The US-backed Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet established over 1,200 detention, torture, and extermination centers across the country. Three of these centers were navy ships docked in the port of Valparaiso: the Lebu, the Maipo, and the Esmeralda. According to records, the dictatorship detained some 5,500 political opponents on these vessels — 500 of them aboard the Esmeralda.

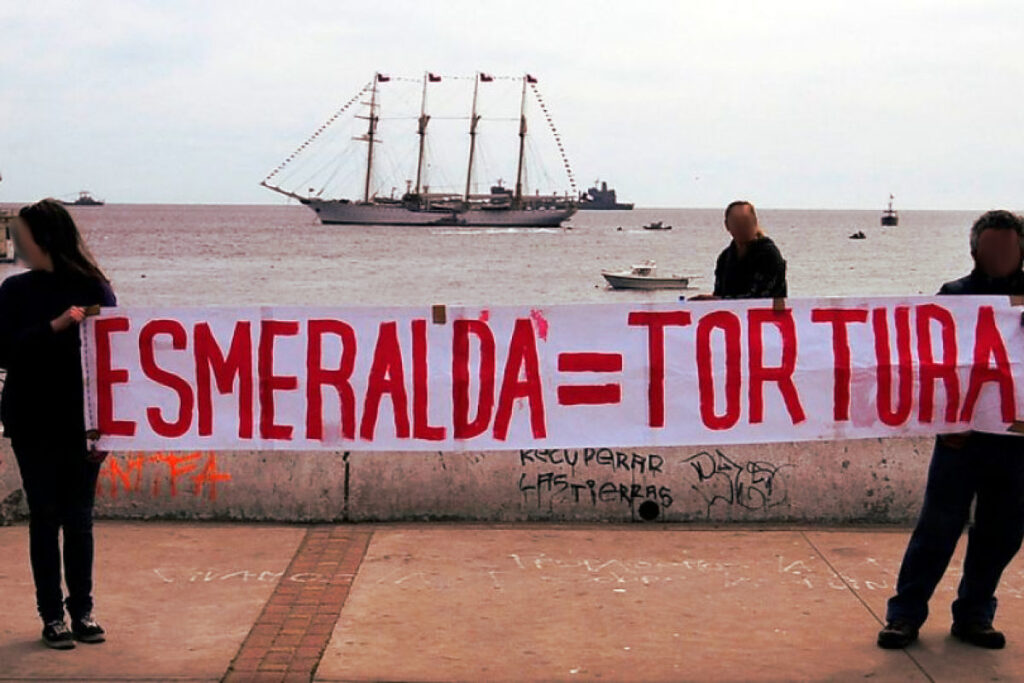

Chile’s navy now uses the Esmeralda in diplomatic and training endeavors, whitewashing its dark past. Earlier this month, the Esmeralda docked at Portsmouth, prompting Chilean exiles in the United Kingdom to protest against the vessel’s presence, given the history it harbors.

“The blood of our brothers and sisters have stained that ship, and it will never be clean again,” Maria Pelusa recently told Portsmouth News. She is one of the Chileans protesting the ship’s presence, and her brother was executed by the dictatorship in October 1973. “She’s called The White Lady, but it’s neither white, nor pure, it is a center of torture. We want the young Chilean people and the young British people to know history and to never allow for that history to be repeated again.”

Dismissing the ship’s dictatorship history, as well as the Chileans’ concerns, a spokesperson for the UK Royal Navy said in a statement, “The Royal Navy has welcomed the Chilean ship Esmeralda to Portsmouth and the opportunity to strengthen ties with our long-standing and reliable ally in South America.”

Bodies Thrown Overboard

The UK navy’s dismissal also ignored the fact that one of the dictatorship’s victims tortured on board the Esmeralda was the British-Chilean priest Miguel Woodward Iribarry. Iribarry was a member of the Popular Unitary Action Movement (MAPU), which was formed in 1969 in affiliation with the Christian Democratic Party, and later became part of Salvador Allende’s left-wing Popular Unity coalition.

Iribarry was one of those summoned over loudspeakers in the immediate aftermath of the coup and, having ignored the order, was arrested on Sept. 22, 1973. Detained and tortured aboard the Lebu, he was then transferred to the Esmeralda, where after severe beatings, a doctor certified him as having less than an hour to live. Iribarry died on the way to the Naval Hospital at Plata Ancha and his body ended up buried in a mass grave. In later years, the site was marked for construction and several bodies of the disappeared were thrown into the ocean or dissolved in acid by the Chilean police.

The Valparaiso newspaper La Estrella first reported Iribarry’s detention that same month, despite all media having already come under state control. His family, however, only learned about his detention, torture, and death in 1975 after reading an article in a British newspaper, as the state communicated Iribarry’s cause of death as cardiac arrest.

It was in 2004 that the head of the Chilean Navy, Miguel Angel Vergara, acknowledged for the first time that dictatorship opponents were tortured on the Esmeralda, after then-President Ricardo Lagos released a report on the torture of political prisoners during the dictatorship.

Right-wing Inroads in Valparaiso

In August 1967, Agustin Edwards, the business and newspaper mogul who played a major role in orchestrating the 1973 coup, set up the Cofradía Náutica del Pacífico Austral (or Nautical Brotherhood of the Southern Pacific). The organization brought together prominent neoliberal admirals, businessmen, and bankers who plotted the coup together with Edwards.

Attending the first meeting were Hernán Cubillos Sallato, Enrique Puga, Bendro Drummond, José Toribio Merino Castro, Oscar Buzeta, Eric Weber, Isidoro Melero Rodríguez, John Hardy, and Roberto Kelly Vásquez.

That same year, those who attended the founding meeting were tasked with inviting other naval partners and “to sponsor the training ship Esmeralda to provide maximum support for its role of spreading the Chilean nautical spirit.”

The blood of our brothers and sisters have stained that ship, and it will never be clean again.

– Maria Pelusa

By 1968, Colonel Sergio Arellano Stark had become military aid to President Eduardo Frei Montalva, and the Nautical Brotherhood had expanded considerably, now including Patricio Carvajal, Arturo Troncoso, Pablo Weber, and Ismael Huerta — all of whom played a role in the 1973 coup. It was in 1972 that Kelly included Arellano in the Nautical Brotherhood, thus facilitating the link between the Maipo regiment Arellano commanded and the naval bases in Valparaiso.

Civilian entrepreneurs also joined the organization, among them Ricardo Claro, owner of Cristalerias Chile and later the main financier of Augusto Pinochet’s National Intelligence Directorate (DINA). Claro also owned the company Sudamericana de Vapores: the Lebu and the Maipo were part of the fleet and, according to investigations Judge Juan Guzman conducted, the ships were also used to disappear the bodies of dictatorship opponents, alongside the more well-known death flights.

From Plotting Coups to Eliminating Opposition

Anti-communist José Toribio Merino Castro, who self-appointed himself as commander-in-chief of the Chilean Navy on the day of the coup, is credited with planning the coup that ousted President Salvador Allende and convincing Pinochet, then commander of the Armed Forces, to join in.

While the military turned its attention on Santiago, bombing the presidential palace, Merino was in charge of the naval blockade in Valparaiso. While the navy besieged the port, sailors were tasked with detaining Chileans who supported or were members of several left-wing parties, as well as workers who benefited from Allende’s agrarian reform and the nationalization of the copper industry. The navy also conducted a purge of its own ranks, detaining officers and sailors who opposed the coup.

A former detainee who was tortured by the Navy at the Playa Ancha War Academy, stated of Merino, “He was the one in charge; nothing was done without his knowledge.” Nicanor Diaz, Pedro Quintano, Franklin Gonzalez, Raul Lopez, Marcos Silva Bravo, Jose Yanez Rivero, and Jose Garcia Reyes are among the officers responsible for the torture, extermination and disappearances of socialist and communist adherents on the Esmeralda.

US Attempts to Discredit Survivors

Sergio Vuscovic Rojo, the former mayor of Valparaiso, was among the first torture survivors to give testimony in October 2018 on board the Esmeralda itself, corroborating the experience with a tour of the ship, indicating the different places where the detainees were tortured.

In a declassified cable to the US Secretary of State from July 1976, the US embassy in Santiago attempted to discredit the testimonies of survivors. While not outright excluding the possibility of torture aboard the Esmeralda, the cable noted, “We believe, however, that the sources of the accounts have strong reasons to fabricate or greatly exaggerate examples of mistreatment. We suggest that their accounts be taken with much caution.”

Yet, just a month earlier, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had warned Pinochet about the accusations of human rights violations. And the atrocities aboard the Esmeralda were part of the initial purge, preceding even the well-known Caravan of Death, a helicopter squad that flew from the north to the south of the country killing workers and Allende supporters.

“Until His Organs Burst”

On the Esmeralda, Iriberry was beaten “until his internal organs burst,” according to testimonies provided to Memoria Viva. Other firsthand accounts compiled by Memoria Viva, which is dedicated to the collective memory of the dictatorship era, corroborate Iribarry’s treatment.

Per Memoria Viva, Luis Vega, a torture survivor who endured torture on the Esmeralda, recalled severe beatings to the kidneys and grotesque costumes and masks worn by the torturers. Detainees were hit by pressurized water which pierced the skin on his face and details the symptoms associated with waterboarding from the water pressure. For a whole night, Vega states, the detainees were “beaten and taken to the showers every five minutes.”

Also speaking to Memoria Viva, female torture survivor Maria Eliana described her ordeal on the Esmeralda. Eight officers wearing hoods or with their faces painted black forced her to strip completely naked, which she refused, given that she was menstruating. She was sexually assaulted and humiliated — “Such was the moral quality of the admiral’s sailors,” she recounts, while noting that the violence continued unabated.

“They took out the companions, beat them, tortured them, they came back purple and vomiting blood,” Eliana explained. From the Esmeralda, she was transferred to the Lebu, where the sexual torture continued. Eliana was also witness to Vuscovic’s arrival on board the Esmeralda.

History Ignored

Despite testimonies concerning the Esmeralda having been recorded by the Rettig Commission Report, Chilean governments since the transition to democratic rule have failed to acknowledge the Esmeralda’s role in the dictatorship. The ship regularly sails around the world on missions that represent Chile and the Navy, yet neither the Chilean government, nor the governments where the ship docks, link the Esmeralda to the dictatorship.

Former Chilean President Ricardo Lagos is perhaps the biggest example of oblivion — a term coined by Pinochet to encourage Chileans to embrace forgetting the dictatorship years to ensure impunity — when he hailed the Esmeralda’s voyage in 2003 with words that lauded the ship while ignoring its horrific past. “A nation proud of what you are doing sets sail together with you. You will arrive with the pride that embodies a country, which is a small star in the southern hemisphere that is respected for its democracy and human rights,” Lagos lauded.

The Esmeralda’s victims and their families beg to differ.

Top photo: A photograph from June 2012 shows the Chilean Navy’s Esmeralda docked (David Edwards via Wikimedia Commons)