The year 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of when US troops left Vietnam and signed the Paris Peace Accords, establishing peace and ending the Vietnam War.

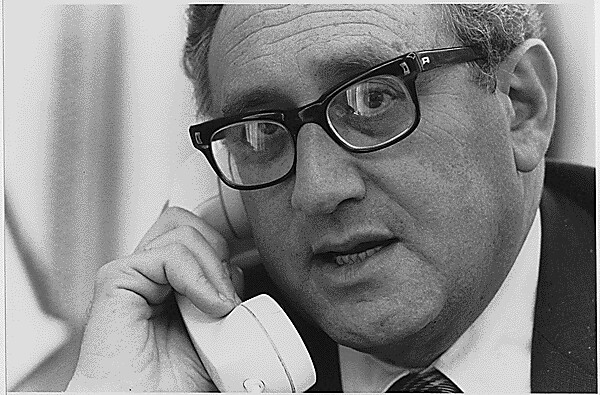

Henry Kissinger, who served as national security adviser and secretary of state under US President Richard Nixon, died last week. Kissinger had played a key role in the Vietnam War and had been the mastermind behind the destruction of my people’s homeland, Laos, as well as the architect of devastation in many other countries across the world.

After his passing, I am reminded of all the lives lost in Southeast Asia, the remaining remnants of war and the tragic history that led to my own family’s arrival in the US. If you ask any Southeast Asian American about their own story, the majority will reveal that their families had arrived in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the Cambodian genocide or the US Secret War in Laos.

I am uncertain how many people know this part of American history, but the US dropped eight million tons of ordnance onto Vietnam between 1965 and 1973. Many of those munitions are still littered unexploded across the country.

This year also marks 50 years since the last US bombs were dropped on Laos. From 1964 until 1973, the US dropped over 2.5 million tons of ordnance in Laos, making Laos the most heavily bombed country in history per capita. I only recently learned that the US also dropped over 2.7 million tons of ordnance onto Cambodia against Viet Cong forces, in an attempt to destabilize the country between 1969 and 1973.

This mass bombing of Cambodia’s countryside led to the rise of the Khmer Rouge, which subsequently carried out the destruction of Cambodian society and the genocide of an estimated two million Cambodians — a terrible tragedy that will stain the history of Southeast Asia and the world forever. A tragedy that organizations like Legacies of War — an advocacy group whose mission is to address the impact of UXO in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam and their diaspora communities in the US — hope to end in this lifetime.

But this is the part that gets often forgotten, especially when people like Henry Kissinger were responsible for these acts of mass destruction.

Displacement

Laos was my ancestors’ home before we fled to America. The home where my family led a quiet and sustainable life, farming crops, raising cattle and weaving textiles, where children roamed and played carefree before bombs were littered everywhere.

The total lives impacted is immeasurable and the death toll can never be certain, but it is estimated that at least 30,000 to 50,000 lives were lost alone in Cambodia due solely to America’s bombing campaigns. In Laos, approximately 30% of the over 270 million cluster munitions dropped did not explode on impact and tens of millions of unexploded ordnance still remain.

Many families did not survive the secret war back then. Five decades after the last bomb was dropped, families and civilians are still forced to navigate everyday life with risks of being maimed or harmed just by trying to live out their lives.

Those who made it to the US were forced to rebuild their lives with very limited assistance, resources and support along the way. Southeast Asian refugees faced significant barriers, including physical and mental health issues, like post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, stemming from their experiences escaping war, genocide, torture and mass starvation.

Five decades after the last bomb was dropped, families and civilians are still forced to navigate everyday life with risks of being maimed or harmed just by trying to live out their lives.

Additionally, many were resettled in communities that were heavily disinvested and lacked long-term resettlement support, leaving many to also suffer from systemic poverty, discrimination and linguistic barriers.

My own extended family had been trickling in as refugees since 1978, with the early resettlement programs beginning in Minnesota, Wisconsin, California and Texas.

Eventually, in the fall of 1981, my parents and their five young children were the first refugees from Laos resettled in Arizona. We were fortunate: while waiting in a refugee camp, we had been sponsored by an American family who generously treated us like family and was willing to do the challenging work of learning about us and including us in their community.

Repeating Mistakes

But many other families had little to no support and struggled immensely. I fear our government leaders are committing the same errors, once again, that Kissinger did and we must not forget the travesties that war brings on innocent civilians.

The administration of President Joe Biden continues to send cluster munitions to support the Ukraine effort, but is ironically now after years of advocacy, one of the biggest supporters/investors of UXO clearance in Laos and Southeast Asia. Moreover, the US also refuses to join the Convention on Cluster Munitions that prohibits the use of cluster munitions.

I believe everyone can generally agree that any war is bad. So, wouldn’t we want to do everything in our power to not repeat the mistakes and war crimes that stain Kissinger’s legacy? Let’s hope our leaders today realize sooner than later what lies ahead if they continue down this path of carpet bombing and using cluster munitions.

Editor’s note: Khamsone Sirimanivong wrote the personal anecdotes and experiences relayed in this article with the assistance of Pajouablai Monica Lee.