The burnt orange glow of subway line 6 has always been synonymous with anticipation. Itaewon is situated smack in the middle of the line, and hipsters, youngsters, and foreigners exit the carriages in droves.

Turkish pistachio baklava greets passengers outside one subway exit. The warmth of Pakistani sour soup snakes up and down the alley to the mosque on a hilltop. On the neighborhood’s other extremity, sunny Mediterranean dishes are served amid Buddhist incense and woodwork. Below a tree-lined outcrop, Neapolitan pizzas emerge from a grotto that resembles a bohemian burrow.

On the night of Oct. 29, 2022, however, death throes engulfed Itaewon as 156 young people perished from asphyxiation in human piles. More than 130,000 people arrived in Itaewon by subway to celebrate Halloween. However, given other modes of transportation, the actual crowd might have been bigger. The tragedy took place in a sloping alleyway connecting Itaewon’s main road and its popular street lined with bars and clubs.

Given the alley’s convenience — it connects a subway exit, a large hotel, many Instagrammable spots, nightclubs, and restaurants — thousands of people were packed into the 4-yard-wide, 43-yard-long street. Even as they tripped and fell, more people barged from behind, generating a human cascade. Many of those who were trampled died instantly, while some still standing went into cardiac arrest from shoulder-to-shoulder, chest-to-chest pressure.

Itaewon’s attraction attests to its imprints of the past and present, conjuring many mixed feelings. With its smorgasbord of cuisines, immigrant populations, and party scenes, Itaewon has long been at the forefront of South Korea’s multiculturality. In the past, foreign troops and merchants sojourned here. Even though it evokes Korea’s historical weakness and foreign influence, political, military, and cultural novelties originated here. As a microcosm of the country’s early modern history, Itaewon traces Korea’s trajectory from agony to modernity and points to where the nation should head next.

ITAEWON’S ORIGIN AND HISTORY

Scholars debate the linguistic origin of Itaewon. Since the name derives from Chinese characters, three homonyms compete for original legitimacy. The simplest version posits that pear trees abounded in Itaewon in the mid-17th century, hence the name “the house of pear trees.” The second interpretation goes back slightly earlier. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a Japanese warlord who unified his country in 1590, invaded the Korean Peninsula in his expansionary zeal from 1592 to 1598. A third of the farmland lay desolate. More than a quarter million Koreans died, and countless women were raped. Defeated Japanese soldiers settled in Itaewon, leading some to claim that the name derived from Itain, “people from different places.” In a similar vein, the last interpretation alleges that Itaewon means “the circle of different placenta,” after the Korean women who bore children of Japanese soldiers after enduring various forms of atrocities.

Yet, Itaewon’s checkered history runs longer. Just as the painful memories of Japanese invasions and sexual violence gave rise to its name, its history tells of Korea’s subjugation and privation: Foreign occupiers also favored Itaewon and set up garrisons there.

Just as the painful memories of Japanese invasions and sexual violence gave rise to its name, Itaewon’s history tells of Korea’s subjugation and privation.

Throughout the 13th century, Mongols occupied the area for their war against Koreans. Later in the century, Kublai Khan, one of Genghis Khan’s successors to the Mongol Empire, established a logistical command here in his failed effort to conquer Japan. In 1637, when China’s Qing Dynasty invaded Korea, Chinese soldiers encamped in Itaewon and trafficked approximately 60,000 Koreans — 5% of the population — to China as slaves. The same year, Korea’s Chosun Dynasty capitulated and became China’s tributary state. In subsequent years, Chosun built ships offered to China near Itaewon.

In 1876, Chosun opened up Korea’s ports and started the process of modernization based on Western models. As the authorities funneled Korean rice to Japan, however, farmers and commoners struggled to secure enough rice, prompting exorbitant price surges. Meanwhile, a new elite military force adopting Japanese skills received preferential treatment, whereas soldiers of existing forces from underprivileged backgrounds received rotten and infested rice as their payment.

When the military arrested the remonstrating soldiers, hungry people from Itaewon rebelled en masse in 1882. Soon, the rebellion spread across Seoul. Temples, palaces, and Japanese establishments came under attack. In order to reassert its influence over East Asia, Qing China dispatched and garrisoned thousands of troops in Itaewon, who quelled the uprising through massacres. Having forced Chosun to ratify a trade treaty that affirmed Korea’s status as China’s client state and Chinese merchants’ privileges, the troops remained in Itaewon for another two years.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Japan replaced China as the dominant regional power. Vying for supremacy over the Korean Peninsula led to the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, resulting in a swift Japanese victory the following year. Japan ousted the Quing forces from Yongsan, the district encompassing Itaewon, and stationed their own troops there. After defeating the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Japan gained naval control around the Korean Peninsula, and Russia recognized the Japanese control of Korea.

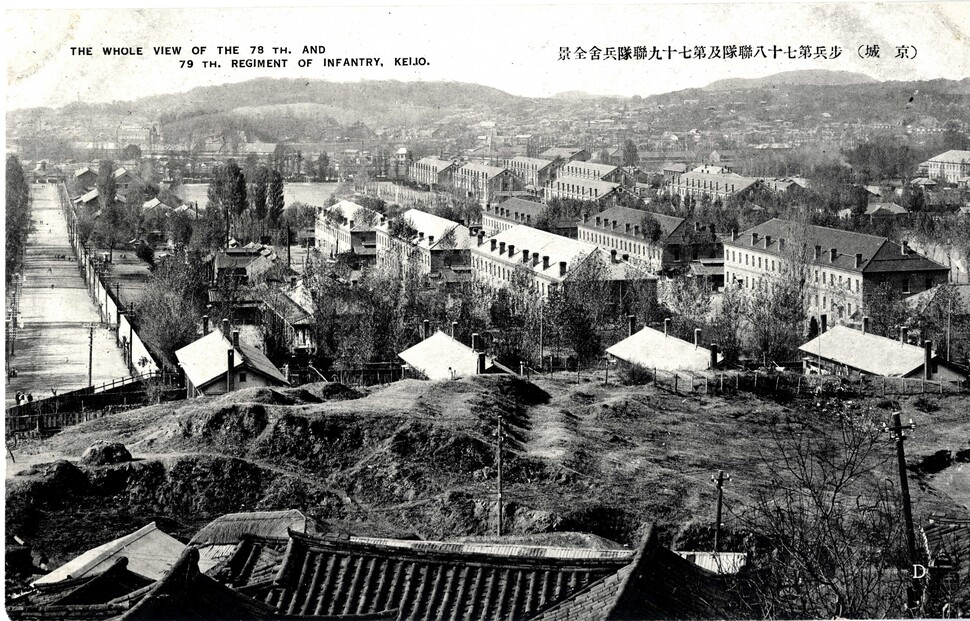

In 1908, the Japanese military installed a base next to Itaewon, allowing Japan to officially annex Korea in 1910. Itaewon’s crucial role in Imperial Japan’s global warfare continued. For example, for its invasion of China’s Manchuria in 1931, Japan dispatched soldiers quartering around Itaewon. From then on until the end of World War II, Japan conscripted and trained Koreans in Itaewon and sent them to death throughout China and the Pacific.

Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the United States 7th Division took over the base and hosted Soviet forces to discuss the terms of Korea’s division under their trusteeship. When three years of US military rule ended in 1948, South Korea inherited the military infrastructure, establishing the Capital Security Command and the Army Headquarters. Yet, peace was short-lived, as North Korea invaded the South in 1950 to unify the peninsula under the communist leadership, sparking three bloody years of the Korean War. In 1953, the US 8th Army moved into the base to deter the North’s future aggression. In 1957, the UN Command also relocated from Tokyo.

ITAEWON’S “MODERNITY”

Despite its vicissitudes stemming from Korea’s historical fragility and foreign powers’ ambition, Itaewon was Korea’s gateway to modernity and multiculturalism. Due to its centrality and proximity to Han River and Namsan Mountain, it served as one of four entry checkpoints into Hanyang, Seoul’s medieval name. Owing to the huge footfall from tourists and foreigners, barter shops thrived from very early on. During the Chosun Dynasty, Itaewon and its larger vicinity, the Yongsan district, threaded the entire peninsula, converging and crisscrossing goods and people from everywhere.

It developed as a port, where boats carrying grains from all over docked and traded. Merchants congregated here as their operational base. In the late 19th century, Germans, British, Chinese, and Japanese competed here for trade influences. One of the first steamships ever to cruise the Han River was dubbed Yongsan. The region also ushered in Catholicism, as France built Korea’s first Catholic school. By 1900, trams traversed Itaewon.

Itaewon has also shown how resilient the country can be, hot it can return memories to its rightful proprietor, and how the nation should chart its future course.

Eunwoo Lee

In the latter half of the century, the US presence came to the fore. The Seoul Museum of History states that the Americans from Yongsan Garrison created and shaped Itaewon as we know it today. In the 1950s, the US Office of Economic Coordinator located in Yongsan supervised Korea’s postwar reconstruction and US aid. Struggling artists milled around the base to sell portraits, laying the ground for Itaewon’s artistic heritage. Clubs in Itaewon hosted soldiers and singers from all walks of life reveling in rock, pop, and country, earning the nickname “Korea’s pop mecca.” It was from Itaewon that South Korea’s pop culture spread to the nation.

Yongsan Garrison and Itaewon also signified South Korea’s economic development and military sophistication. In recognition of South Korea’s speedy recovery from the Korean War, in 1978, Washington and Seoul instituted the Combined Forces Command in Yongsan to coordinate military plans and exercises on a more equal footing. In the 1960s, embassies sprouted in the neighborhood, kindling the construction of high-end living complexes. Itaewon specialized in catering to foreign populations with nationality-specific shopping districts. By the time of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, around 1,800 stores had opened in Itaewon. In other words, the world settled here.

SEAMY SIDES OF ITAEWON

Even as Itaewon bloomed on the outside, rot ran rampant underneath. Brothels appeared as US soldiers were given leave in 1957 to venture outside for entertainment. However, most “entertainers” or “comfort women” ended up there against their will. Until well into the 1980s, pimps and middlemen masquerading as career advisors abducted minors and vulnerable women, forcing them into prostitution. The South Korean government even designated some places as official “comfort facilities” for US soldiers, turning a blind eye to human trafficking and rape. The authorities regularly rounded up the women and screened sexually transmitted diseases. Refusing to cooperate or testing positive landed them in concentration camps.

Even as detainees died of penicillin overdose, government officials insisted that sexual services for the Americans were “an act of patriotism that brings in foreign currencies.” Some were dragged to mountains where the soldiers trained and were then raped under trees and in officers’ tents. It was only in September 2022 that the Supreme Court recognized the government’s complicity and atrocities and ordered compensation to the survivors.

Another issue has long plagued Itaewon. During the Korean War, a bilateral treaty in July 1950 granted the US forces fighting for South Korea all criminal jurisdiction over their soldiers’ conduct. Then in 1952, the two parties signed another treaty exempting US military personnel from civil litigation. After the war, the Mutual Defense Treaty of October 1953 paved the way for Washington to deploy and station its forces in South Korea indefinitely.

Even as detainees died of penecillin overdose, government officials insisted that sexual services for the Americans were “an act of patriotism that brings in foreign currencies.”

“Itaewon Freedom” has come to refer to the indemnity enjoyed by the US soldiers who assault, murder, or rape Korean citizens. The number of crimes has decreased over the decades, from about 2,000 per year on average in the 1970s, to 1,600 in the 1980s, to 800 in the 1990s, and to 400 in both the 2000s and 2010s. Although traffic violations and battery take the lion’s share, the long list of major cases involving murder and rape has enraged the Korean population. Meanwhile, cases of careless assaults left others permanently disabled.

Seoul and Washington signed the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) in 1966 to empower the former with a modicum of judicial powers over the soldiers. But in practice, it was just a formality. The US Army pressured South Korea’s justice department to drop countless cases. And before the revision in 2001, the Korean police could not detain the perpetrators until court sentencing. In the meantime, criminals walked freely in society or took flight. To this day, crimes committed on duty, as opposed to nightly carousing, fall within Washington’s jurisdiction.

The reduction in the annual numbers of SOFA crimes correlates with South Korea’s increasing rate of prosecution. For example, the prosecution rate had been below 1% in the 1900s, so low that Korean police officers even advised victims to give up reporting and pressing charges. Throughout the new century, the rate has gradually increased to 25%.

ITAEWON TODAY

As of July 2017, more than 60 years of the US occupation of Yongsan (and Itaewon) technically came to an end. More than 90% of US personnel and materiel from Yongsan Garrison had been packed off to Camp Humphreys, the largest overseas US military base, a one-hour drive south of Seoul. Multiple South Korean governments have tried to nudge US forces out of Yongsan since 1988, casting the matter as reviving national pride.

Their efforts paid off in 2004 when Seoul and Washington formally agreed to expand Camp Humphreys’s capacity and accommodation to absorb Yongsan forces. Yet, only 31% of the base territory — 154 out of 494 acres — has been returned to South Korea, as the rest awaits agreements on recompensation, environmental inspections and cleanup, and other security problems.

In May 2022, South Korea’s incumbent, President Yoon Suk-yeol, moved the presidential office and his entourage from the historic Blue House to the Ministry of National Defense premise in Yongsan. The transferred part of Yongsan Garrison turned into a park, which will expand as more territory changes hands. The Army Headquarters left the region in 1989, and Combined Forces Command followed suit in October 2022. Yongsan finally returned to civilian life for the first time in 144 years. Military police no longer roam the streets of Itaewon.

Itaewon looks to refashion itself. About 70% of people dining and drinking in Itaewon used to be American. Children used to go trick-or-treating on Halloween. Now, mostly Koreans and tourists enter the neighborhood for gastronomical snippets of the world. Changes in customer demographics have led to the appearance of snazzier restaurants using Instagram to attract the young. Itaewon is transitioning from mini-America to a place where Koreans savor different corners of the world.

However, it has not been without trouble. Although cases of assault and sexual harassment by US soldiers almost ceased, young Koreans and tourists are also capable of raising a ruckus with their excessive partying and noise on the streets. In 2020, at the height of COVID-19 lockdowns, the young populace defied distancing rules and went clubbing in Itaewon, leading to massive infections. Locals have come to resent their drunken screams.

This year’s Halloween tragedy illustrates as much. Pandemonium reigned as people deliberately pushed one another in disorderly crowds and urged others to keep moving even as people were dying up front. Meanwhile, only 137 police officers were present to regulate the crowd of more than 100,000. Plus, 50 of them were undercover agents, busting drug dealers.

Yet, the incident should serve as a lesson for future interactions in Itaewon rather than a cause to throttle its vibrancy. Halloween parties and nightlife signify South Korea’s embrace of multiculturalism and young people’s interest in the world. It is where people of different colors, origins, and nationalities accept differences and sing together in a predominantly homogeneous country. It is where young women feel safer and less self-conscious for dressing up the way they want without being judged. Gay bars and transgender clubs of Itaewon also mean that a conservative Korean society is indeed advancing to openness.

Young people flock to Itaewon to blow off steam amid excessive workloads and cut-throat labor markets. Outlandish faces and diners momentarily take them abroad, where they lose themselves in their imaginations and foreign tongues. All the more so on Halloween, when costumes and decorations fool everyone of where they are. This has been Itaewon’s appeal.

Itaewon has been many things and seen many faces. Empires have risen and fallen with Itaewon playing a role. Foreigners stayed and settled. Atrocities and injustices went unchecked. It indeed occupies a distressing part of Korea’s history. But this place has also shown how resilient Korea can be, how it can return memories to its rightful proprietor, and how the nation should chart its future course.

Itaewon may seem at a loss in the face of the changing environment. Yet, the fact that people of so many nationalities congregate here demonstrates Korea’s painful history of transforming into a better future, experimenting along the way, and feeling comfortable in the end. The Halloween crowd surge and deaths are truly grievous. The government needs to make it a lesson for enhanced crowd management, and young people should learn to value safety over entertainment. In the meantime, Itaewon’s spirit and its significance should live on.