Stepping down on the gas, Kaneki puffs a cigarette and navigates his pickup across southeastern Ukraine’s flatlands toward the road to Orikhiv. Early morning daylight is just beginning to brighten the skies above Zaporizhzhia.

The 24-year-old soldier shouts over the sound of the engine. “Israel against Gaza? It’ll quickly die down but can be bad for us.”

Kaneki is attached to Recon Team Kilo, a Ukrainian unit fighting in the south. Since the war between Israel and the Palestinian armed group Hamas broke out on Oct. 7, much of the world, including Ukraine, has turned its eyes toward the Middle East.

Nearly a month into that conflict, the Israeli military has launched a ground invasion into the besieged coastal enclave, home to more than 2.1 million Palestinians. Keeping a close eye on the fighting, some Ukrainians are optimistic, others less so. Many worry that the coverage of the conflict could eclipse international concern for their ongoing struggle. They worry about their legacy, and they worry about the ripple effects between the two wars.

As 40,000 troops sit poised to launch a third wave assault on Avdiivka (200 kilometers east of Zaporizhzhia), Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelenskyy yesterday tweeted his thanks to Japan and other Group of Seven nations for their, “unwavering support for Ukraine even amid other global developments.”

For his part, Kaneki worries that with the world’s attention fixed elsewhere, Russia could seize the moment to escalate its war on Ukraine. “I’m afraid that the Russians might use the media diversion to start doing dirty things, like using chemical weapons against us,” he says, exhaling slowly. The question of whether Russia has or will use chemical weapons is a pressing concern for analysts and researchers watching the conflict as well.

Strike, 38 years old, one of his comrades, fears being forgotten. “I’m just afraid that tomorrow, Europe and the United States might decide it’s no longer worth helping Ukraine,” he says, “and we’ll find ourselves having to stop waves of Russians without end.”

Both are skeptical, but more important to them than the potential fallout of the Israeli-Gaza war is the present moment in the Zaporizhzhia region.

“When you have your feet in the mud, you don’t think too much about that,” explains Kaneki. “You don’t even think about Ukraine, freedom, or victory anymore.”

It Could Be a Good Thing

Smiley, a former butcher turned machine gunner, is more pragmatic. He believes that the war between Israel and Gaza’s armed groups will benefit Ukraine. “The United States will never abandon Ukraine,” he says. “They’re not here for our good looks but because they have no interest in us losing.”

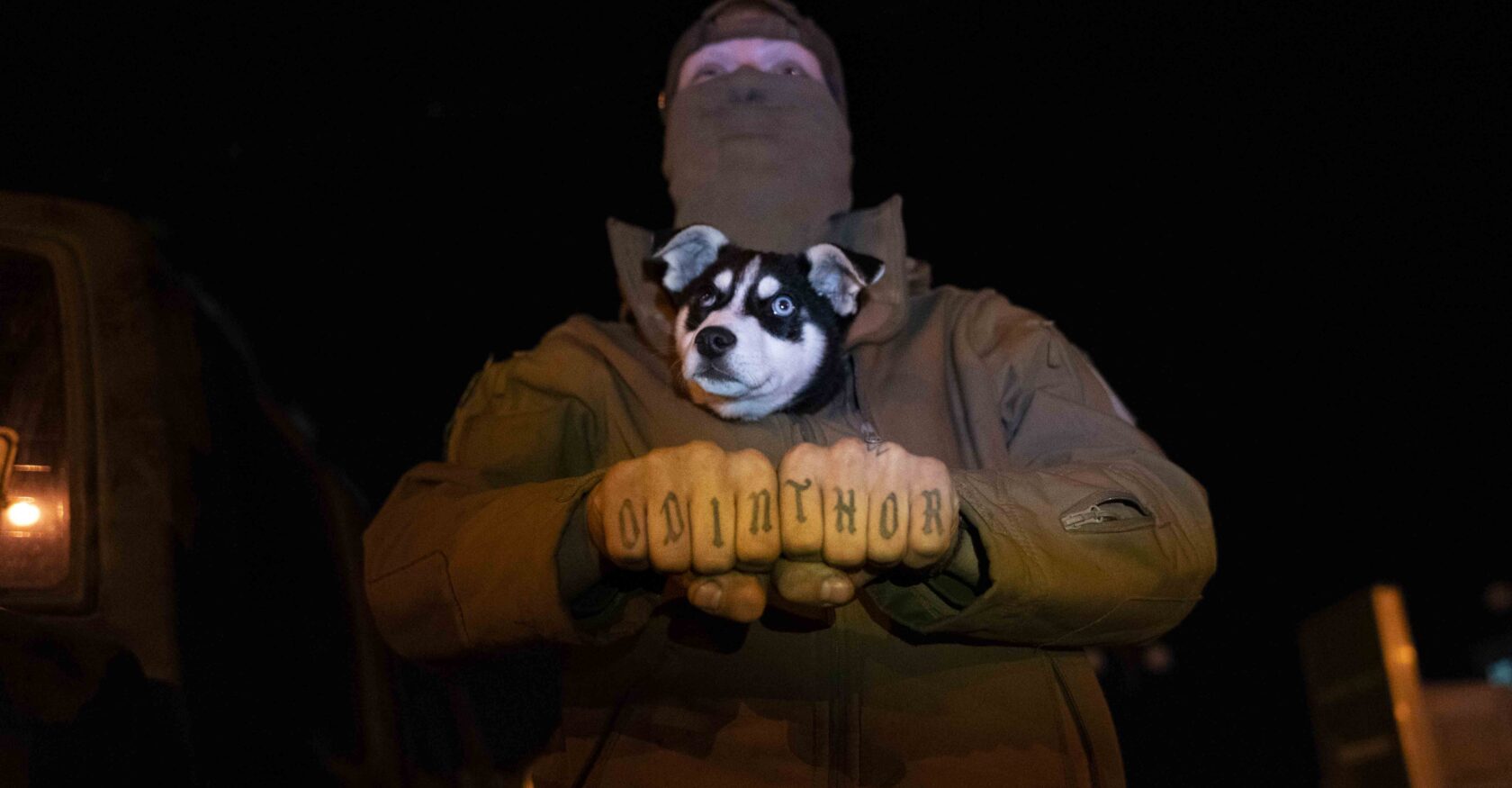

Smiley, 25, sports a long beard that softens an otherwise sharp face covered in tattoos. “The West is too involved to withdraw or reduce its assistance,” he continues. He pauses and takes a deep breath before arguing that the intensity of the conflict and the need for arms and equipment are radically different between Israel and Ukraine.

“Here, we need an astronomical amount of weapons, shells, human resources, and ammunition every day to face Russia,” he says. “Israel has one of the best armies in the world and is dealing with Hamas, a small terrorist group. We, on the other hand, are facing the Russian army; it’s not comparable.”