One of the most famous representations of nuclear war remains John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” a 1946 New Yorker article turned best-selling book that chronicles the stories of six survivors. In response to the article, Mary McCarthy commented, “To have done the atom bomb justice, Mr. Hersey would have had to interview the dead.” Her comment forces us to confront the very possibility of ever representing the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The dilemma is stark: if no representation is possible after nuclear war, there remains nonetheless a duty to speak. To speak so as to bear witness. But how? How can testimony escape the idyllic law of the story?

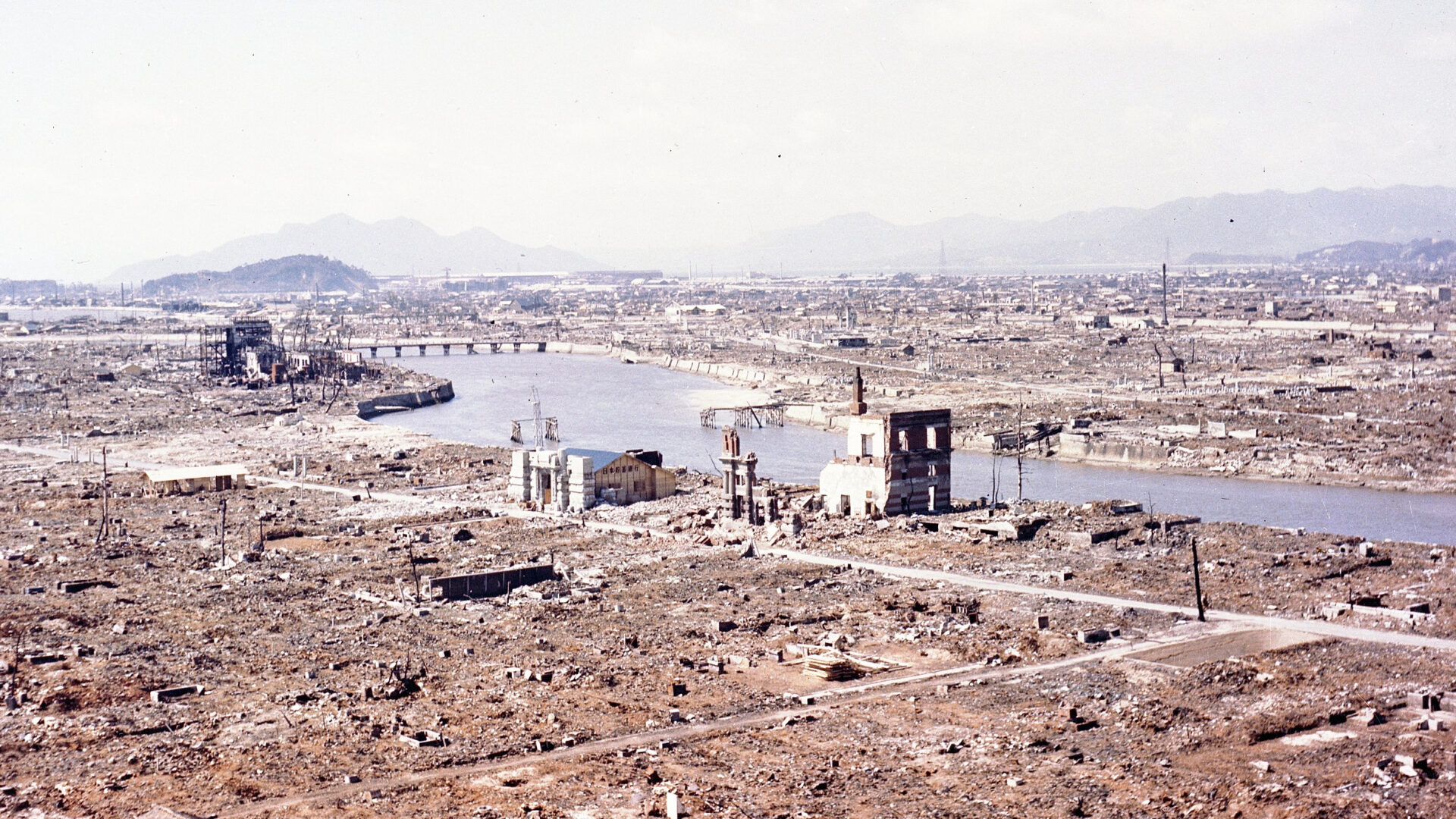

Can Hiroshima and Nagasaki be “truly” represented? How do we bear witness to such an event? What does this look like? Does it need to be heard, watched, or read? Does it require facts and figures? Testimonies or eye-witness accounts? Photographs or relics? Is a death toll a more “truthful” representation than a child’s drawing? Do the logbooks from Enola Gay hold more “truth” than a melted wristwatch?

Both artifacts have recently been sold at auction.

Enola Gay was the name given to the US B-29 Bomber that dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, killing up to 146,000 people, on Aug. 6, 1945. The plane was named after the pilot’s mum. Bidding started at $400,000 for the in-flight documentation made by Enola Gay’s co-pilot, Captain Robert A. Lewis at the request of journalist William Laurence of The New York Times. Heritage Auctions sold the logbook in 2022 — it was valued at $543,000.

“Immense in Significance”

Although easily assumed junk, the second artifact — a melted wristwatch — was described as “immense in significance […] a historic artifact that is among the more evocative objects to exist.” The watch hands read 8:15 AM, the time when Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb. The melted watch is believed to have been “recovered” by a British soldier from Ground Zero, Hiroshima. It was sold by RR Auction in 2024, valued at $31,113.

While the auctioning of the logbook sparked little controversy, the private profiteering from a watch stolen from a victim of a war crime sparked outrage in response. Despite many calls for the watch to be displayed in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, it fell into the hands of the highest bidder (who wished to remain anonymous).

Do the logbooks from Enola Gay hold more ‘truth’ than a melted wristwatch?

Both those who called for the watch to be memorialized and those who saw “value” in its melted face and clouded crystal resonated with the same thing: the story the watch told.

While the story told by an in-flight logbook is textual, pragmatic, and factual, the story the watch told is emotive, affective, and unknown. The auction house tells a story of an artifact “frozen at the moment of detonation” and media headlines report that it is “frozen in time.” Language such as “broken” or “destroyed” would carry less sentiment.

That time can stop, the world can stand still, and a moment can freeze are all metaphorical expressions of a perception, an embodied feeling, that we experience when we encounter something that evokes a sense of revelation.

“The End of Everything”

Where the logbook can help us to know more, the watch leaves us wondering about what can never be known. Without words, the watch can tell a thousand stories — none truer than another. Perhaps our own imagination and contemplation can more truthfully represent nuclear war than facts and figures.

More than six decades ago, philosopher Gunther Anders worried that our nuclear capabilities had surpassed our capacity to imagine the potential catastrophe — producing an effect he described as a “not-imagined nothingness.”