When a military veteran and mother of three was job hunting in Southern California about a decade ago, a friend of her mother’s who worked at a defense contractor offered to send her résumé around, setting her on a path that led to hourly jobs on the floors of two of the United States’ largest weapons makers, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. The industry seemed like a fit for her. She was an Air Force reservist and her grandmother had been one of the iconic “Rosie the Riveters” who manned the weapons plants that supplied the US war effort during World War II.

But both the nature of the work — refurbishing B-2 bombers and building aircraft parts in the US Air Force Plant 42 in the Mojave desert outside Los Angeles — and her discomfort with the predominantly male workforce made her eager to leave. As a single mom with childcare obligations, she felt unwelcome in workplaces she characterized as having a “male party mentality” and where she said women’s career advancement was stymied for not being “buddy buddy” with male coworkers. Anyone outside that fraternity was “miserable,” she said. The work also took a toll on her home life. The weekends, night shifts and changing schedules to meet military production deadlines led her oldest daughter to later complain that she had missed out on years of her youth when she needed to take care of her younger siblings.

The veteran and mother rattled off the reasons why women who could find a better job would avoid the one she took: “It’s really long hours on your feet. Bending, stretching, lifting. Being in, depending on the job, possibly in some really uncomfortable, bent-up positions for hours on end. The chemical exposure.” The hourly worker asked Inkstick not to use her name as she spoke critically about her former employers. “A lot of women don’t want to have to do that work. It’s hard work. They can get a job that’s a lot easier and doesn’t do damage to your body.”

Higher Budgets, Fewer Jobs

Pentagon budget season began in March, when the Department of Defense published its 2024 funding request, $842 billion — the highest amount since World War II, save for a peak moment of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. If trends from recent years continue, around a hundred billion will likely go to the five largest military contractors that dominate weapons projects, such as those the hourly employee in Southern California worked on. Congress is also expected to add tens of billions of additional spending beyond even what the Pentagon asked for, seeking to channel funds to and create jobs in their districts. But employment in the private defense industry has plummeted in recent decades — from an estimated 3.2 million jobs in 1985 to 1.1 million in 2019, according to the National Defense Industrial Association. And the positions that remain don’t get spread evenly among Congress’ job-seeking constituents, such as women workers.

In 1976, Lockheed Martin’s workforce was 16% female; in 2022, that number was 23%. This wasn’t because women were staying home.

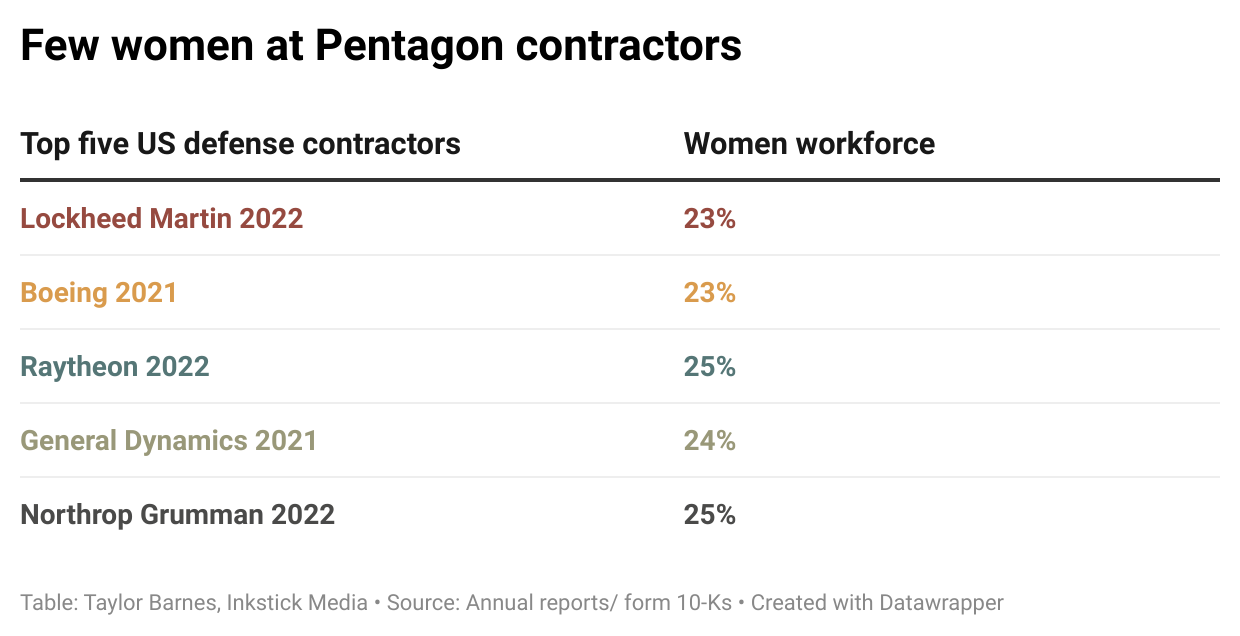

The Bureau of Labor Statistics describes women’s rapid entry in the workforce as “a major development in the labor market during the second half of the 20th century.” Women now make up 46.8% of the US labor force. But none of the top five defense contractors (see chart) have a workforce that’s more than a quarter female.

Inkstick reviewed decades of corporate annual reports, documents that give investors an overview of companies’ business and financial conditions that are available online and through a historical database called the Mergent Archives. Those reports offered periodic glimpses of women’s employment at major defense contractors; at Lockheed Martin, for example, women’s employment rates have budged little over nearly half a century. In 1976, Lockheed Martin’s workforce was 16% female; in 2022, that number was 23%.

This wasn’t because women were staying home. Women’s participation in the workforce shot up alongside the feminist movement and the increasing need for families to earn two wages, said Ileen DeVault, a labor history professor at Cornell University. But they largely ended up in what she called stereotypically female jobs, such as nursing, elementary education, clerical office jobs and restaurants.

“They’re not earning the wages that any sort of heavy industrial manufacturing workers [do] — whether that’s auto, steel, Lockheed Martin,” she said, “The wages, even when they unionized, are not going to be as high as they are in those male-dominated occupations.”

DeVault pointed out that in the construction industry, a field that, like military production, often provides high-paying, blue-collar union jobs, the government has a quota for women’s employment on federally funded construction projects. (The quota isn’t high — it’s just 6.9%.) That rule is a result of a lawsuit from the National Women’s Law Center in 1976. And in March 2023, the Biden administration announced that semiconductor companies seeking subsidies under the CHIPS act will need to provide childcare for employees, a policy that could alleviate workforce shortages by enabling more women to enter that labor pool. But no such affirmative action or childcare requirement exists for Pentagon contractors.

Ashley Shaffer, a former Lockheed Martin engineer, said a quota policy “would be nice,” but that it also may force women into jobs that just don’t work for them, like manufacturing roles with inflexible schedules at odds with childcare duties.

Shaffer spent a decade with Lockheed Martin after earning an industrial engineering degree in 2004 from Georgia Tech. As a project manager at an aircraft plant in the Atlanta suburb of Marietta, she made sure the production lines ran smoothly. Over the years she rotated into different roles involving business development and scheduling.

Barriers to Longevity

One of the reasons demographics were so skewed at her workplace, she said, is because the military, whose active-duty force is itself 82% male, was a pipeline into the company. She also said there were things women like herself just preferred not to put up with, like getting catcalled when walking across the floor. For her, the impetus to leave mostly had to do with professional stagnancy. She saw little opportunity to advance in a place where employees often spent decades at the company, meaning she’d have to wait for someone to retire before she could take their role. She left Lockheed to take a job with Atlanta’s mass transit authority, MARTA, working on technology related to security cameras and controls that allowed employees to access restricted areas.

“I want to continue learning,” Shaffer said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s an airplane being built or software being built or something else.”

Electrical engineer Karen Hsu, on the other hand, turns down offers from headhunters and tells them she’s happy at Boeing in Arizona, where she’s worked for nearly 20 years on military helicopters like the Chinook and Apache. She’s currently the only woman among the 35 to 40 people she works with in her flight test group, which involves getting in awkward positions as she troubleshoots electrical wiring, and eventually jumping off the aircraft as its rotors start. (That physically taxing work would be difficult with a pregnant belly, she said, though Hsu had her three children while working an office job at the company.)

Her workdays sometimes start as early as 3 am when she preflights aircraft for sunrise tests. Maintaining that schedule as a single parent, she said, would involve shelling out money for a nanny if she didn’t have her own mother available to take the kids to school.

Hsu thinks the number of women at contractors like Boeing may trend upward without an employment quota as more women enter STEM fields, a marked shift from her time. “I’m pretty sure I knew the same five women in my classes,” she joked.

Women nowadays outnumber men in the college-educated workforce, including in STEM fields, of which women represented 53% of degree-earners in 2018, according to the Pew Research Center. But their studies and employment are heavily slanted toward healthcare, according to Pew, rather than engineering or computer science.

As her engineering career veered into different directions since entering the labor market in 1970, Patricia DuRant has also seen the gender makeup of her coworkers shift, and nowadays gets to watch where the women filling her generations’ shoes choose to take their labor.

She was the only woman to graduate with a physics degree in her class at Georgia Tech, after which she earned a masters in materials engineering. She went on to work at AiResearch, a military contractor in Arizona that repaired aircraft parts, though she said her work became more geared toward the civilian market as the Vietnam War came to a close. She was the only woman among about 50 engineers she worked with. She got along well with the male machinists, one of whom brought her a grilled javelina leg as a token of appreciation for helping him with a stubborn titanium part. Still, she took her lunches with the CEO’s secretary, a woman who would have otherwise been sitting alone among the crowds of men in the cafeteria.

Later in her career, she was pleasantly surprised to be recruited to teach at the environmental engineering department at Cal Poly Humboldt in northern California. Her students there were up to 40% female, she said, and a similar proportion of the tenured professors were as well. Her graduates go into a variety of fields, she said, including construction and civil engineering.

“When you’re young and you have a science inclination, you’re good at math [and] you start looking at what’s available out there, on the surface, some of the engineering areas just aren’t that appealing to women,” DuRant said. Many of her environmental engineering graduates enjoy the nature of their work, telling her that it takes them outdoors to do things like stream tests and measuring air pollution.

“A lot of it is a lot more appealing, I think, to women, than this sort of traditional hardcore engineering, although I wouldn’t say environmental engineering is watered down in any way. It’s modern,” she said. Women appreciate the youthfulness of the sector, she added. “They don’t have to deal with the old guard.”

Inkstick Media contacted spokespeople from Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman about the workplace allegations made by the hourly worker in Southern California; neither commented on whether they had policies to address favoritism or related pay inequities. A spokesperson for Lockheed Martin said that the company “create[s] pathways for diverse talent and increase[s] gender representation by partnering with universities and social impact groups, strengthening STEM pipelines, and ensuring we continue to recruit our future workforce inclusively and equitably.”

The hourly worker told Inkstick her time at the two companies was “awful” and that she has left the industry.

“I was thankful for having a job because as a single mom, I needed to take care of my kids,” she said. “But I’m really happy I’m not in it anymore.”