I don’t remember September 11, 2001.

My parents say I visited my preschool for the first time that day — the same preschool they picked me up early from just in case there was an attack in Chicago, too. It’s weird because I remember so much from that time in my life (I was three years old). I remember my teachers, Joseph and Anita. I remember the friends I played tag with in the gymnasium. I remember building castles that inevitably crumbled in the sandbox, sitting on the green rug for circle time, and acting out a scene from “Sleeping Beauty” with a boy who gave me my first Valentine’s Day card. These are some of my most vivid early memories. And yet, I don’t remember the day that shaped the world I came of age in and occupy today.

Over the next several years my generation — the one that doesn’t remember 9/11 — needs to unlearn the status quo of the last two decades.

In the wake of the PATRIOT Act, I learned that privacy should not be expected. In fact, I still operate under the assumption that the government (and Big Tech) know more about me than I do about myself. At a young age, I became a pro at going through security lines quickly — I knew to keep the quart-sized liquids bag in the outer pocket of my carry-on, to wear slip-on shoes, and to make sure my pockets were empty. These days I have TSA PreCheck, so all the years I spent rehearsing my role in the security theater have gone out the window. (No more placing my laptop in a separate container!)

More than the surveillance or the security, it was the wars that began in the aftermath of 9/11 that had a profound impact on my life, even though I didn’t have a direct connection to them; no one from my family or inner circle served overseas. In fact, the only person I knew who deployed was a friend of my dad’s whom I’ve never met. But each day while riding in the back of the car to school, I’d hear the reporters on NPR talk about the number of American casualties or the Improvised Explosive Device explosions or the territories lost and gained that day. When I first became aware of what those numbers meant, I felt distressed. How could this many people be dying every day? How could it become such a normal part of life? How could we compress the war’s far-reaching magnitude into a single sentence at the end of each newscast before the traffic report?

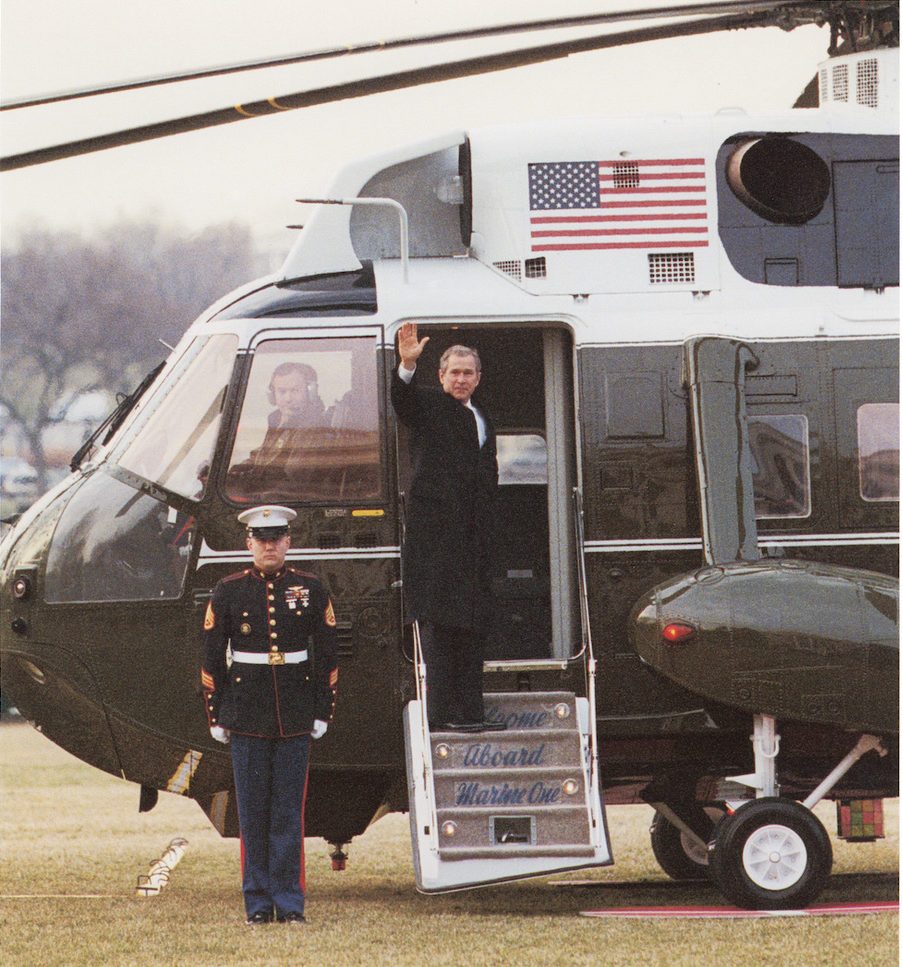

The most obvious thing to do in this situation was to go to the source of power itself, so in 2005, when I was in second grade, I wrote a letter to President George W. Bush with a simple message about the war in Iraq: “I disagree with the war. It’s not right for people to get killed. Do something about it.” He (or most likely a White House intern) responded with a letter that outlined the humanitarian missions in the country and provided a somewhat bright outlook for the future of democracy in Iraq. As a bonus, I also received a photo of the president smiling and waving as he stepped onto Marine One.

I found it difficult to square that fairly optimistic letter from the president with the images and articles that appeared in the news. Bush wrote about building roads and schools for the Iraqi people, but instead I saw images of the aftermath of car bombs — craters left in those same roads and shrapnel scattered all around. He wrote about giving food, water, and medicine to those in need, but instead I watched the number of lives lost, both American and Iraqi, move steadily upwards.

The dissonance between the efforts outlined in the letter and the reality playing out in the world left me confused. As I got older, I tried to find some clarity about the wars that hummed in the background of my childhood. I read books, like The Forever War by Dexter Filkins and The Looming Tower by Lawrence Wright, about the lead-up to 9/11 and the history of the countries we invaded as a result. I asked my parents questions to see if maybe they could elucidate the meaning of these wars.

In part, this confusion stemmed from the name of the war as a whole — the Global War on Terror. What did it mean to be at war with terror? When we learned about the wars of the past in school, they always seemed much more straightforward. There was a clear enemy — the British, the Germans, the Austro-Hungarians, the Vietcong, ourselves — and the battle lines were more obvious. But to be at war with an emotion? It didn’t make sense. I certainly understood that 9/11 was terrifying; it terrified me when I was old enough to learn more about it. But there’s so much terror in the world, including terror enacted by our own country. How can we possibly fight it all?

Well, we can’t.

That’s become painfully obvious, especially recently as we’ve watched the United States withdraw from Afghanistan, effectively ending the war during which my generation came of age. September 1, 2021, was the first day of my conscious life when the United States was not at war. Over the next several years my generation — the one that doesn’t remember 9/11 — needs to unlearn the status quo of the last two decades. Being at war is not normal, and nor should it be. Despite 20 years of sacrifice and suffering, terror, in all its forms, continues to rear its ugly head — this past year has been a difficult reminder that no matter how many tools or technologies we have at our disposal, we can’t rid the world of fear and terror.

Back in 2014, I went to the 9/11 Memorial and Museum while on a college-visit spree along the East Coast. I had just finished a two-week high school course at Georgetown on international relations and national security. That summer, the Islamic State rampaged across Iraq and Syria, terrorizing the people who lived there. The visit to Ground Zero felt more relevant than ever. One room in the museum played the phone calls passengers made from the planes to family members and loved ones. While listening to these desperate voices, my tears finally came, and the terror of 9/11, of what it stood for and precipitated, finally became real to me.

As we left, we passed the gift shop, where the words “Never Forget” were emblazoned on T-shirts, posters, mugs, keychains, and any other touristy item you can think of. What does it mean, though, when you can’t remember the very thing you should never forget?

Emma Swislow is the editorial assistant at the Center for a New American Security.

“The Long Tunnel” is a series of articles reflecting on the impact of September 11 and how it has shaped the world we live in today. You can read more in the series here.