Books about books abound. Books about war abound. Far thinner on the ground are books about books about their roles in war. Andrew Pettegree’s “The Book at War: How Reading Shaped Conflict and Conflict Shaped Reading” is a welcome thickener. Pettegree’s book itself is substantial: weighing in at over 400 pages without notes and citations. And its bulk provides an account of the role of books — broadly conceived — during the run up to, waging of, and aftermath of the two major wars of the twentieth century.

Jill Lepore’s “The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity” argues that what at least some on one side of the conflict called “King Philips’s War” was the first media war. Lepore writes movingly of the job of words about war and wars of words: “The words used to describe war have a great deal of work to do: they must communicate war’s intensity, its traumas, fears, and glories; they must make clear who is right and who is wrong, rally support, and recruit allies; and they must document the pain of war, and in doing so, help to alleviate it. Not all words about war do all of these things, but most of them do some.”

How the medium of the book labors during war — whether through recruitment, support, documentation, or amelioration is — at the heart of Pettegree’s account. But he doesn’t end there. He also writes of the need to recruit, care for, document, and repair books themselves during times of war.

Warring Nations and Printed Materials

In Pettegree’s hands, the book is a supple category. It encompasses many kinds of printed materials. He writes: “The warring nations employed the whole panoply of print: books, pamphlets, scientific periodicals, magazines, newspapers, leaflets and broadsheet notices.” He puts that flexibility to good use by referring to changes within publishing and publishing houses; for instance, his discussion of how Penguin revolutionized the paperback in the early 1940s.

A convincing historical account needs to move in two directions at once: synchronic and diachronic. That is, it needs a description of events at a specific moment (or moments) in time and it needs to pull its narrative forward through moments in time. To tell his story Pettegree does both very well indeed.

Pettegree goes deeply into a single moment in time to paint a vivid, wide-ranging picture of the role of the book at war.

Pettegree goes deeply into a single moment in time to paint a vivid, wide-ranging picture of the role of the book at war. He breaks down how different groups of people related to books; he closely examines how scientists, spies, academics, mapmakers, government officials, troops, and authors interact with books.

By taking snapshots of a moment in time from so many different people’s vantages, he rounds out his telling of that period. In his consideration of these different groups of people, Pettegree also works to provide a rounded account of that group by considering how people in different countries — even countries at war with one another — lived out those roles.

Charting the Role of a Book in Conflict

Pettegree advances through time the story he tells about the book at war. He does so by charting the role of the book prior to conflict, the book in conflict, and the book after conflict. I often find it helpful to think in terms of a beginning, middle, and end; so while there is more nuance to Pettegree’s movement through time, it is useful to consider how he pegs his argument to the three main movements of war.

He discusses the power of books to condition a people for conflict. This conditioning can take the form of advocating for reading certain books, or the blocking, banning, and even burning of books. He investigates how and why governments work to get books into the hands of troops during the conflict and which books they are especially keen to distribute. How institutions — libraries, benevolent associations, museums and the like — at the local and national levels work to stock and preserve and conserve titles during war is also central to his account.

Again, it is important to underscore here that Pettegree’s account spans many different countries and includes countries at war with one another. Pettegree is also attentive to the fate of books in the wake of conflict as he discusses how individuals, immediate communities, and even nations reconstitute, rebuild, and reimagine their relationship to books and the institutions that support them when hostilities end.

A Theory of Meaning(s)

For all its strengths and virtues, it does seem that there is a potential layer of complexity that is missing from Pettegree’s book. A framing out — however brief — of how books shape a national identity would be very welcome indeed. His discussions of a government’s efforts to preserve its own literature or to damage the literature of a belligerent would be thickened by such an entry point. There is also, frankly, room for more critique of how governments acquired, stole, and ravaged books and other cultural artifacts in their own pasts, claimed them as their own, and then worked to hold on to, mobilize, and restore them in the face of armed conflict.

His moving descriptions of the preservation work of the British museum and library during World War II are read in a context today when we in the general population — thanks to rigorous academic theories and arguments as well as necessary public reporting — are increasingly aware of how such symbols of national knowledge and identity were built by imperial and colonial systems, the legacies of which redound to today.

Pettegree, in other words, does not advance a theory of the meaning or meanings of how the book forms, shapes, sustains, undoes, and reshapes national identities in a moment of political crisis. Elizabeth Samet’s “Looking for the Good War,” a searching assessment and reassessment of imaginative literature’s role in creating a widely-held American cultural narrative around World War II, takes that kind of meta work as its own.

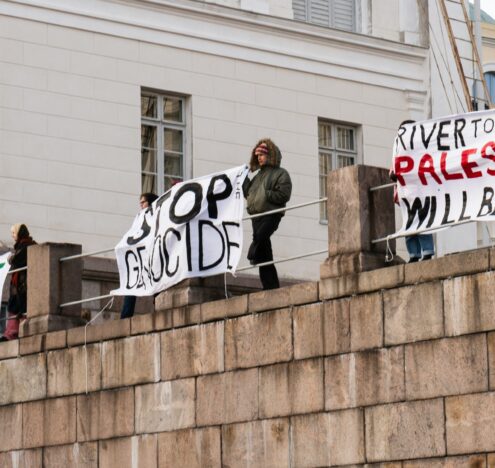

Current Conflicts

Pettegree’s book about the role of books in war emerges in a context of violent political conflict around the globe. Autogolpes within a country signal its political instability. Civil strife within borders immiserates people who live between them. And this is to say nothing of the two major wars: between Hamas and Israel, and Ukraine and Russia. The moment-by-moment, unceasing nature of writing about conflicts in real time is crucial to producing the proverbial first draft of history.

Words about these multiple, multifaceted, and infinitely complicated conflicts have a great deal of work to do — including creating meaning around the nature and stakes of the conflicts. Books provide something altogether different than the kind of immediacy that moment-by-moment news accounts can; the mediation wrought by long publishing and distribution times are aids to different kinds of reflection and understanding about the nature and stakes of a particular war and even of war itself. Across the globe, conflicts of tremendous complexity and mortally high stakes call on our capacities to make meaning of them so it feels more important than ever to understand the book at war.