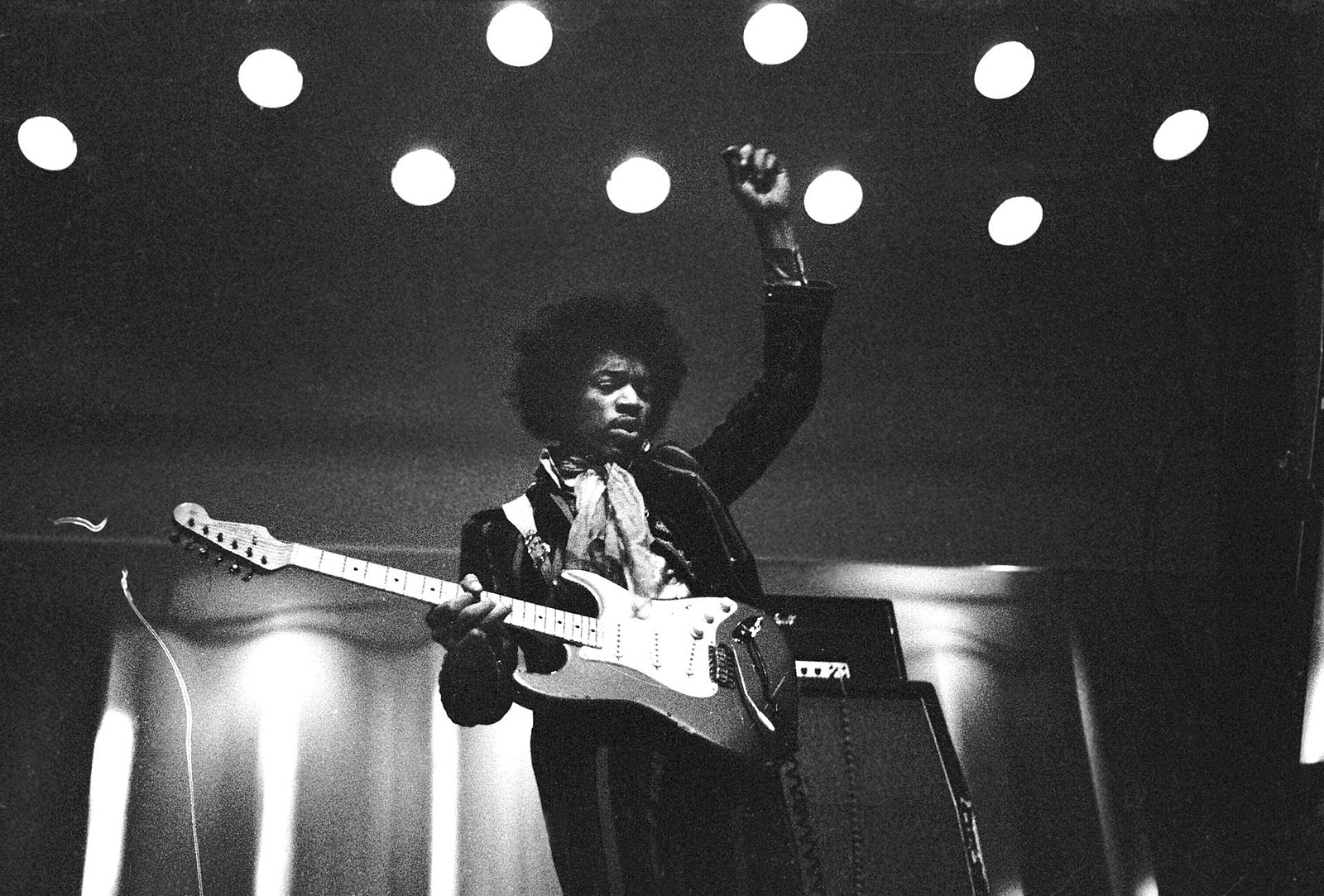

It was autumn 1968. The newly commissioned HMS Repulse (S23) slipped silently out of the Firth of Clyde and dove deep under the sea on the first patrol of the United Kingdom’s nuclear continuous-at-sea deterrent (CASD). The vessel carried 16 A3 Polaris Missiles armed with three ET317 warheads, the anglicized version of the American W58 weapon, with the capacity at any given moment to deliver 16 megatons of nuclear ordinance onto predesignated targets in Soviet Russia. Meanwhile, far across the world in Los Angeles, rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix deployed a fierce new electro-acoustic guitar music upon audiences. Like the sonar subsystems on HMS Repulse, these new guitar sounds found their origins in the acoustic laboratories at the UK Admiralty Research Laboratory (ARL) in Teddington, South West London.

Jimi’s guitar sounds were the result of a collaboration with electrical engineer Roger Mayer, who had recently quit his job at ARL to provide technical support for Jimi Hendrix on his 1968 world tour. Roger had worked in the Noise and Acoustics group at ARL. However, in the evening he hung out with friends, and soon to be Yardbirds, Jimi Page and Jeff Beck, designing and building their guitar fuzz pedals. This would become a signature sound of the so-called “British Invasion” of the United States. In an interview for Reverb.com, Roger said that his experience of working with vibration and noise at ARL was ideally suited to inventing tones for electric guitars. Roger’s growing reputation led to a meeting with Jimi Hendrix at a London nightclub in 1967. Jimi and Roger had a shared interest in science fiction, and the guitarist described how he would like his guitar to sound like an alien invasion from space. Two weeks later, Roger invented the Octavia guitar effect pedal for Jimi. The Octavia worked by splitting Jimi’s guitar signal into three distinct octaves to create the iconic guitar sound of Purple Haze, which came to define the broad cultural memory of the 1960s psychedelic counter-culture.

These meetings are not quirky anomalies. In 1970, the Karman Nuclear Corporation, which amongst their many ventures produced nuclear threat computer models for missile defense war games run by MIT Lincoln Laboratory, bought the National Music String Company of Brunswick, New Jersey. The result was the formation of a subsidiary company called the Karman Music Corporation (KMC) that Fender bought in 2008 for $117 million. KMC used company experience and knowledge of composite materials to produce roundback guitars preferred by artists such as Glen Campbell, Joan Armatrading, John Bon Jovi and Paul McCartney. Such instances of the influences of nuclear material technicity upon our shared cultural experiences occur with regularity, but epistemic norms and conventional wisdom of both the academy and everyday lifeworlds hide them entirely in plain sight. After several years of investigation, they are revealing themselves to me by using music as an innovative social research method.

The social structures of nuclear war fighting do not always remain internal.

I am an artist and academic using creative practice as an investigative tool to understand the way nuclear weapons and practices of nuclear deterrence have shaped our lives. As an artist in residence at RAF Fylingdales, I work with an interdisciplinary research team from Newcastle University. RAF Fylingdales is a Ballistic Missile Early Warning Station (BMEWS) that sits on the edge of the North York Moors. Since becoming operational in 1963, RAF Fylingdales, along with USAF counterparts in Greenland and Alaska, has unceasingly performed its twin missions of looking for signs of nuclear attack from space and monitoring the increasing amounts of human-made objects in low Earth orbit. Over the station’s operational life, individual engineers and service personnel amassed an archive of materials produced over their working lives. The archive will soon be available to a global public through the online Fylingdales Archive.

Amongst the artifacts is a large klystron amplifier and various parts of sub-systems used to generate powerful radar beams. During the Cold War, there were fears that Soviet trawlers in the North Sea would attempt to jam the radar. I wondered if I could use creative practices to materialize these electromagnetic military engagements.

To do so, I formed a band with music producer Chris Tate called One Key Magic (OKM). Although not an obvious approach, it made sense because Radio Corporation of America (RCA) – better known for making iconic sound recording equipment such as the velocity microphone and 45 vinyl single – had designed and built the BMEWS project at their factories in Moorestown (now Lockheed Martin) and Camden (now L3 Harris), New Jersey (NJ). It turns out that there are processes common to both radar operations and recording studio practice, such as monitoring frequencies and adjusting harmonics. For example, the klystron amplifier, which was used to generate the powerful radar beam at RAF Fylingdales, essentially did the job same as a vacuum tube in an old electric guitar amplifier. What has emerged is a collection of music produced using these shared techniques and processes, and formed from the drones and timbres of electronic phenomenon. The ultimate result is more than a curious aesthetic experience or several subjective artworks. Rather this musical collection reveals how historic defense technologies have acted upon our everyday lives through discreet relationships between the defense and music industry.

It seems an unsettling notion that the music of treasured formative experiences could be connected to the mechanisms of nuclear war fighting. It feels like industries established for enabling warfare should be the very opposite of those that produced, for example, the Beatles’ “All you need is Love.” Nuclear weapons seem especially separate from the joys of music. Writing in 1980, sociologist and music journalist Langdon Winner said that because of the unique danger nuclear weapons posed to society, the bomb requires a centralized and highly authoritarian social structure, which is deeply internalized and distinct from the outside world. Yet the artifacts in the Fylingdales Archive suggested this was not necessarily the case. The social structures of nuclear war fighting do not always remain internal. Instead, they can leak into our life worlds, in this case through the seemingly unlikely route of the recording industry.

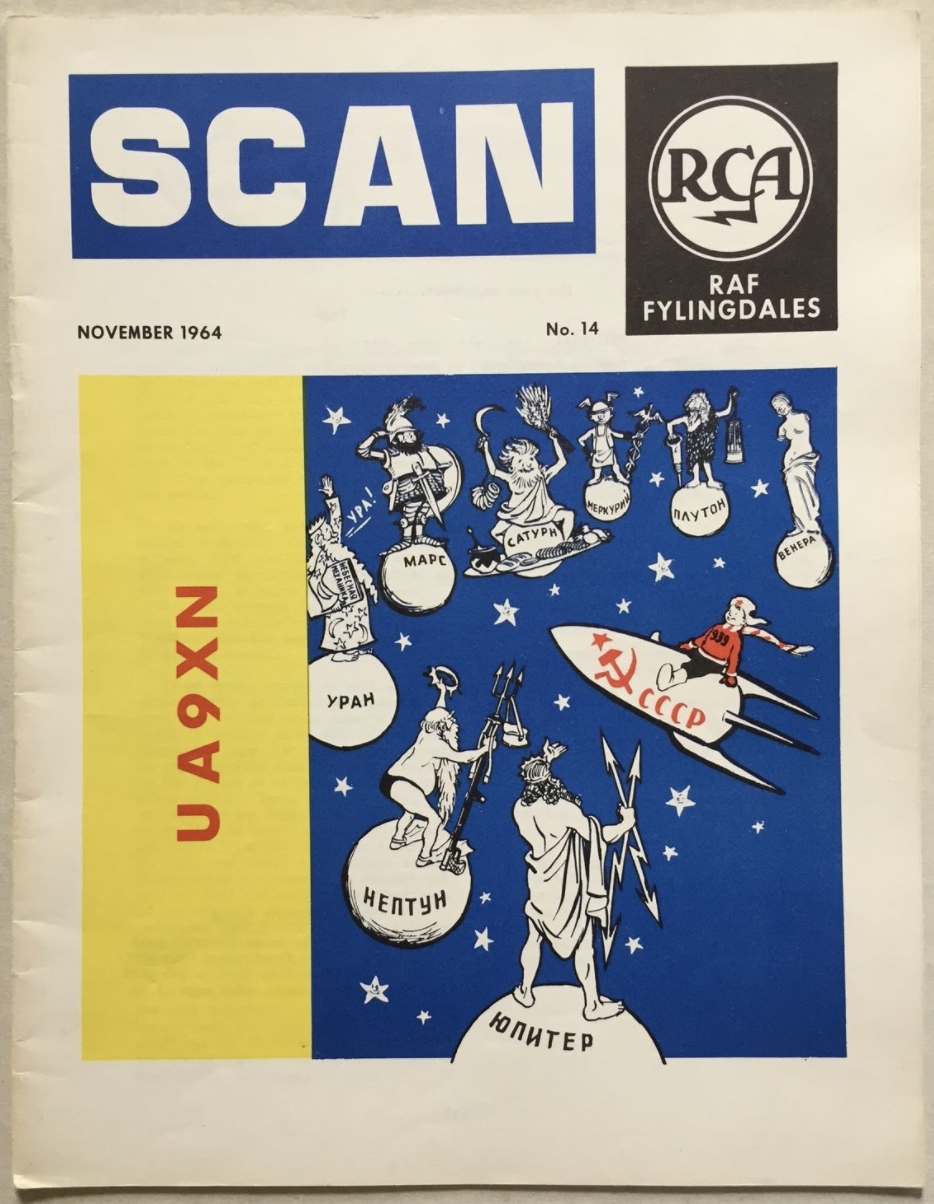

The role of Radio Corporations America on operations at RAF Fylingdales is literally inscribed on almost every item in the Fylingdales Archive, as you can see in the photograph below. This includes many documents relating to the activities of the RCA Service Company headquartered at Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

SCAN Magazine with RCA thunderbolt logo published for RCA Great Britain contractors at RAF Fylingdales. Fylingdales Archive. Photo: Michael Mulvihill

The company oversaw the construction and then the operations of BMEWS and managed many government contracts including those for NASA and the Kwajalein Missile Range (now Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Range) in the Pacific Ocean. In the UK, this work was done through RCA Great Britain (RCA GB), which prior to Fylingdales had been a small business that serviced sound equipment in the British film industry. BMEWS and other lucrative defense contracts allowed the RCA GB to expand rapidly into non-governmental sectors, which included color television manufacture, TV broadcast, and the record industry. The Fylingdales Archives shows that the UK division of RCA records emerged directly from the administrative structure used to supply and maintain ballistic missile warning system operations at RAF Fylingdales. RCA used these systems to distribute iconic records by stars such as David Bowie, Iggy Pop and ABBA. The success of RCA record division in the UK and their roster of stars outshone their major defense activities so much so that few outside of the Ministry of Defense were aware that RCA had a major role in maintaining nuclear deterrent structures.

My aim is neither to elevate nor put a positive spin on the existence of nuclear weapons, nor expunge artists upon whose work found audiences through defense sector players. Rather, I hope to show that outside of the glare of rock stardom, or the exceptionality of nuclear military technologies, knowledge and techniques can transgress the seemingly common-sense structures that organize the world. The artifacts in the Fylingdales Archive show that mechanisms intended for maintaining nuclear deterrence also had an unintended role of producing life experiences and shaping new identities for thousands of people across the world through music. Military and civilian worlds are less distinct than commonly imagined. In the case of Roger Mayer’s story, it was insights and techniques from the acoustics and electronic resonances of submarine warfare that opened the mind-altering spaces of the psychedelic counterculture of which ‘Purple Haze’ is not just an anthem but the sound of a new way of life. For myself, the electronic atmosphere and radar operations at RAF Fylingdales have offered a way of using music to make the activities of nuclear deterrence at RAF Fylingdales tangible in our lives. Even when nuclear weapon systems seem far out of sight, we should remain aware that they are nevertheless at work transforming our world and structuring our lives in unexpected places and in unimagined ways.

Dr. Michael Mulvihill is an Artist and Associate Researcher based in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University, UK. He is a Co-Investigator on Arts and Humanities Research Council’s (AHRC) funded project Turning Fylingdales Inside Out: making practice visible at the UK’s ballistic missile early warning and space monitoring station (AH/S013067/1) in partnership with RAF Fylingdales and English Heritage. In addition, Michael was Associate Producer on the BBC Four Arena film A British Guide to the End of the World (2019) that is based upon his doctoral thesis “The Four Minute Warning Drawing Machine: Revealing the Assemblages of Nuclear Deterrence.” Listen to “One Key Magic” and find out more about the Fylingdales Archive at fylingdalesarchive.org.uk