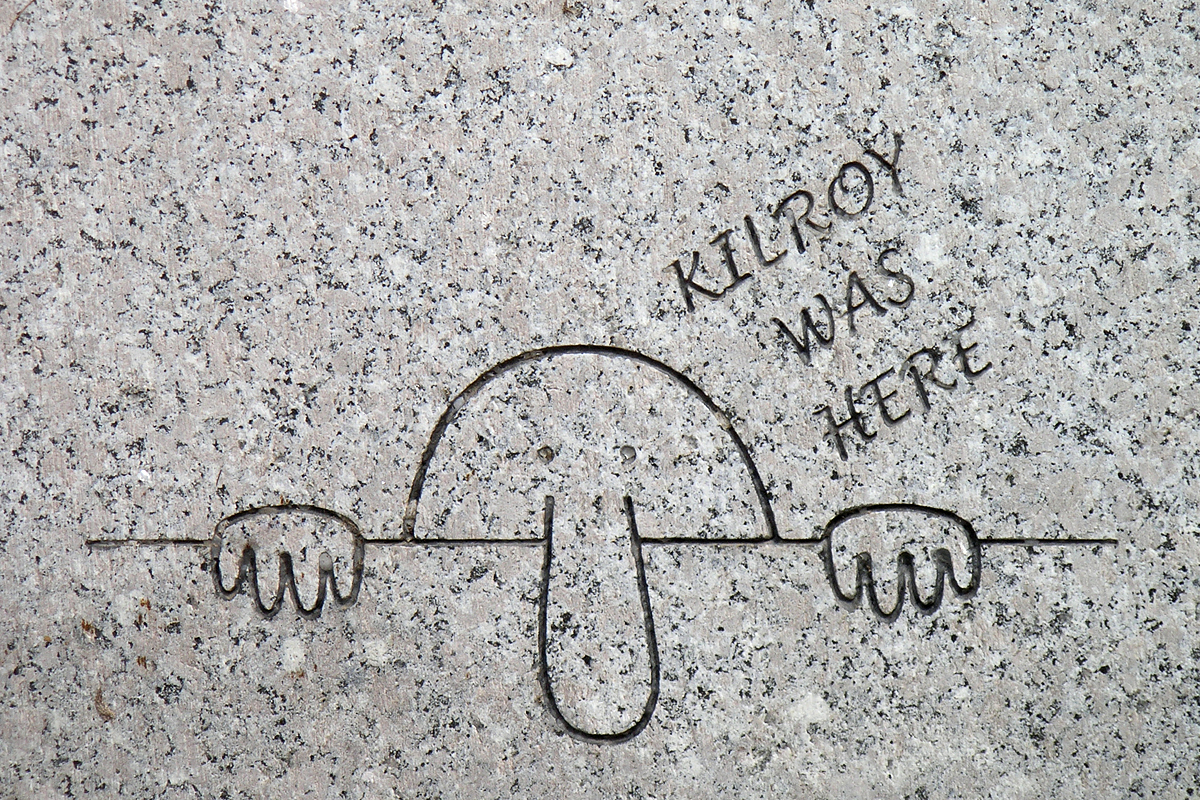

Our history of writing on walls in times of war is long and storied. WWI graffiti in France shows soldiers “wanted to be remembered.” US Civil War graffiti shows the same. Today’s protests range from simple but powerful phrases of resistance to intricate exhibitions spread across multiple buildings.

What follows is just a sampling of the powerful art of resistance in times of war: