This analysis was featured in Critical State, a weekly newsletter from Inkstick Media and The World. Subscribe here.

The modern M1A2 Abrams tank, fielded by the US military and some allies, weighs over 73 tons. It gets, at best, 0.6 miles per gallon on jet fuel and consumes at least 300 gallons of that fuel every eight hours it is in the field. Transporting the tanks by air means fitting one into a large C-17 four-engined cargo jet, or two inside a massive C-5 jet. The tanks can also be brought close to where they’re needed by rail and ship, though that’s slower. When the US Army goes to war, it can do so with hundreds of these tanks.

The Abrams isn’t mentioned by name in “Disentangling the US military’s climate change paradox: An institutional approach,” a new paper by authors Corey R. Payne and Ori Swed, but they do mention the Bradley, another armored vehicle that has poor fuel mileage. Like the Bradley (a mere 28 tons and 0.9 mpg in the new hybrid version, according to the authors), the Abrams is but one small part of a vast fossil fuel-emitting military.

One reason given for why the military is so perceptive on climate change is because there are many military bases, especially ports, which are directly threatened by climate change.

The US military, to its credit, has identified climate change as real — and a threat — for at least two decades, weathering changes in presidents and shifting political attitudes toward climate action. Yet, the military’s role in contributing to climate change is understudied.

“We are thus left with a paradox: the military is one of the world’s major drivers of ecological degradation, while at the same time is one of the few powerful institutions in the United States that has been willing to acknowledge the dangers posed by the climate crisis,” write the authors. “Our review finds that the military does not see saving the planet from a climate catastrophe as a goal that falls within its mandate. Instead, military officials understand the climate crisis as a threat to national security that has to be dealt with.”

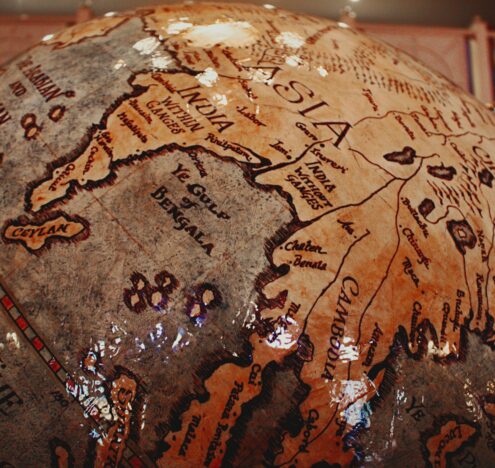

One reason given for why the military is so perceptive on climate change is because there are many military bases, especially ports, which are directly threatened by climate change. The United States operates roughly 800 bases around the world, all nodes in a great logistics chain that ensures soldiers have food, vehicles have fuel, and sensors like radar have electricity.

“Any mitigation measures embraced by the Pentagon are thus necessarily limited by the apparent conflict between military effectiveness and emissions reduction,” write the authors, who go on to argue that the overriding logic of the US military is to preserve its ability to fight and mitigate only as a secondary concern. As much as there is a conflict between the two measures, it is one largely internally resolved.

The greenest thing the military could do would be a strategic retreat that contracts its worldwide presence, argue the authors, thus mitigating the need to ship and sustain gas-guzzling tanks across the globe. What the military should be doing, instead, is investing in ways to deliver the same firepower, but from slightly more fuel-efficient vehicles, if possible.