I had intended to stay offline during the 2023 Nigerian election.

Journalism had taught me early on how misleading and emotionally overwhelming social media can be during such moments. Moreover, I had lived through the EndSARS protests, which made jarringly clear the mental toll of constant social media consumption during major political events.

I had been online in the days leading up to the election, stalking conversations, researching candidates, and positioning myself somehow in that awkward journalistic stance where we condemn the evil we witness as if it were separate from us, and from the politicians that foment the social chaos.

I texted close friends early on that I would be offline for most of the day. I stayed away from reporting on the election and avoided having public conversations about it. On election day, I simply wanted to vote, read, and stay away from the internet.

Alas, my best-laid plans were quickly waylaid. Information is sight, and we have built an information ecosystem that is heavily reliant on being online. Being disconnected can feel like darkness.

By 10 am, I was back online, telling everyone that videos circulating claiming that Peter Obi of the Labour Party was dropping out of the presidential race for Abubakar Atiku of the People’s Democratic Party were false, that people without voter cards cannot vote, and that bank transactions were not frozen due to the election.

Until then, I had been pretty optimistic about the elections.

Disinformation in the days leading up to the election had gained very little traction. But then on election day, I spent more than thirty minutes convincing a food vendor that the wire transfer I had made and that had been reflected in her bank account was real because just the day before, false information had circulated widely that banking tech infrastructure would be disabled on election day.

What had changed?

DEEP FAKES AND MEDIA LITERACY

To answer this question, I first reached out to Phillip Anjorin, a fact-checker with one of West Africa’s leading fact-checking platforms, Dubawa. The night before the election, I had sent him the video of Peter Obi supposedly conceding to Atiku Abubakar, assuming it was a deep-fake. He confirmed and clarified that it was, in fact, an old video shot when Peter Obi was still with the People’s Democratic Party in 2019.

DISINFORMATION TRAVELS FASTER AMONG EVERYDAY PEOPLE WHO ARE BARELY ON SOCIAL MEDIA. MANY FIND IT BETTER TO BELIEVE THAT INFORMATION IS TRUE AND FIND OUT IT’S FALSE THAN TO THINK THAT INFORMATION IS FALSE AND FIND OUT IT’S TRUE.

According to Phillip, one of the pressing problems in fighting disinformation in Nigeria is that the grassroots are still very vulnerable. “Despite efforts by fact-checking organizations to spread media literacy, the grassroots are not yet enlightened enough on information verification,” Phillip told me. Disinformation travels faster among everyday people who are barely on social media. Consequently, it’s also harder for this set of people to receive debunks or nuanced communications. As a rule of thumb, many find it better to believe that information is true and find out it’s false than to think that information is false and find out it’s true. For a food vendor making a living on transfers of 700 naira per plate ($1.5), it’s better to be safe than sorry.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND ELECTIONS

Technology has played an incredible part in the just-concluded elections. It served as a means for young Nigerians to gather ideas, have conversations, and get live updates on the election. But with increased use of social media comes an increase in the possibility of it being used maliciously. “Ever since the EndSARS protests, social media has been recognized as a game-changer in shaping ideologies and political opinions, and a lot of bad actors were utilizing that,” said Phillip.

“Social media was a double-edged sword. On one hand, we saw a lot of participation, but on the other hand, there was also a lot of disinformation from that participation,” said Abideen Olasupo, founder of Fact-Check Elections, Nigeria.

Unfortunately, according to experts, social media moderation plunged in the days leading up to the election. Part of Elon Musk’s restructuring of Twitter included a layoff that reportedly affected all but one remaining member of the African team, allowing false information concerning the continent and especially the Nigerian elections to thrive unchecked on the platform.

Similarly, in the months leading up to the election, reports about how Facebook and Instagram were a hotbed for false information during elections and major political events in other African countries raised questions about how effective moderation was on the company’s platforms.

To fill the gap in social media moderation, fact-checkers and debunkers worked in overdrive. Years of experience had prepared Nigeria’s fact-checkers for events like this. The Nigerian Fact-Checkers Coalition was fast and decisive in debunking and calling out false information. But debunking is only one part of fighting false information, according to David Ajikobi, Nigeria editor for Africa Check. “We focus a lot on debunking, which is very important, but it is still a small part of everything.”

Much of the false information was quick to reach offline people — but not its debunking, which was a major problem. Nigeria’s election had been complicated by fuel scarcity and a badly executed, poorly communicated cash swap that greatly complicated electoral disinformation. Like the vendor who believed that wire transfers had been halted during the elections, older, offline Nigerians were deeply exposed to disinformation around these peripheral issues that, in the end, served the purpose of either swaying political opinion, creating panic, or disenfranchising voters.

“Poor communication creates a perfect ground for false information,” David said. “The government has poorly communicated many of its policies, making it easy for false information to thrive around those policies.”

THE HUMAN TOLL OF DISINFORMATION

In the lead-up to the gubernatorial elections, narratives that played heavily on tribal differences were rife, escalating ethnic tensions. False information that claimed that members of the Igbo community planned to annex Lagos state if Nigeria were to split were peddled and shared widely, especially on encrypted platforms like WhatsApp.

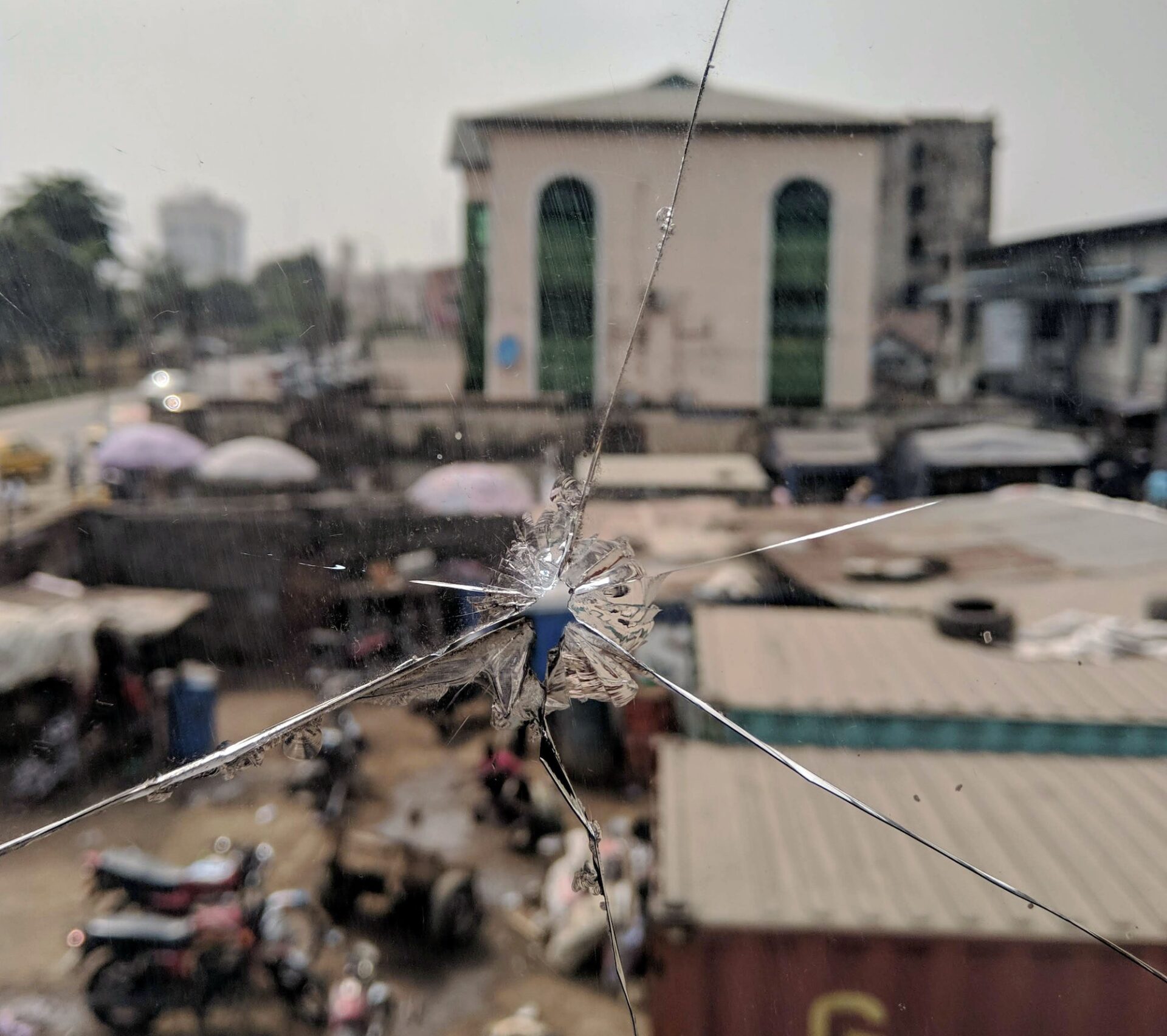

On election days, the real costs of disinformation were made blatantly clear. Disinformation soared and online conversations targeted Igbo people in Lagos, which led to violence that left many hurt and disenfranchised and at least one person killed.

The machines that drive that disinformation, meanwhile — social media companies, political leaders, and uncommunicative government commissions – continued as usual, seemingly impervious to the human toll of their ambitions.