As intellectual and cultural milieus go, few compare with Vienna of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. A global city in the first truly global age. Its coffee houses were renowned for open-minded and intellectually fierce discussions, attracting a variety of thinkers, misfits, exiles and artists. The city gave its name to various schools of artistic and scholarly endeavor, the outputs of which resound through to the present, often in unnoticed and unappreciated ways. Much of this thinking, whether the economics of Hayek or the fascism of Hitler, seem – from our vantage – to form part of an immense and turbulent waterway carrying along the ideological driftwood of modern history; flowing at times toward freedom and self-expression, and, in darker moments, ebbing toward hatred and exclusion.

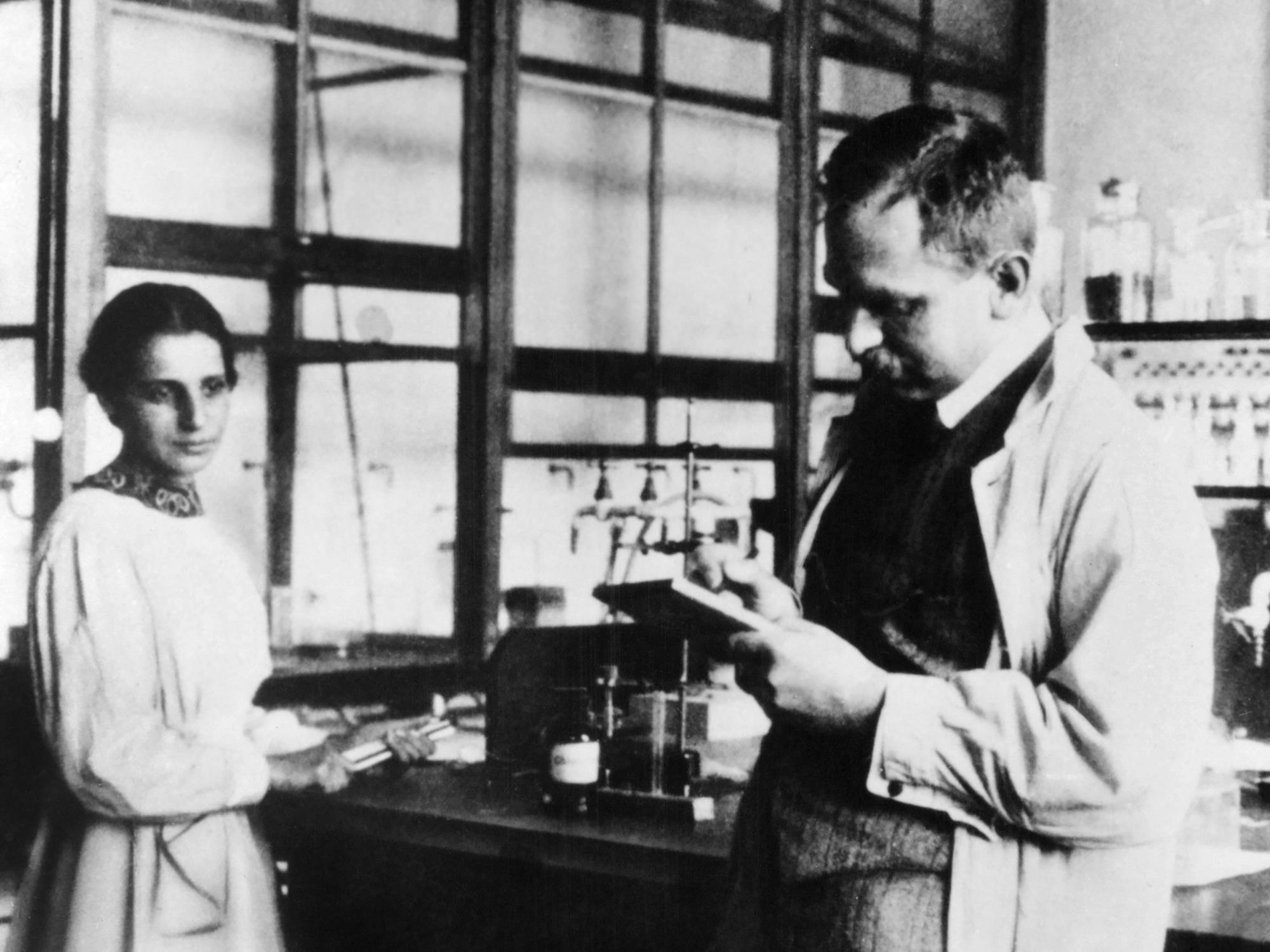

Perhaps the most overlooked product of this extraordinarily diverse environment was the physicist, Lise Mietner, who in 1907 became only the second female to earn a doctorate from the University of Vienna. Born into a prosperous Jewish family, Meitner showed an early aptitude for science and after completing her PhD, moved to Berlin to study under the famed physicist Max Planck. Despite Planck’s misgivings about female scientists, he took on the 28-year old Meitner as his teaching assistant and soon she was making a name for herself in the growing and increasingly competitive field of radioactivity. Her work of over three decades, much of it produced in partnership with Chemist Otto Hahn, culminated in the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938 – the process at the heart of our modern use of nuclear energy and, of course, atomic weapons.

Meitner stayed on in Berlin after the Nazis came to power in 1933, she stayed on – protected by her Austrian citizenship – even after the Nuremberg laws of 1935 stripped Jews of their citizenship and barred them from public office. Finally, and almost without warning, she was forced to flee after being rendered stateless and utterly vulnerable by Hitler’s annexation of Austria in March 1938. It took mere hours for anti-Semitic violence to break out on the streets of Vienna and within a matter of weeks, Jews had been removed from almost all professions, banned from universities and forced to wear the yellow Star of David. Over two hundred thousand Jews lived in Vienna before the Second World War, by 1945 only hundreds remained; many fled seeking refuge elsewhere in Europe or America, but tragically over sixty thousand were sent to their death in Nazi extermination camps.

In 1942 the Americans asked her to collaborate on the Manhattan Project, but true to her pacifist ideals, she refused, declaring that “I will have nothing to do with a bomb.”

Meitner escaped to Sweden via the Netherlands, all the while conscious of the contrast between the places she had once known and the places they had become. Upon reaching safety, she wrote to a friend that ‘one dare not look back; one dare not look forward’. Darkness, it must have seemed, was all around her.

In 1942 the Americans asked her to collaborate on the Manhattan Project, but true to her pacifist ideals, she refused, declaring that “I will have nothing to do with a bomb.” She spoke out repeatedly throughout her life about the threat posed by nuclear weapons and spent many years after the war persuading former colleagues to accept responsibly for collaborating with the Nazis. An epitaph on her gravestone in rural England simply describes her as ‘a physicist who never lost her humanity.’

The work of Lise Meitner is worthy of our attention, worthy of greater recognition. But just as noteworthy, just as instructive is the geography of her life: Vienna, Berlin, Stockholm and finally to England where the arc of her long life descended upon Cambridge; a refuge of reasonableness from the madness that had ruined the places and spaces of her youth. There she joined what remained of her family who had chosen Britain as their preferred shelter, just as other, more famous, Viennese asylum seekers had: Freud, Wittgenstein, Popper among others. It is hard not to wonder whether their successors would likewise pick post-Brexit Britain – or, for that matter, Trump’s America – as their sanctuary from whatever calamity, nuclear or otherwise, may lay before us.

It was another European exile, Joseph Conrad, who, in his most celebrated novel, Heart of Darkness, imagined a pall of darkness looming over London, prompting his protagonist to consider the narrow gap between Britain and the primitive world beyond; between civilization and savagery. Such imagery may seem banal and overwrought when used to describe our own times, but it does bring an important truth to mind. It was a nightfall, not unlike the one descending now, that consumed Berlin and Vienna – places that had nurtured some of our most treasured ideals. And we too find ourselves suddenly unmoored from our cosmopolitan conceits, drifting with the ebbtide toward the darkness that lies – as Conrad knew – uncomfortably close to home. If Meitner’s story has any relevance for us at all, it is surely as a warning, one that brings forth a dread-ridden realization – we have been here before.

Peter Waring is a senior researcher at Ridgeway Information where he focuses on non-proliferation and regional security, primarily in the Middle East. He holds an MA in Strategy and Security from the University of New South Wales and an MA in Geopolitics, Territory and Security from King’s College London. Before moving to London, Peter spent over a decade as an officer in the Australian Navy during which he served in the Middle East, Antarctica and South-East Asia.