July 26 marked the 71st anniversary of the attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba in 1953. The incident was the first visible inkling that revolutionary struggle against the US-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista had started in Cuba. Commemorating the occasion, the World Federation of Trade Unions issued a statement calling for solidarity with the Cuban people, calling for an end to the US illegal blockade, the return of occupied Guantanamo to Cuba, an end to terror attacks and foreign intervention, as well as the removal of Cuba from the US State Sponsor of Terrorism List.

“For six decades, the heroic Cuban people have been confronted with the criminal blockade imposed by the USA and the constant attempts at foreign intervention in the country,” the statement reads, while expounding on how the US exploits Cuban dissatisfaction with economic shortages as reasons for meddling in the country.

One route the US has used to meddle is through the media. Speaking to the press about US-funded journalists in Cuba, mostly through the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), former US intelligence analyst Fultom Armstrong described the strategy thus: “We win if the opposition media gain a foothold and we win if they provoke government repressions. That thrusts the government into a dilemma — to let the organizing and funding go forward or to risk image and credibility by crushing it.”

A History of Intervention

Intervention through the media is a decades-long strategy the US has used against Cuba. In 1960, for example, the US planned for destabilization through Swan Island — using a radio channel that would also transmit coded communication to Cubans involved in subversive activities against the island. Radio Y Television Marti, proposed by US President Ronald Reagan in 1983, is perhaps the most well-known media subversion project, funded to the tune of several million dollars a year.

Intervention through the media is a decades-long strategy the US has used against Cuba.

In 1984, Reagan used the airwaves to deliver a speech to Cubans on the 25th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution, citing Cuban government censorship as the reason for setting up the radio station. “The objective of the Radio Martí program will be simple and straightforward: tell the truth about Cuba to the Cuban people. We want you to know what you haven’t been told,” Reagan declared.

Meanwhile throughout his term in office, Reagan was busy intervening in Central and South America, illustrating the compatibility of US democracy with political repression.

Shaping Moncada’s relevance today is Cuba’s history, particularly the island’s history of colonial oppression and the US refusal to let go of the country that was once its backyard for exploitation.

Beginnings of US Imperialism in Cuba

A philosopher, writer, and political activist, Jose Marti was a prominent figure in the Cuban revolt against Spanish colonial rule. Marti’s first awareness of colonial oppression happened during the Ten Years War in 1868. As a result of his writings, published a year later, Marti was imprisoned on the Isle of Pines and exiled to Spain a year later. Upon his return to Havana from exile, Marti’s writing continued promoting Cuban independence.

He was, however, cautious in implementing revolutionary struggle, noting the time was not right for immediate confrontation. In Latin America and in the US, Marti continued promoting liberation, garnering both a following and the means by which to prepare for the revolution. In May 1895, just a little over a month after the revolution started, Marti died in battle.

While the colonial struggle against the Spanish waged on, the US Congress passed resolutions declaring Cuba’s right to freedom and independence. However, the Treaty of Paris, signed between Spain and the US in 1898, would see the former relinquish Cuba. It also recognized the ongoing US occupation of the island. This reflected what US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams stated in 1823: that Cuba, “almost within sight of our shores, from a multitude of considerations, has become an object of transcendent importance to the commercial and political interests of our Union.”

Despite the Cuban efforts in fighting against Spanish colonization, the US forbade Cubans from participating in diplomatic activities. The seeds of US economic repression against Cuba were sewn: Cuban export tariffs were not cut, unlike US imports to the island, and US companies controlled most of Cuba’s exports and factories by 1902.

From Machado to Batista

The presidents who ruled Cuba until the triumph of the Cuban revolution provided the US with ample space for leveraging its interests. Under Gerardo Machado from 1925 until 1933, Cuba refrained from criticizing the Platt Amendment, which allowed the US to interfere in the island. Machado ruled Cuba for a second term after amendments to the constitution, prompting both unrest within Cuba and a purge of his opponents.

US Ambassador to Cuba Sumner Welles met with Cuban opposition groups in 1933, and the Cuban army delivered its contribution through the Sergeants’ Revolt of the same year, insisting on Machado’s immediate resignation. Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, who played a role in toppling Machado, briefly assumed the role of president until the Pentarchy coalition of 1933 — an executive commission of government that installed Ramon Grau San Martin as president and promoted Fulgencio Batista from army sergeant to colonel.

During this time, Batista was holding talks with Welles and US Ambassador Jefferson Caffrey to overthrow the government. After maintaining political control of Cuba behind the scenes of puppet governments until 1940, Batista was elected president. He served out his term until 1944, when he moved to Florida after Grau won the presidency. Succeed Grau was Carlos Prio from 1948 until 1952, which is when Batista struck again, this time by a military coup.

A year later, in 1953, Fidel Castro and the July 26 Movement launched the attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago De Cuba, altering the Cuban political landscape and beyond, as the US grappled with a revolutionary struggle that would have long-lasting influence in Cuba, Latin America, and beyond.

A Challenge to the Batista Dictatorship

Torture, in part, marked Batista’s dictatorship. The Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities (BRAC), established in 1955 with the aid of the CIA, traced its origins back to 1942. It served the same purpose of eradicating communist influence. Under Batista, a hierarchy of factions to repress was created, with the July 26 Movement and its supporters eventually becoming the top priority.

“The creation by the Cuban Government of the ‘Bureau for the Suppression of Communist Activities’ is a great step forward in the cause of Liberty,” then CIA Director Allen Dulles wrote to Batista, also emphasizing that the US would be willing to train the military in torture tactics. Preceding and mirroring the US-CIA attitude towards the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, the intelligence agency’s concern was not the torture tactics used, but how such tactics might eventually weaken Batista’s hold on the country.

“When Batista’s coup took place in 1952, I’d already formulated a plan for the future. I decided to launch a revolutionary program and organize a popular uprising,” Fidel Castro told Ignacio Ramonet. The plan, Fidel continued, was expanded in his speech “History Will Absolve Me,” which was his defense in court for being charged with leading the attack on Moncada.

Arrests and Torture

Planning for Moncada started before Batista’s coup. Fidel later recounted that the primary aim was to gather the anti-Batista forces, and 1,200 men were recruited in less than a year. Drawing a comparison with Marti, who was of Spanish origin, Fidel noted that several of the recruits were of Spanish and Galician origin. Out of the original 1,200 recruits, 120 were chosen for the Moncada assault.

The early hours of July 26 were chosen as a strategic plan by the revolutionaries, since July 25 marked carnival festival in Santiago de Cuba. However, the army patrol was not factored into the attack. As the plan fell into considerable disarray, the wrong building was captured, and the revolutionaries found themselves facing over 1,000 armed soldiers. Fidel and 19 others who survived the attack headed off to the mountains, temporarily avoiding capture.

Not everyone escaped, though. Some other revolutionaries were killed on the spot, others detained, tortured, and murdered. Abel Santamaria was tortured in front of his sister Haydee. His eyes were reportedly gouged out in her presence, apparently with the goal of coercing her into revealing the revolutionaries’ hiding place.

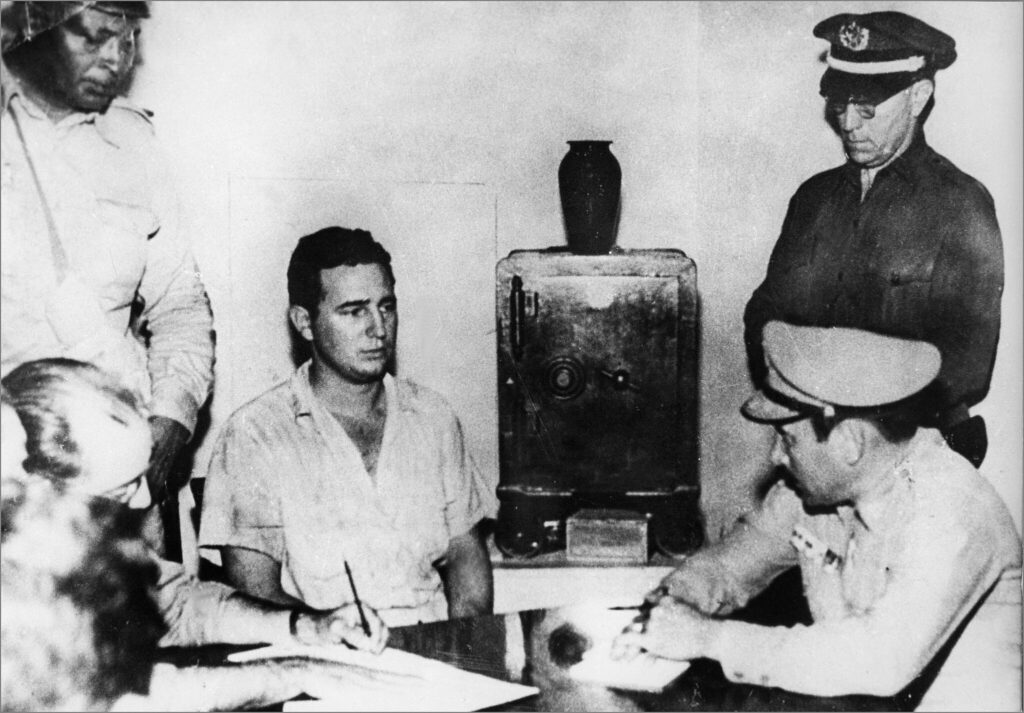

In September 1953, together with Fidel, who was captured by Batista’s soldiers in the mountains, 122 revolutionaries faced court charges for the assault. Thirty, including Fidel, were imprisoned on the Isle of Pines — the site that would effectively become an education camp for further planning the revolution.

Part of a Long Process

Moncada was part of a long revolutionary process, one Fidel said started with Marti’s revolution. As Cuba prevailed, the US persisted in its sabotage of the island through several clandestine operations, with the CIA deeply involved in attacks and assassination attempts on Fidel’s life. The illegal blockade on Cuba, which commenced under the late President John F. Kennedy, remains the most visible form of economic oppression against the island.

What Batista allowed in Cuba — poverty, lack of land ownership, lack of access to education and healthcare — the US was ready to maintain with its support for his dictatorship. It was only after the triumph of the revolution and the failed attempts to halt the revolution that the US embarked upon new ways to strike out at Cuba and Latin America through USAID.

That agency marked its decades with different aims and objectives, purportedly mirroring what revolutions sought to achieve in the region to facilitate foreign intervention. USAID claims it wants “to support partners to become self-reliant and capable of leading their own development journeys.” Many Cubans would tell you otherwise.

Moncada’s Legacy

Further back still, under the guise of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, the US attempted to retain influence over central and Latin America. Marti perceived Cuba’s independence as preventing the US from infiltrating further into the region. One former US Ambassador to Cuba during Batista’s dictatorship had even stated that before Fidel, US influence was such that “the American ambassador was the second most important man in Cuba; sometimes even more important than the president.”

Today, the US still employs various forms of interference targeted against Cuba — none of which the Biden administration or any US presidential candidates have repudiated, even rhetorically. Meanwhile, the US still occupies the Guantanamo territory. More than seven decades after the assault on Moncada, the incident remains a pivotal and significant moment in Cuban history — and it will continue to do so, so long as US oppression continues.