This month’s installment of Inkstick’s new monthly culture column, The Mixed-up Files of Inkstick Media (inspired by From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler),where we link pop culture to national security and foreign policy, is all about one of the columnist’s biggest passions: Anime.

Okay, I admit it: I’m an otaku.

If you don’t know what that term means then you’re lucky, but for the sake of public education, it’s a somewhat derogatory term used to describe mega-fans of Japanese comics and animated TV series or movies referred to as manga and anime respectively. If you’ve been unfortunate enough to follow me on Twitter prior to June of this year, you’ve probably seen anime spam I post on main, but fear not, for I’ve officially moved all cringe-worthy “Haikyuu”-fangirl content to a separate account now. Why am I bringing this up though? Because what better way to contribute to a brand-new column on Inkstick meant to explore the connections between random and fun (or sometimes serious) pop culture phenomena or icons with nuclear weapons and national security than with a brief glance at the medium that’s defined over half of my life so far?

As much as I want to write a full 50-page thesis discussing the manifestations of the influence of the nuclear weapons age in Japanese anime, I’ll spare you with a superficial history of how Japanese anime got started, a brief look into a handful of titles, and shout-outs to the vanguards of the Harajuku aesthetic and fellows protestors who skip class to read manga and watch anime (myself not included in the skipping class part though *winkwink*).

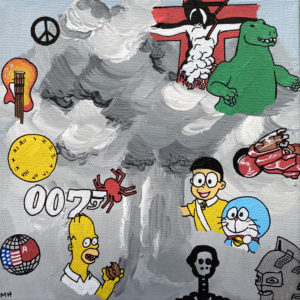

Let’s start with the basics, of course: Anime. Western animation first appeared in Japan in 1909, and the appearance of the first Japanese-made animation followed closely behind, in 1915. As a field and art form, however, Japanese-made animation didn’t really take off until the post-war period, and influence from that period of time still reverberates throughout the entire culture of anime to this day. References to and inspiration from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be found throughout all of the last 75+ years of animated series and movies coming out of Japan, from “Astro Boy,” “Ultraman” and “Ultraseven,” “Doraemon,” “Time Bokan,” “Akira,” “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” “Code Geass,” to “Attack on Titan,” just to name a few. Mushroom clouds appear in just about every episode of “Time Bokan,” for example, as the villains blast off into the sky after defeat (think Team Rocket from “Pokémon”).

Our relationship with Japan in the modern day is heavily influenced by our consumption of their media, which in turn is heavily colored by the history of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and military occupation following the end of WWII.

“Astro Boy” is the first anime to have achieved mass popularity and depicts a young robot boy fighting bad guys. Simplistic though its general plot may be, the show also represents what became a common theme in all of anime: Humans vs. technology, or modernization vs. the maintenance of tradition. Morally, the themes explored in anime evolved in complexity with the debut of “Ultraseven” of the “Ultraman” trilogy. The show took what had been the standard black-and-white portrayal of good versus evil in shounen (young boys) anime series and turned it all gray. Villains were no longer straightforward monsters. Instead, they were complex and capable of greater thought and reasoning. The shift in narrative displayed in “Ultraseven” can be attributed to the trilogy’s lead writer Tetsuo Kinjo who grew up in Okinawa, which was under heavy US military control when he was growing up. Okinawans lived in limbo. They were not truly Japanese but were not American either. Kinjo questioned what peace really meant when living under occupation and why the lives of people who have hurt others should be defended.

Time-skip to 1988 to the airing of one of anime’s most seminal works: “Akira.” The movie takes place in Neo (“New”) Tokyo 31 years after World War III, during which a new bomb had been invented and exploded over Tokyo. This premise depicts the potential consequences of another nuclear-like disaster. While real-world Tokyo, and Japan as a whole, exploded into a thriving metropolis within mere decades of the war, the Neo Tokyo of “Akira” was reduced once more to rubble by the turn of the century. “Old Tokyo” refers to the site of impact and its surrounding areas. The site is heavily associated with death and destruction, marked by the massive and eerie crater left behind.

The release of “Akira” can be historically linked to what is approximately the height of Japan’s economic boom and sudden ascension in world influence/positionality. As an emerging power, the story of “Akira” could be interpreted as a reflection of Japanese ambivalence to its rise in power. Testuo’s final metamorphosis represents an enjoyment in the newly gained powers combined with fear and uneasiness for what comes next.

“Akira” is thus a perfect example of the common treatment and use of the mecha genre in anime, one that showcases the power and destruction that comes with technology and weaponry too advanced for human reasoning and morals to keep up with.

Okay, so now what? It might seem obvious that a historic event as significant as being nuked would leave some kind of impact on a place’s culture and media, but the effects stretch far beyond the borders of Japan, especially given the massive explosion in popularity of manga and anime in mainstream American and worldwide culture today. When I was in middle school and high school just ten years ago, you were considered a loser for watching “Naruto” because it’s weird. Now, you’re a loser for watching “Naruto” because it’s too mainstream.

Storytelling in manga and anime go beyond the pages and screen, too. Layers of different stories can be simultaneously explored in these mediums. They’ve played significant roles in the development and spread of protest and social justice movements, such as from the origins of “kawaii culture” (“kawaii” being Japanese for cute). For example, Harajuku Lolita originally served as an emblem for the rejection of traditional values and patriarchal society, while Hello Kitty served as an extension of Japanese soft power, depicting Japan and Japanese people as almost “placated” and “de-fanged” relative to pre-WWII.

In post-war Japan, a popular form of protest against the oppressive and elitist academic and societal standards of the time was to skip class and read manga instead. Certain manga characters were even used as mascots for various student protest groups and could even serve as identifiers for which factions they belonged to. And, what kinds of manga were they reading? Shounen series were particularly popular such as “Tomorrow’s Joe,” “Star of the Giants,” and “Ninja Combat Manual” — stories that centered the youth of the day fighting oppressive systems. For the most part, the politics within manga have flown relatively under the radar, but that’s not to say themes this form of media explores go unnoticed. In 2013, city officials in Matsuda banned the manga “Barefoot Gen” by Keiji Nakazawa, an atomic bomb survivor who fictionalized his experience of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima along with heavy criticism for the Japanese imperial army in graphic detail.

Manga and anime continue to grow as a worldwide phenomena, with manga sales dominating the comic books bestseller lists to the point you would wonder if Marvel and DC comics are even included in the calculations. From a US perspective, our relationship with Japan in the modern day is heavily influenced by, if not entirely driven by, our consumption of their media, which in turn is heavily colored by the history of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and military occupation following the end of WWII. It’s easy to think that the content coming out of Japanese studios are just cute animations, but look a little bit deeper at the stories Japanese creators are telling and you might be surprised by the level of substance lurking beneath schoolgirl uniforms and shuriken.

Of course, like any media, anime and manga are more often caricatures of Japanese life and culture rather than a one-to-one documentary of reality, but also like any art form, they serve as modes of creative expression for anxieties, local or global, meant ultimately to foster connection and understanding. So, give an anime like “Neon Genesis Evangelion” a shot; it’s on Netflix now after all. Then, share with me what connections and understanding you gain from the story. Fair warning though: Countless essays and YouTube videos have been made in an attempt to explain the endings of both “Akira” and “Evangelion,” with little satisfaction found among the fan base. If you’re looking for something a little lighter to begin your otaku awakening with, then I’d be more than happy to spread a little bit of my anime-evangelism your way.