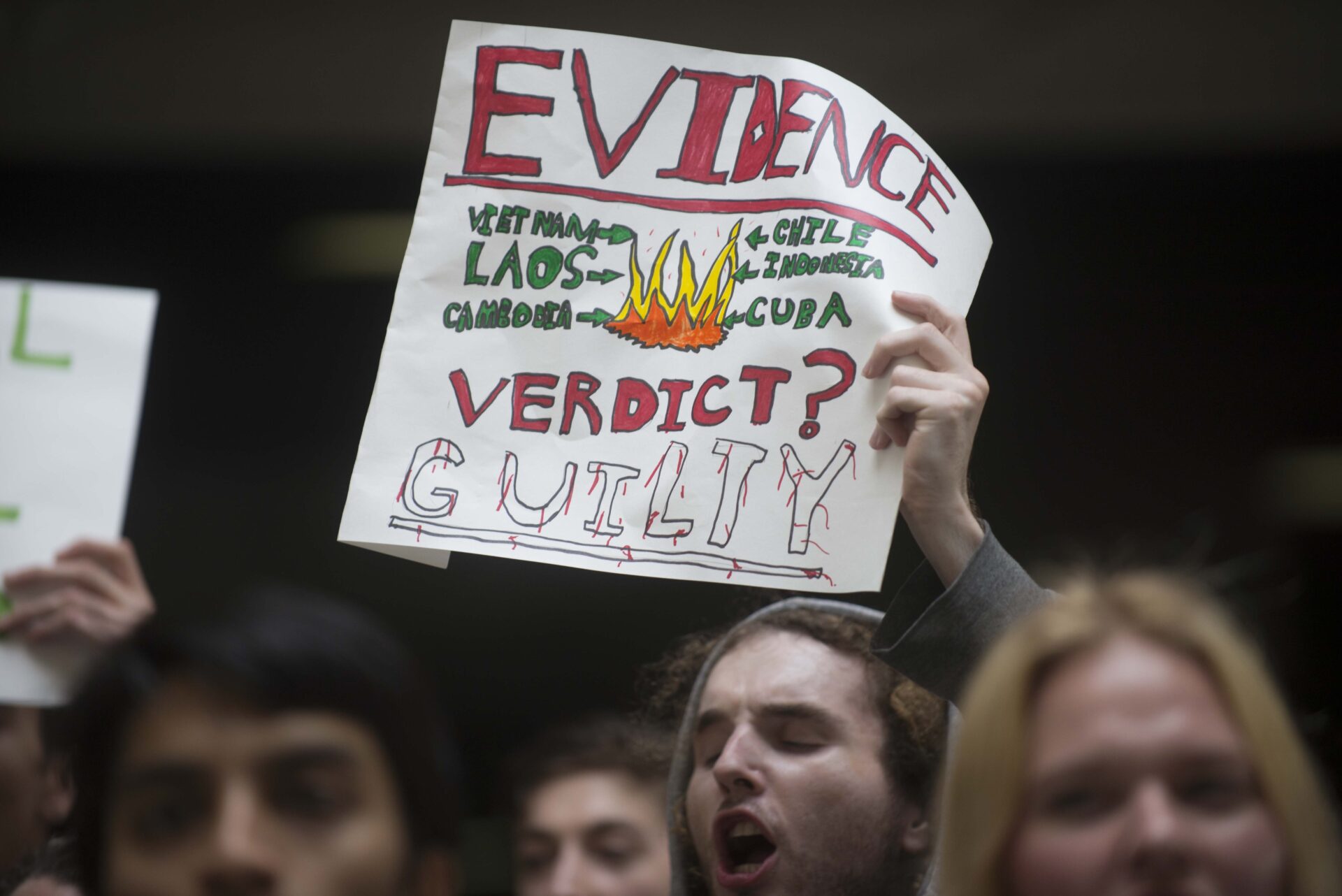

Former national security adviser, secretary of state and Nobel Peace Prize winner Henry Kissinger, who died last week, was responsible for the killing of between three million and four million people across the world between 1969 and 1976, according to historian Greg Grandin.

“I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people,” Kissinger, then US National Security Adviser, told the 40 Committee on June 27, 1970, referring to the upcoming Chilean presidential elections at the time.

Eleven years earlier, on Jan. 1, 1959, the revolutionaries of the July 26 guerilla movement entered Havana, Cuba, having overthrown the US-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. The Cuban revolution commenced with a guerilla attack on the Moncada Barracks on July 26, 1953, and became the catalyst for social change in Latin America, as well as a major preoccupation for the US, which lost a foothold in the region.

While breaking off relations with Cuba and other Latin American countries, US President John F. Kennedy launched the Alliance For Progress in March 1961 — a 10-year plan that sought to undermine communist influence in Latin America through economic cooperation between the US and the region. The $20 billion allocated for the program included a budget for backing military coups.

In May of the same year, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) launched the Bay of Pigs invasion against Cuba, an operation that had been approved by President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration in March 1960. The operation involved the training of a paramilitary group composed mostly of Cuban dissidents, to topple Fidel Castro’s government. The primary US preoccupation with Latin America during the Cold War was to counter the Cuban revolution’s influence.

Yet, the focus would swiftly shift to Chile, where the Popular Unity coalition led by Salvador Allende was gaining traction and rousing fears in the US that socialism and communism could make inroads not only through guerilla revolutions but also by way of democratic elections.

Allende’s Popular Unity manifesto addressed the country’s socioeconomic crisis that was exacerbated by the US’s capitalist ventures. The coalition won the elections that same year in September, triggering the next phase of Chile’s destabilization which culminated in the US-backed right-wing Augusto Pinochet dictatorship that lasted from 1973 until 1990.

By the time Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, Chileans were grappling with their country having become a US laboratory for neoliberal politics.

The 40 Committee

The CIA was founded on Sept. 18, 1947, by US President Harry Truman. In 1948, the 40 Committee was informally established, going by several different names until the presidencies of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Operating in utmost secrecy, the five-member 40 Committee was the best example of plausible deniability in US politics. While it is assumed that CIA operations require presidential approval, the absence of substantiating such a claim allows the president to claim denial of any covert operations, should they become public knowledge.

Such detail was laid out in a letter Nixon wrote in 1970: “By covert action operations I mean those activities which, although designed to further official U.S. programs and policies abroad, are so planned and executed that the hand of the U.S. Government is not apparent to unauthorized persons.” One major example of plausible deniability is the extrajudicial killing of Argentine revolutionary Ernesto Che Guevara in Bolivia.

Kissinger, who was the Chairman of the 40 Committee during the presidencies of Nixon and Ford, leaves behind a macabre legacy of backing right-wing dictatorships that terrorized, tortured, murdered and disappeared thousands of civilians in Latin America. It was through the 40 Committee that Kissinger worked to thwart Allende’s electoral victory, later destabilizing his government through Pinochet’s military coup.

In September 1974, a New York Magazine article described Kissinger’s role in the 40 Committee in relation to Chile: “Action against Allende between 1970 and 1973 was one of Kissinger’s high priority projects. He personally assumed control of the C.I.A’s covert moves through the 40 Committee, and of a parallel economic and financial blockade working through an interdepartmental task force.” For Kissinger, the article continues, Chile was an experiment to see if the US could destabilize governments through covert action, instead of using military force. Through the 40 Committee, Kissinger authorized the release of funds to the CIA for overt actions against Allende.

Kissinger’s Role in Chile

Declassified documents published by the National Security Archive illustrate the extent of Kissinger’s involvement in Chile, including at times disregarding diplomatic advice.

A memorandum for Kissinger’s attention by Viron P. Vaky, who served as US ambassador to Costa Rica and Colombia under Nixon, warned against US involvement in Chile, stating that exposure of covert action would be disastrous for US foreign policy, also noting that any Marxist victory in Latin America as a result of Allende’s electoral triumph could be contained.

The first attempt at a military coup against Allende was orchestrated by the CIA prior to Allende’s inauguration in 1970. The intent was to kidnap General Rene Schnieder — who had openly declared in the right-wing Chilean newspaper El Mercurio that the Chilean military would not intervene in the outcome of the country’s elections — and blame the kidnapping on Allende’s supporters.

Declassified documents on the matter from the CIA after a meeting with Kissinger illustrate this point: “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup… It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG [US government] and American hand be well hidden.” Schnieder was assassinated by the CIA, and Kissinger’s involvement in the planning was used by Schnieder’s family in legal proceedings against Kissinger.

I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.

– Henry Kissinger

Another of Kissinger’s attributes exposed in the declassified documents is his disregard of human rights. In a 1975 declassified document, Kissinger ridicules human rights despite the crimes against humanity committed by the Pinochet dictatorship. “I read the Briefing Paper for the meeting and it was nothing but Human Rights,” he said. “The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there were not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

In 1976, as pressure increased on Chile, even within the US, for the dictatorship to pay more attention to human rights, Kissinger told Pinochet, “You did a great service to the West by overthrowing Allende.”

Murdered Leftists

In 1971, the 40 Committee was involved in backing another military coup, this time in Bolivia. Once again utilizing the same premise of increasing left-wing presence in the region, the committee approved covert funding to topple Bolivian President Juan Jose Torres, despite the fact that Torres, when he was serving as Chief of Staff of Bolivia’s Armed Forces, had been involved in the plans to kill Che Guevara on Oct. 9, 1967.

The CIA was also cautious about Cuba’s take on the US-backed coup that ousted Torres. A declassified document relays Cuban Foreign Minister Raul Roa’s concerns that the Bolivian coup was orchestrated with “backing from the United States, Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina.”

The document also notes Cuban concerns as expressed in the island’s national newspaper, Granma, that the US was seeking “to isolate Cuba, Chile, and Peru, and to discourage peoples which, as in Uruguay, are seriously threatening to sweep the representatives of oligarchy and imperialism from power.”

In Uruguay, through Kissinger, the US enlisted Brazil and Argentina’s help in thwarting the electoral result.

When Jorge Rafael Videl came to power in Argentina through another US-backed military coup in 1976, Chile’s example was emulated, including the disappearances of political opponents through the death flights. As early as June 1976, Kissinger told the then Foreign Minister Admiral Cesar Augusto Guzzetti, “If there are things that have to be done, you should do them quickly. But you should get back quickly to normal procedures.”

In 1975, with the aid of the CIA, Pinochet launched Operation Condor — an intelligence operation that included the participation of the Latin American dictatorships of Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay. The operation targeted left-wing individuals and organizations, leaving behind a deadly trail of between 60,000 and 80,000 murdered leftists, as well as some 400,000 political prisoners in Latin America.

Declassified documents have also revealed that Kissinger could have prevented the murder of Chilean diplomat and economist Orlando Letelier. The day after sending a memo instructing ambassadors to pursue no deterrence against Operation Condor plots, Letelier was murdered in 1976 in Washington by a double agent for the CIA and Chile’s National Intelligence Directorate Michael Townley.

Under President Ronald Reagan, Kissinger was appointed Chairman of the National Bipartisan Commission on Central America, which was established by Executive Order 12433 on July 19, 1983. The Committee was tasked with providing advice on how to best “respond to the challenges of social, economic, and democratic development in the region, and to internal and external threats to its security and stability.” In December 1982, for example, the Guatemalan government of General Efrain Rios Montt described itself as deserving of US military aid, despite reports by Amnesty International of the killing of over 2,600 people at the hands of the security forces since March of the same year. In 1983, aid to Guatemala was restored.

All the covert action Kissinger and the CIA instigated against Cuba, and for reasons pertaining to the Cuban revolution, failed to bring down socialism on the island, and its internationalist approach. In Africa, in particular, Fidel Castro supported the anti-colonial struggles taking place in the 1960s and 1970s, leading the US to even consider airstrikes on Cuba.

“I think sooner or later we have to crack the Cubans… If they move into Namibia or Rhodesia, I would be in favor of clobbering them,” Kissinger told President Ford in March 1976. In a later conversation that same month, Kissinger further elaborated: “If we decide to use military power it must succeed. There should be no halfway measures — we would get no award for using military power in moderation.”

From one single premise — that of preventing the Cuban revolution from gaining more regional and global influence against US imperialism — Kissinger created a bloody career spanning decades of foreign intervention. His death spelled the end of an era. The legacy of that era, however, has not only resulted in secrecy over the locations of Latin America’s disappeared, but also the dilution of left-wing politics in the region as governments grapple with historical memory now tainted with the almost normalized neoliberal policies that first wreaked havoc in Chile.